Russian President Vladimir Putin made a lot of big spending promises in his state of the nation speech on March 1 but said almost nothing about how the Kremlin will pay for them. That means there are very likely some "nasty surprises' in store for Russians in Putin’s last term, says BSC Global Markets chief economist Vladimir Tikhomirov in the second part of a two-part podcast with bne IntelliNews, “The cost of reform – boosting incomes in the time of austerity.”

Russian President Vladimir Putin made a lot of big spending promises in his state of the nation speech on March 1 but said almost nothing about how the Kremlin will pay for them. That means there are very likely some "nasty surprises' in store for Russians in Putin’s last term, says BSC Global Markets chief economist Vladimir Tikhomirov in the second part of a two-part podcast with bne IntelliNews, “The cost of reform – boosting incomes in the time of austerity.”

The clues in the speech suggest strongly that the government is going to go over its social obligations and start tailoring them so the rich pay more to support the less well off. Income inequality in Russia remains very high, and there is no other way to foot the bill other than to cut some privileges and maybe increase taxes. That will hold down income growth and consumption, and hence Russia’s economic growth.

The giveaway was the Kremlin’s decision not to boost wages in the run-up to this election. In 2008, pensioners received a huge one-time 40% increase that lifted incomes across the board. That was also a presidential election year, but this time round the Kremlin limited itself to a few one-off payments in specific regions to deal with specific issues. “If the government were planning to lift wages across the board in the next six years it would have done it before the elections, not afterwards,” says Tikhomirov.

“There is a new deal. If you want a higher salary then you have to work harder and be more efficient,” he adds.

Putin’s speech was about going back to prosperity, and while the crisis has hurt incomes, which halved in the last eight years, more recently the bounce back has been very dramatic, with average incomes in dollar terms making back almost all of what they lost during the crisis years.

“If you look at the history of income growth, a big driver of that was the government plan to increase salaries in the public sector. It was part of a big programme that started in 2005 when there was the so-called ‘monetisation of social payments’. The government also promised to increase wages in 2005-2010 even though 2008-2009 were rather difficult years.”

Putin stuck to his guns, and Tikhomirov points out that in 2008, just as the global crisis was starting, pensioners were awarded the biggest ever hike in pensions in the run-up to the presidential elections that saw Putin step aside in favour of Dmitry Medvedev for one term.

“That helped bring incomes to the point where they kept on growing, despite the significant fall in the ruble exchange rate and oil prices. And in return the government was not demanding anything. They were just increasing salaries for people in the public sector. They decided the starting wage 15 years ago was so low that it was hard to demand any efficiency from any employee in the public sector unless you start paying larger salaries,” says Tikhomirov, who was an economic professor at Melbourne University before eventually returning to Russia.

The income gap between the public and the private sector was becoming so huge that the Kremlin feared it would lead to social instability and protests.

“We are still not out of that situation. The official statistics show that salaries in Ingushetia, for example, are 80 to 100 times lower than in Moscow. And it is very hard for any country to survive with these sorts of huge gaps,” says Tikhomirov in a Moscow café just up the road from the Russian White House.

This strategy ended in about 2011, and since then government spending has become stretched as a result of these increases. Any further increases would automatically lead to a growing imbalance in the budget – a growing deficit, and the need to increase debt. Putin was, and is, a very strong supporter of the view that Russia should have a balanced budget and special reserves to offset any shocks, says Tikhomirov.

Putin has said several times “if you want to get higher wages you should work more efficiency. He has linked wages to productivity,” says Tikhomirov. This is an idea clearly borrowed from former finance minister and co-head of the presidential council Alexei Kudrin, who authored one of the blueprints for economic policy under consideration.

There were some salary hikes for public sector workers, like doctors and teachers, ahead of the March 18 presidential election, but Tikhomirov points out that the increases were selective, and they are not permanent.

Tikhomirov argues this is a fundamental change in the way the Kremlin views the issue of boosting salaries. The fact that the Kremlin limited its largess to a few, making targeted one-off payments as part of its election campaign, suggests this time round Putin is demanding something back from the work force — higher productivity in exchange for higher wages.

“Putin concentrated on the good things in his plan – better schools, better healthcare – but he didn't say how these goals could be reached and what is the source of funding. And this money must come from somewhere,” says Tikhomirov.

Cuts are one way to raise more money. Increasing the debt is another. But these choices come with their own economic costs and Putin has said nothing on the topic.

“My view is the government is likely to take a fairly unpopular position on how these big goals will be funded,” says Tikhomirov in the podcast. “That includes an increase in the retirement age, which seems to be a done deal. That could lead to an income tax increase from 13% to 15%-16%. Or some mild progressive tax, up to 20% — I don't have a clue and there are various options floating around. I think the government has not yet decided,” the economist says.

The government is likely to also scrutinise social benefits, including the subsidies paid on communal tariffs like electricity and gas. That would mean a basic subsidies rate, but if you consume more then you pay more. And things like child support could become means tested, as even if you earn RUB1mn a month in Russia and have three kids you get the same subsidy as someone earning RUB50,000. And the Soviet system of early pensions for workers in selected industries is also still in place, which could be dismantled. The list of cuts and savings to Soviet-era legacy benefits that could be made is long.

“There are many options but if you do any of these things then they will put more pressure on average per capita incomes,” says Tikhomirov. “So post elections there is a high probability that consumption in Russia, a driver behind growth, is not going to be growing that significantly.”

This article contains selections from the longer interview. Listen to the complete interview here.

Features

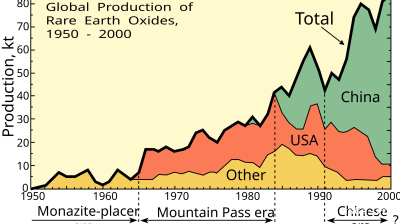

Asian economies weigh their options amid fears of over-reliance on Chinese rare-earths

Just how control over these critical minerals plays out will be a long fought battle lasting decades, and one that will increasingly define Asia’s industrial future.

BEYOND THE BOSPORUS: Espionage claims thrown at Imamoglu mean relief at dismissal of CHP court case is short-lived

Wife of Erdogan opponent mocks regime, saying it is also alleged that her husband “set Rome on fire”. Demands investigation.

Turkmenistan’s TAPI gas pipeline takes off

Turkmenistan's 1,800km TAPI gas pipeline breaks ground after 30 years with first 14km completed into Afghanistan, aiming to deliver 33bcm annually to Pakistan and India by 2027 despite geopolitical hurdles.

Looking back: Prabowo’s first year of populism, growth, and the pursuit of sovereignty

His administration, which began with a promise of pragmatic reform and continuity, has in recent months leaned heavily on populist and interventionist economic policies.