Six distinct social classes have emerged in the Czech Republic in the three decades since the Velvet Revolution of 1989, according to the large-scale Czech Radio sociological survey “Divided by Freedom” conducted in June and published in September.

The picture revealed by the survey is a complex one. It shows that everyone has different types of resources, which means that society is not so divided as some election results may show, however, it has increasingly been splitting. The Czech education system is freezing this situation rather than helping social mobility, said co-author of the study and STEM agency sociologist Martin Buchtik.

The results reveal that almost 50% of Czech society is divided into three types of lower middle class and a further one-fifth into the impoverished underclass; a sizeable middle class has also emerged, but fewer than 1% of the population fall into the “elite” category of people with high levels of capital in all measured criteria, such as economic, cultural and social capital.

This is in contrast to the results of the 2013 Great British Class Survey, upon which the Czech survey was based. According to the report, the reason this group is so small in the Czech Republic is poor consistency of capital. Not all rich people in the country have high competence, rich cultural capital and contacts.

“The post-revolutionary elite … has not been established after 30 years. In particular, it lacks the intergenerational transfer of social status, which in our country, unlike Britain, has been interrupted in every generation or at least been very difficult for the last hundred years,” said Buchtik.

According to the study, the widest group is defined as the “secured middle-class” with secured income and property. 12% of the population belong to the so called “emerging cosmopolitan elite” that has less wealth but higher potential for the future thanks to its strong social contacts, cultural capital, language and digital skills. These two prosperous classes together account for about a third of society.

Almost half of the population fall into the three types of lower middle class. This includes the “traditional working class” (14%) that works manually, has a solid income and wealth, but limited other resources such as contacts, cultural capital, and new competences.

The next category, unique to the Czech Republic, is the “class of local ties” representing 12% of the population, with below-average income but a well-established network of contacts. “This class, I believe, is also a result of society before 1989, when this sort of social capital was very important,” said co-author and sociologist Daniel Prokop. Many members of this class are from the numerous small villages in the Czech countryside.

“These people live in the Vysocina Region or parts of the Central Bohemian Region. You can’t tell whether they are rich or poor, as they have other resources rather than just income,” Prokop said.

The third and last of the lower middle classes is the “endangered class” which make up 22% of Czech society, out of which 62% are women with low incomes and almost no wealth, threatened by loss of employment. The endangered class is socially and culturally closer to a middle class but economically bleeding.

The sixth and final class at the very bottom of Czech society is the “impoverished class”, representing one-fifth of the population. Members of this group have very poor education, and no social capital or resources to improve their situation.

The members of social classes are not evenly distributed throughout the country. While in Prague more than half of the population (56%) consists of the two upper middle classes, in the Usti nad Labem Region, the majority of people are either endangered (34%) or impoverished (25%).

According to another study conducted by the Pew Research Center, presented at the Senate just recently, the overall satisfaction with life in the Czech Republic has increased over the past 30 years. Czechs appreciate that their standard of living has increased and the political environment has changed from one-party rule to pluralism.

They feel unhappy about their politicians, however, who, according to them, do not understand the worries of ordinary people. Czechs are convinced that the post-communist transformation has given more to politicians and businessmen than ordinary people, even though the transition to a market economy and a system of free competition for political parties is welcomed by the Czech society.

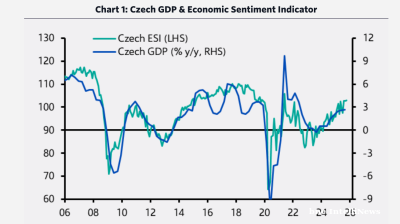

The new data was compared with historical surveys from 1991, showing that while immediately after the Velvet Revolution 23% of Czechs were generally satisfied with their lives, by 2019 the share had increased to 57%. There is also a strong link between satisfaction with life and the economic situation of the country (i.e. GDP per capita), the study said.

This article is part of bne IntelliNews’ series marking the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. Find more articles from the series here:

Corruption, racism and intolerance in Bulgaria

“I was 30” commercial stirs controversy in Romania

Central European automakers prepare for an electric future

A profound crisis of trust in democracy

Gabor Szeles, a self-made Hungarian success story

Features

_1762193126.jpg)

Is Venezuela's resource wealth Trump's real target?

As US military forces mass in the Caribbean, Venezuela's oil and mineral wealth emerges as a potential prize in a looming confrontation that will likely result in the ousting of President Nicolas Maduro.

The US now sees China as an equal - it is time for Western media to wake up and do the same

China was long filed under “too foreign, too dangerous, too different” in many Western newsrooms. Not anymore. Beijing is now impossible to ignore as American leaders have realised. Western media outlets need to wake up to this reality too.

COMMENT: China’s latest economic conquest – Central Asia

For the five Central Asian republics - Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan - China has in recent years emerged not only as a dominant trading partner, but increasingly as the only partner nearby that can actually deliver.

Slovenian consumers take energy giant GEN-I to court over price hikes

The Slovene Consumers’ Association accused GEN-I of unlawfully raising household prices at the height of the recent energy crisis.