Europe faces another energy crisis that may start in the summer leading gas and power prices to spike again. Europe won this winter’s battle in the energy war with Russian President Vladimir Putin, but despite the near to bursting gas storage tanks and unusually mild winter weather, even less gas will arrive in Europe than last year. The International Energy Agency (IEA) predicts there could be a 30bn cubic metre shortage of gas unless action is taken now.

To get through the coming winter the IEA has drawn up a five-point action plan that could avoid the worst by reducing demand, saving energy and bringing new sources of energy in a report that could more than compensate for the shortfall.

The programme calls for €100bn of investment, but it should deliver required gas savings in a single year, and the cost of the programme is far cheaper than the estimated €300bn Europe spent on relief and subsidies in the 2022/23 winter to compensate for the all-time high prices.

Moreover, keeping supply inside demand will mean lower prices for gas – a huge saving in itself – as well as a permanent reduction in gas imports that also brings huge permanent balance of payment benefits for years to come. The catch is those investments need to be made now.

The IEA conducted a stress test for the European gas balance in the winter of 2023/24, building upon the findings of the IEA report, Never Too Early to Prepare for Next Winter, published on November 3 , 2022.

“The coming year presents clear risks to energy security and affordability in Europe and beyond, as Russia continues to seek leverage by exposing consumers to higher energy bills and gas supply shortages,” the IEA said. “This report provides a menu of near-term actions and measures that can close a potential supply-demand gap in 2023 and avoid excessive pressures on European consumers and international markets.”

All told the IEA estimates that there will be a total shortfall of 57 bcm this year. Happily, the various energy saving plans, fuel switching initiatives and demand destruction already in place will cover 30 bcm of this shortfall. But that still leaves Europe 27 bcm short.

Five tools to close the gap

To avoid another energy crisis the IEA has come up with a list of five things the EU can do to reduce its need for gas or get more. The five points are not exhaustive, but the association says they are practical suggestions that will make a real difference and can be put into place now.

“We estimate that a total investment of around €100bn is required for the additional actions that close the remaining gap of 27 bcm in 2023. Around half of this is for efficiency improvements, primarily building retrofits, and 40% is for renewables. The remainder is for heat pump installations, biomethane and projects to cut flaring and methane,” the IEA said.

1. Faster improvements in energy efficiency

The first idea is to make more from less. Energy efficiency actions accelerated in 2022 as governments and consumers increasingly turned to efficiency measures as part of their responses to fuel supply disruptions. And that means using energy in buildings more efficiently.

“Most of the near-term potential for additional gas savings in the European Union lies in residential and commercial buildings. In 2022, gas demand in buildings is set to be around 25 bcm (or 17%) lower than in 2021. Most of this decline was due to milder temperatures and behavioural changes, but there were also reductions from building retrofits and other efficiency measures,” the IEA said.

The key is to renovate old buildings more quickly. Currently, around 1% of the EU’s building stock is renovated each year but with a strong policy push that could rise to 1.7% in 2023. At the same time, replacing old wasteful appliances and lighting could bring total savings to 2.5 bcm in 2023, the IEA says.

Public building renovations, energy conservation measures like turning off the lights at night and better regulation can lead the way.

“The idea of “one-stop shops” for all permits and authorisations is a practical measure that many governments have pursued to facilitate structural changes in the energy sector. These initiatives can take time to set up, and so are not necessarily a suitable vehicle to deliver rapid changes in 2023 in countries that are starting from scratch, but they can be very effective in shortening lead times for new projects and ensuring that consumers get access to the information that they need as well as assurances of the quality of service,” IEA said.

2. More rapid deployment of renewables

The move to renewables was already well under way before the war started. The energy crisis has proved to be a very effective catalyst to accelerate that transition.

Speeding up the issue of permits will be key to getting more solar and wind projects into the field in the short term, particularly by deploying e-documents in the registration and permitting process.

“Priority zones can be combined with simplified permitting procedures. Moreover, involving local administrations and other stakeholders in spatial planning can also reduce social acceptance issues over time."

Draft amendments in Poland include a proposal to increase the capacity limit for projects that don’t need building permits from 50 kW to 150 kW. Greece, Portugal and Ireland have prioritised the processing of applications for small-scale renewables by households and energy communities. There are also EU proposals to accelerate permitting for the ‘repowering’ of existing onshore wind installations if the increase in capacity does not exceed 15%.

“Our baseline expectation for 2023 is that wind and solar PV generation in the European Union will rise by more than 80 TWh compared with last year, displacing around 12 bcm of natural gas,” says the IEA. “Additional actions could result in a further 55 TWh of output from wind and solar PV (displacing a further 7.5 bcm). This will require a near-doubling of wind and solar PV annual additions in 2023 compared with our baseline expectation, a huge undertaking.”

The EU would have to triple its average deployment over the last three years of renewables to commission some 60 GW of new solar power and 25 GW of wind in 2023.

“Achieving these faster growth targets will require policy action along three main lines: reducing permitting timelines; increasing investor certainty; and promoting the integration of renewables and distributed resources," says the IEA.

But it's not an impossible task. Today the IEA says there are around 80 GW of onshore wind and 150 GW of solar PV projects at various permitting stages in the EU. While most are in the early stages, a significant share is waiting for final approval to begin construction and with some improvements can be brought across the finishing line soon.

3. Electrify heat

One-third of the European Union’s gas demand is used for heating buildings. Switching this heating to electricity and especially expanding the use of heat pumps could save another 2 bcm of gas.

Heat pumps and other electric heating can also replace gas combustion in low and medium temperature processes in industry, plus add a major improvement in efficiency: heat pumps currently on the market are three-to-five times more energy efficient than natural gas boilers.

“Our expectation is that new heat pumps will save around 1 bcm of gas in the European Union in 2023 and additional actions could save a further 2 bcm,” the IEA said. “Boosting deployment of heat pumps to the enhanced level in 2023 would lead to less than 5 TWh of additional electricity demand in 2023. Nonetheless, the gas savings far outweigh increases in gas use in the power system. Carrying out energy efficiency retrofits in parallel help reduce the size of a heat pump, minimising strain on grids, as can installing demand response-enabled devices.”

Heat pumps are expensive so grants and incentives need to be deployed. Currently 30 countries already have programmes in place representing 70% of global space heating demand that brings the upfront cost borne by consumers for a new heat pump below that of a new gas boiler. Many schemes offer additional support for low-income households, as in France and Poland, or for high-efficiency models, e.g. in Germany and Denmark.

Heat pumps have been used in industry for some time, especially in sectors with a high demand for process heating and drying. The paper, food and chemicals industries have the largest near-term opportunities, with nearly 30% of their combined heating needs able to be addressed by heat pumps.

4. Encourage behaviour changes

One of the easiest changes to implement which has an enormous effect on gas consumption is simply to encourage people to turn the thermostat down by a couple of clicks.

“We estimate that actions by consumers may have saved 3-10 bcm in 2022: these include changes in energy use motivated by higher prices as well as by behaviour. We estimate that behaviour changes – driven by regulatory interventions, awareness campaigns and prices – could help to deliver an additional 5 bcm in gas savings in 2023,” the IEA says.

The average temperature for the EU’s buildings’ heating is currently around 22°C. Reducing buildings’ heating by 1°C reduces gas demand by 10 bcm a year. Public education campaigns in the Netherlands, Belgium, Ireland and Denmark all encourage limiting space and water heating to reduce dependency on Russia while combating climate change. And other measures like encouraging showers over baths or installing smart metres to provide consumers with real-time feedback on energy use also have a big impact.

Again the policies governing public building use can lead the way. An Energy Efficiency Obligation Scheme can mandate utility companies to make energy efficiency savings across the customer base and is tailored to reduce demand at peak demand hours, when gas-fired power is most likely to be used.

The public sector can lead by example. In Germany, for instance, Hanover committed to cutting the city's energy consumption by 15%, switching heating off from April until September and turning off night-time lights illuminating city hall and museums. Paris switched off the lights off the Eiffel Tower an hour early, “thus sending a strong message to residents and visitors alike.”

Many governments have already launched public awareness campaigns to educate the population such as Austria's Mission 11, Ireland's Reduce Your Use, Finland's “A degree lower − saving energy towards winter”, Estonia's "Together we can handle the energy crisis” and others.

5. Scale up supply

An obvious solution is to get more gas from elsewhere, but it is also the hardest and only small gains are potentially on offer.

New gas supply developments typically have long lead times, so decisions to develop new resources today take several years to result in additional supply.

But the IEA says there is some potential upside. There is around 170 bcm of non-Russian gas that is currently being produced but wasted via leaks to the atmosphere or flared.

The World Bank and the Payne Institute’s Earth Observation Group suggest that nearly 13 bcm of gas was flared in the first three quarters of 2022 in African countries that could have been sold to the EU instead via spare existing export capacity in Algeria, Angola, Egypt and Nigeria. The IEA estimates that a further 7 bcm of methane was released into the atmosphere from oil and gas operations in these countries over this period. There are also near-term opportunities to scale up low-emissions gas supply, notably biogases.

Overall, the IEA estimates that additional actions in these areas could bring a further 4.5 bcm to market in 2023.

New policy efforts could also substantially reduce leakages. The Netherlands halved methane emissions from its offshore oil and gas industry in two years through an emissions reduction programme. Canada has introduced regulations that could save more than 0.5 bcm by 2025 (a near 40% reduction), and Angola reduced flaring volumes by more than 50% between 2016 to 2021 following its endorsement of the World Bank’s Zero Routine Flaring by 2030 initiative. Nigeria has also announced regulations to reduce methane emissions from its oil and gas sector, establishing leak detection and repair requirements, a ban on cold venting, and equipment standards.

The IEA estimates that around 4 bcm of additional natural gas could be made available to the EU in the next year with concerted efforts by African exporting countries, and incentives from buyers. Most of the identified potential that could be exploited in the near-term to bring additional gas to Europe lies in Algeria and Egypt.

Setting up biomethane production could add another 1 bcm in 2022, with France, Italy and Denmark accounting for the bulk of the growth.

France has launched tenders for new biomethane projects and Italy has introduced contracts to support biomethane production through its Recovery and Resilience Facility. Several countries are also establishing certification schemes to encourage gas offtakers to ensure a share of their gas requirements are biomethane.

New biomethane projects that start construction in the first quarter of 2023 could be operational before the start of winter and produce an estimated 0.6-1 bcm of additional gas.

Features

US expands oil sanctions on Russia

US President Donald Trump imposed his first sanctions on Russia’s two largest oil companies on October 22, the state-owned Rosneft and the privately-owned Lukoil in the latest flip flop by the US president.

Draghi urges ‘pragmatic federalism’ as EU faces defeat in Ukraine and economic crises

The European Union must embrace “pragmatic federalism” to respond to mounting global and internal challenges, said former Italian prime minister Mario Draghi of Europe’s failure to face an accelerating slide into irrelevance.

US denies negotiating with China over Taiwan, as Beijing presses for reunification

Marco Rubio, the US Secretary of State, told reporters that the administration of Donald Trump is not contemplating any agreement that would compromise Taiwan’s status.

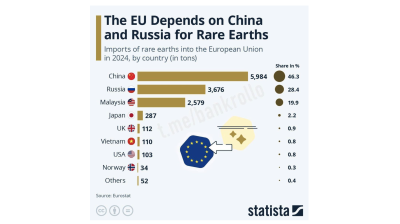

Asian economies weigh their options amid fears of over-reliance on Chinese rare-earths

Just how control over these critical minerals plays out will be a long fought battle lasting decades, and one that will increasingly define Asia’s industrial future.