Recent protests in Kenya have delivered a severe blow to President William Ruto’s fiscal consolidation plans. With the president dismissing his cabinet on July 11 in a bid to retain power, it appears increasingly likely that the government will struggle to service its public debt obligation and fears of a default have reappeared, David Omojomolo, an Africa Economist with Capital Economics said in a note.

“The chances of a sovereign default in the coming years are rising again, and would jump if the IMF were to pull its support,” says Omojomolo.

Kenya has run large budget deficits for much of the past 10-15 years. A surge in expensive infrastructure projects under former President Uhuru Kenyatta during the 2010s was a key trigger. With revenues proving insufficient, the government turned to borrowing, causing the public debt-to-GDP ratio to jump from 40% in 2010 to over 70% in 2023. Debt servicing costs now consume nearly 30% of government revenues. Public trust in the government has eroded, especially as projects have faced delays or failed to materialise amid corruption allegations.

President Ruto, who rose to power in 2022, outlined bold plans to stabilise public finances. Fiscal tightening formed a significant part of his strategy, with early measures including a housing levy, taxes on salaries and a fuel tax. These measures initially appeared successful, as the central government’s budget deficit narrowed from nearly 9% of GDP at the height of the pandemic to as low as 4.3% of GDP. Much of this progress was due to limited reductions in spending as a share of GDP, while revenues themselves barely increased.

Nonetheless, a narrower budget deficit and an improved balance of payments position helped Kenya avert a sovereign default earlier this year. Allowing the shilling to weaken supported a sharp narrowing of the current account deficit, reducing pressure on foreign exchange reserves. This, along with an IMF deal, enabled Kenya to undertake a partial buyback of its Eurobond that matured last month, greatly reducing fears of an imminent sovereign default. This was reflected in dollar bond spreads narrowing from nearly 1,000 basis points (bp) in early 2023 to less than 500 bp by March this year.

The 2024/25 budget outlined even more ambitious fiscal consolidation targets. Spending was set to fall through reduced tax administration costs and development spending. Planned tax increases on a range of goods and services, including vehicles, imported goods, and bread, were expected to generate KES 302bn (2% of GDP). The government estimated these measures would narrow the fiscal deficit from 5.6% of GDP in 2023/24 to 3.9% the following fiscal year, eventually reaching 3.3% of GDP by 2026/27. It also expected the debt-to-GDP ratio to decline from around 70% currently to below 60% by 2026/27.

Widespread protests, however, have halted these plans. Protesters, angry at what they perceived as the government exacerbating current cost of living challenges with the planned tax increases, stormed parliament, resulting in civilian deaths. In response, President Ruto scrapped the budget, fearing the protests could evolve into a larger threat to his power. He subsequently dismissed almost his entire cabinet, pledging to form a broad-based government across political lines.

“The scrapping of the budget leaves Kenya with a large fiscal shortfall to manage. President Ruto has few good options. With tax hikes now clearly off the table, he has been confronted with a choice between further spending cuts, as has successfully been implemented in the past, or simply increasing borrowing,” says Omojomolo.

In a speech last week, President Ruto presented a middle-ground solution. He announced that the budget deficit would narrow to 4.6% of GDP in the current fiscal year through a combination of lower spending and more borrowing. Some spending cuts are aimed at placating protesters, including postponing increases in government officials’ salaries, cutting public sector salaries, and tightening expenses for the president’s entourage.

“Still, even after these latest measures, the debt-to-GDP ratio looks set to rise this year. President Ruto has, so far, not been clear on how he expects the budget deficit will evolve further out. But it’s clear that more tightening will be needed to stabilise the debt ratio, let alone to get it to fall. We estimate the primary balance will need to improve by 1% of GDP to prevent the debt burden from rising,” says Omojomolo. “We think that will be difficult to achieve and expect the debt ratio will rise to around 73% by 2026.”

The IMF has so far remained vague about what this means for Kenya’s programme. The Fund's official statements have been non-committal, likely because the IMF, like Kenya, has few good options. There is significant criticism of the IMF’s alleged role in pushing the now-cancelled tax rises. Doing nothing risks signalling to other IMF recipients that there is no consequence for fiscal slippage. As a result, the IMF will likely delay releasing further tranches of Kenya’s financing package while the Ruto administration considers its medium-term strategy.

“The IMF pulling its financing programme is just one risk which could act as a trigger to tip Kenya even closer to sovereign default. Ruto stepping down is another, with protesters appearing to sense blood having caused the budget to be scrapped and now forcing the president to dismiss the vast bulk of his cabinet. Kenya’s debt repayment schedule remains another flashpoint on the horizon, with a $300mn Eurobond repayment due next year, and similar sizeable obligations due in the years after,” Omojomolo concluded.

Opinion

IMF: Global economic outlook shows modest change amid policy shifts and complex forces

Dialing down uncertainty, reducing vulnerabilities, and investing in innovation can help deliver durable economic gains.

COMMENT: China’s new export controls are narrower than first appears

A closer inspection suggests that the scope of China’s new controls on rare earths is narrower than many had initially feared. But they still give officials plenty of leverage over global supply chains, according to Capital Economics.

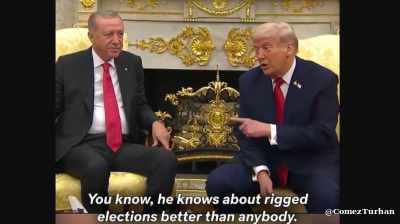

BEYOND THE BOSPORUS: Consumed by the Donald Trump Gaza Show? You’d do well to remember the Erdogan Episode

Nature of Turkey-US relations have become transparent under an American president who doesn’t deign to care what people think.

COMMENT: ANO’s election win to see looser Czech fiscal policy, firmer monetary stance

The victory of the populist, eurosceptic ANO party in Czechia’s parliamentary election on October 6 will likely usher in a looser fiscal stance that supports growth and reinforces the Czech National Bank’s recent hawkish shift.