Tunisia’s economy is deteriorating and it is now on the brink of an economic collapse. Its economy is shackled by unsustainable policies that have been in place since President Kais Saied’s political takeover in July 2021, and he has just been re-elected for another five years. The prospects for radical reforms and a change of direction are poor, say political analysts Ishac Diwan, Hachemi Alaya and Hamza Meddeb of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in a recent paper.

"Absent rapid reform," they assert, "Tunisia’s economic policies will plunge the country into an abyss."

At the heart of Tunisia’s growing crisis are two flawed policy choices that have characterised Saied’s economic approach. The first is an aggressive fiscal expansion that has led to historically high deficits for four straight years, pushing public debt to unsustainable levels.

Secondly, there is insufficient government support for productive economic activity, with a deteriorating business climate and heightened macroeconomic risks discouraging investment and halting growth. "All the elements are in place for a financial crisis that extends across public debt, foreign exchange and the banking sector."

“As a result of all this, there is a serious risk of a financial blowout. Tunisia is perilously close to having to dig into its financial reserves. There is no guarantee that the situation will remain contained until the elections. A financial crisis, if it erupts, risks inflicting on the country a harrowing mix of state bankruptcy, economic collapse, deep social wounds and major political challenges, given the need to distribute large losses across the population,” the analysts said.

Tunisia’s economic mismanagement is primarily self-inflicted. Rather than addressing the core structural problems that have plagued the country for years, Saied’s government has doubled down on policies that have only deepened Tunisia’s fiscal hole. His populist rejection of an International Monetary Fund (IMF) programme, coupled with a campaign against what he calls the "corrupt business elite," has led to economic stagnation. While these stances have garnered some popular support, the long-term consequences have been disastrous.

Saied’s refusal to work with the IMF is particularly damaging. Avoiding the IMF’s austerity measures may have spared the population immediate hardship, but it has also cut off a critical source of external financing. Without an IMF programme, Tunisia has increasingly had to rely on domestic borrowing to finance its deficits. This, in turn, has crowded out the private sector, lowered growth, increased inflation and put tremendous pressure on the banking system.

“The closing of external spigots is pushing the government to finance more of its large deficit domestically, through increased borrowing (from banks, national bondholders and the Central Bank).”

As a result, Tunisia’s financial situation has become increasingly precarious. Inflation is rising, real wages are falling and unemployment remains stubbornly high. Youth unemployment, in particular, is alarmingly high at 39%, and even among university graduates, 24% are out of work. The economic malaise is deepening social discontent, putting further strain on Tunisia’s already fragile social fabric.

The analysts also point out that government spending on subsidies has surged, further straining the country’s fiscal position. “The repercussions of flawed policies have already resulted in a decline in economic growth and a deterioration of social conditions,” they note. This increase in spending, designed to cushion the population from the worst effects of the economic downturn, has only made the fiscal deficit worse. At present, Tunisia’s public debt is nearly 100% of GDP, with fiscal deficits at a staggering 7.7% of GDP for four consecutive years.

In 2023, Tunisia recorded some of the lowest economic growth in over a decade, save for the pandemic year of 2020. Economic growth was just 0.4%, while inflation soared to a record 9.3%. Investment, both public and private, has collapsed, with national investment standing at a record low of just 12.8% of GDP, and private investment at only 7%. Meanwhile, exports, though relatively stable due to demand from Europe, Tunisia’s main trading partner, have been unable to counterbalance the domestic weaknesses caused by declining consumption, rising inflation and a fall in employment.

"The recession was caused by Tunisia’s domestic weaknesses," the analysts say. They point to declining agricultural output due to poor rains, the stagnation of the manufacturing sector and the overall deterioration of the business climate as the primary drivers of the economic slowdown. On the demand side, household consumption has plummeted as prices have risen, incomes have fallen and unemployment has worsened. Even high government spending has not been enough to compensate for the drop in demand.

Worryingly, inflation has been driven not by external factors like currency devaluation or high import prices, but by Tunisia’s own reliance on monetary financing. The Central Bank has been providing liquidity to keep the government afloat, either by refinancing banks or directly injecting funds since February 2024. "All indications suggest that inflation will remain high for the immediate future," the analysts caution, especially if the Tunisian dinar is forced to depreciate further to balance the country’s external accounts.

As 2023 came to a close, hopes for an improvement in fiscal accounts were dashed. The state deficit ended the year at 7.7% of GDP, mirroring the high levels seen in 2021 and 2022. Tunisia’s fiscal situation has been deteriorating for over a decade, with fiscal deficits ballooning in the aftermath of the 2011 uprising. From an average of 2.8% of GDP during the 2000s, deficits have risen dramatically, reaching 9.4% in 2020 due to pandemic-related spending, and have remained elevated since.

The analysts also draw attention to the rising debt burden, which has become a significant concern. Public debt now represents over 80% of GDP, and debt servicing has risen to consume 14.4% of GDP in 2024. The cost of servicing Tunisia’s debt has more than doubled in just four years, placing a huge strain on the country’s finances. At 10.4% of budgetary expenditure, debt servicing is now the third-largest item in the state budget, behind salaries and subsidies. "The rise of the debt burden is also worrisome," Diwan and his co-authors warn, as the government faces mounting challenges in rolling over its debt amidst a drying up of external financing options.

Tunisia’s external debt is another source of concern. Although external debt represents 56.7% of total public debt, and around 53.6% of GDP, the country’s lack of action to adjust its financing situation has made this debt riskier. The closure of international financial markets to Tunisia, combined with the rising cost of borrowing, has put further pressure on the government to rely on domestic borrowing. Yet this strategy is crowding out the private sector and increasing the risk of a banking crisis, as the banking system becomes even further exposed to public debt.

"The main budget line that has risen is social expenditure – subsidies and transfers – which have been extended as a safety net to offset the worsening economy," the analysts note. However, this safety net is only deepening Tunisia’s fiscal woes. Saied’s refusal to engage with the IMF means that the government is trapped in a cycle of overspending and borrowing, without the external support it desperately needs to stabilise the economy.

Looking ahead, the situation in 2024 is unlikely to improve without significant reforms. Tunisia faces a massive foreign funding gap, with only $1.5bn of the $5bn required to finance the 2024 budget sourced so far.

"The main challenge facing the state in the 2024 budget remains the large foreign funding gap, which would be very hard to secure under the current circumstances," the analysts say.

Furthermore, Tunisia’s reliance on domestic borrowing is crowding out private sector financing, stifling economic growth and perpetuating a vicious cycle of low investment, high inflation and burgeoning debt. "The Tunisian economy is now very much below its potential. Its problems are self-inflicted," the analysts conclude. With external funding sources drying up and domestic financing options becoming more limited, Tunisia’s economic future looks increasingly bleak.

Tunisia’s only path out of this quagmire, according to the analysts, is a bold reform programme that tackles its structural weaknesses, reduces fiscal deficits and attracts investment. But time is running out. The year 2024 will be crucial in determining whether Tunisia can avert a full-blown financial crisis, or whether it will plunge deeper into economic and social turmoil.

Opinion

COMMENT: Hungary’s investment slump shows signs of bottoming, but EU tensions still cast a long shadow

Hungary’s economy has fallen behind its Central European peers in recent years, and the root of this underperformance lies in a sharp and protracted collapse in investment. But a possible change of government next year could change things.

IMF: Global economic outlook shows modest change amid policy shifts and complex forces

Dialing down uncertainty, reducing vulnerabilities, and investing in innovation can help deliver durable economic gains.

COMMENT: China’s new export controls are narrower than first appears

A closer inspection suggests that the scope of China’s new controls on rare earths is narrower than many had initially feared. But they still give officials plenty of leverage over global supply chains, according to Capital Economics.

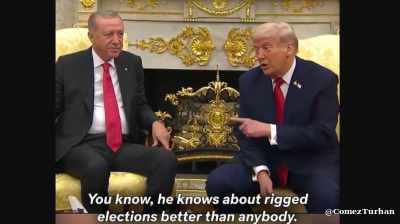

BEYOND THE BOSPORUS: Consumed by the Donald Trump Gaza Show? You’d do well to remember the Erdogan Episode

Nature of Turkey-US relations has become transparent under an American president who doesn’t deign to care what people think.