COMMENT: With Trump back in the White House, Europe may need to turn to Turkey to strengthen its security

On the eve of Donald Trump’s inauguration, it is clear the EU and Turkey must finally get serious about security cooperation.

The argument was lately advanced in an assessment by Chatham House senior consulting fellow Galip Dalay. Noting that Trump’s commitment to Nato is questionable (and that’s putting it politely), he suggests that the EU cannot hope to deter Russia effectively without closer cooperation with Ankara.

“With Donald Trump’s forthcoming [January 20] inauguration, the question of the future of the European security order has become more pressing – and so has the need for clarity about Turkey’s place and role within that order. In this respect, Trump’s return might provide much needed impetus for the European Union and Turkey to finally engage in more serious dialogues on European security and on broader foreign and security policy cooperation,” says Dalay, who consults for the Turkey Initiative, Middle East and North Africa Programme at the British think tank, otherwise known as the Royal Institute of International Affairs.

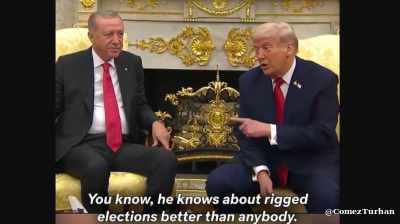

Back in November, two days after Trump won re-election, Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan showed a newfound confidence in his dealings with Europe—even a certain cockiness—as he addressed the fifth European Political Community summit in Budapest. Turkey’s hopes of EU membership have essentially made little progress for decades, but could it be that Erdogan, sensing European foreboding in the face of Russia’s unrelenting aggression and attrition in Ukraine, sees that playing the Turkish defence card could finally open doors.

“Türkiye’s full inclusion in the European Union’s defence efforts is indispensable for Europe’s peace and security,” Erdogan told fellow national leaders gathered in the Hungarian capital, amid speculation over whether Trump could even go so far as to withdraw the US from Nato.

Should the unthinkable happen, that would actually leave Turkey as the Nato member with the largest land forces in the defence bloc.

Projection of power

The standing of Erdogan—long intent, at the expense of Russia and Iran where necessary, to build up Turkey’s ”full moon” projection of power, commerce and influence across the Middle East, Africa, the South Caucasus and Central Asia—has, of course, since the summit in Hungary been further boosted by the fall of the Bashar al-Assad regime in Turkey’s southern neighbour Syria.

The prevailing wisdom is that without Ankara’s backing, the militias who sent Assad fleeing to Moscow could not have triumphed. Turkey denies having taken a direct role, but Trump for one is having none of it. In an apparent loose reference to Turkey’s Ottoman past, the American president-elect, who had a somewhat erratic relationship with Erdogan during his 2017 to 2021 first stint in the Oval Office, said in mid-December: "They've wanted it for thousands of years, and he [Erdogan] got it, and those people that went in [to Damascus] are controlled by Turkey, and that's OK."

Reflects Dalay: “Europe’s security environment has undergone a radical transformation in recent years. After the Ukraine war, the once prevalent idea of a security order that included Russia has been replaced by one that places Moscow firmly in the adversary camp. Similarly, the Gaza war, and the downfall of Syria’s Assad regime have fundamentally changed the geopolitics of the European neighbourhood, both in the East and South.

“Such changes necessitate a fresh approach that treats European security in the broader sense, bridging the gap between EU and non-EU European NATO member states. A structured foreign and security dialogue between [non-EU states] Turkey, the UK and Norway and the EU is essential. Going forward, this dialogue should also aim to include non-EU and non-NATO European states such as Ukraine.

“For European security, Russia remains the most immediate threat, and Europe cannot afford to have a security order that is set against Moscow and excludes Turkey simultaneously. The Black Sea, Eastern Mediterranean, and Middle East are not separate zones in Russian-Western confrontation. Rather, they are largely a single space. And Turkey straddles all these regions.”

The war in Ukraine will soon enter its fourth year. There is serious consternation and anxiety in Europe over how the conflict might evolve if US support for Kyiv under Trump falls off. With such tension in the air, it is little wonder that criticism in European capitals of Turkey’s defiant failure to respond to European human rights concerns has faded into the background. Arms embargoes introduced against Ankara partly in response to those concerns are gradually being removed, and in trade Turkey is showing renewed optimism in lobbying for a better customs union deal with the EU, by far its biggest export market.

In October, Berlin approved a substantial package of arms exports to Ankara, including materials for the modernisation of Turkish submarines and frigates. In November, Germany also finally withdrew its veto against the sale of Eurofighter Typhoon jets to Turkey.

More invites from Brussels

Also, with the easing of the Eastern Mediterranean crisis—in which Turkey has in recent years been pitted against Greece, Cyprus and Paris in disputes over territory and associated offshore gas resources—Ankara has been getting more invites from Brussels. In August the EU invited Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan to the Gymnich meeting, an informal gathering of the EU ‘s top diplomats held every six months. This illustrates, says Dalay, “an atmospheric change in relations”.

Concludes the analyst: “Being in the room does not guarantee alignment – both sides have different geopolitical priorities and interests. But attendance at the Gymnich meetings should be the first step towards a more structured foreign and security policy dialogue – providing reassurance for both parties as the Trump administration begins, bringing with it considerable uncertainties.”

Opinion

COMMENT: Hungary’s investment slump shows signs of bottoming, but EU tensions still cast a long shadow

Hungary’s economy has fallen behind its Central European peers in recent years, and the root of this underperformance lies in a sharp and protracted collapse in investment. But a possible change of government next year could change things.

IMF: Global economic outlook shows modest change amid policy shifts and complex forces

Dialing down uncertainty, reducing vulnerabilities, and investing in innovation can help deliver durable economic gains.

COMMENT: China’s new export controls are narrower than first appears

A closer inspection suggests that the scope of China’s new controls on rare earths is narrower than many had initially feared. But they still give officials plenty of leverage over global supply chains, according to Capital Economics.

BEYOND THE BOSPORUS: Consumed by the Donald Trump Gaza Show? You’d do well to remember the Erdogan Episode

Nature of Turkey-US relations has become transparent under an American president who doesn’t deign to care what people think.