Once sedate and dull, Czech politics has recently been serving up non-stop political drama. First, October’s parliamentary elections dealt a shattering, but not fatal, blow to established parties.

Then the election winner, the billionaire-politician and fraud indictee, Andrej Babiš struggled to form a government with any of the other eight parties in parliament, opting instead in December to form a minority administration with uncertain prospects (it faces a vote of confidence on January 10).

Now creeping up on us after a low-key campaign come the Czech presidential elections, whose first round takes place on 12-13 January.

The relatively low profile of the election is partly down to the incumbent. Having announced in March that he would run for a second term, President Miloš Zeman has opted for a Czech version of a [US] “Rose Garden Strategy” by officially not campaigning, refusing to give pre-election interviews or appear in debates with other candidates; and according to his online campaign account spending pretty much zilch.

The reality is that for many months presidential visits to regions and provincial towns, fielding undemanding questions from generally sympathetic crowds, have served as a surrogate, under-the-radar campaign.

Zeman’s non-campaign

Zeman’s non-campaign now also features expensive-looking billboard and newspaper advertising to elect Zeman Again (Zeman znovu) paid for by the Friends of Miloš Zeman – a previously dormant civic association founded in 2008 to relaunch Zeman from political retirement.

To some extent, these tactics seems to reflect Zeman’s state of health. Although rumours of cancer and other life-threatening conditions has been vigorously rebutted, the president suffers diabetes and a nerve condition – possibly arising as a complication – affecting his legs which visibly limits his mobility. The president’s alcohol and tobacco consumption have also long been a source of concern to his doctors.

In other ways, however, Zeman’s semi-visible campaign is a shrewd political move. For supporters Zeman is a flawed, but decent politician, who stands up for the interests of ordinary people outside the better-off world of Prague and big cities and also sticks up for Czech national interests. For his many detractors Zeman is a boorish authoritarian illiberal nationalist and a national embarrassment, tarnishing the Czech Republic’s good name.

As well as lapses of decorum such as appearing drunk at ceremonial occasion and using the c-word in a radio broadcast, Zeman has shared a platform with fringe anti-Islamic extremists and come out as the only EU head of state to publicly endorse Donald Trump before the US elections in 2016.

More worrying still has been his cavalier attitude to the Czech constitution. His appointment in 2013 of a presidential caretaker government of supposed technocrats over the heads of political parties flouted previous constitutional practice. He has at various times, suggested that, creatively interpreted, the constitution could him allow him to dismiss the government; leave ministers in office following a prime minister’s resignation; or leave his ally prime minister Andrej Babiš in office, rather than dissolve parliament if all three constitutionally allowed attempts at forming a government were exhausted.

Polls suggest, however, that Zeman, who has been picking up support since the launch of the December billboard, has a solid base of support predominantly among poorer, older, more left-wing, less well-educated Czechs. He is likely to top the first-round poll by a clear margin with 43-44% of the vote, but may face a stiffer contest in the second, run-off round on 26-27 January.

The challengers

As in the first direct presidential elections in 2013, Zeman faces eight challengers. However, this year political parties have taken a back seat. Many have realised that they simply lack a broad enough appeal or any credible enough candidates to have a serious run at the presidency.

The one party that could have done so, Babiš’s ANO movement – said at one time to have considered running the popular defence minister (now foreign minister) Martin Stropnický for presidency – chose not to do so: for Babiš keeping to his informal pact with Zeman and getting into government were by the important priorities. If, as expected, his new minority administration loses its upcoming parliamentary vote of confidence, Zeman will play a key role by re-nominating Babiš as prime minister for a second, and probably decisive, effort a forming a government.

All of but two of Zeman’s challengers are thus non-party independents running on vague centrist or centre-right platforms. Former prime minister Mirek Topolánek, who headed a Civic Democrat-led (ODS) governments of 2006-9, running as independent, also seems to be attracting some backing from parts of his former party, helped by outspoken attacks on Zeman questioning the president’s health.

Polls suggest, however, that Zeman has only two serious challengers: Jiri Drahoš, the former head of the Czech Academy of Sciences, and the journalist, lyricist and music producer turned betting tycoon and philanthropist, Michal Horáček. Although Horáček has waged a slicker campaign, most polls show him in third place with Drahoš the clear favourite to make it into the run-off against Zeman on 26-27 January.

President Drahoš?

Although keeping a (for him) low profile, Zeman has had a good campaign. He has been picking up support following the launch of December’s billboard campaign, with bookmakers’ odds making him the clear favourite and little sign of his rivals generating much momentum or public excitement.

However, polls still suggest that Zeman will lose by a clear margin in a run-off against Drahoš, who is forecast to gain most of the first round votes cast for other candidates – emulating a strategy seen in presidential elections in Slovakia and Romania in 2014, when previously little-known independents overhauled seemingly dominant left-wing populists in the second round.

Throughout Drahoš has cultivated a centrist and non-confrontational image, telling interviewers that he had a vision, but no political programme. He also made clear that he would be more than willing to work with Babiš, who he saw as a mainstream politician with a clear electoral mandate whose government deserved the backing of other mainstream parties.

Zeman will, therefore, be hoping that his non-campaign has been well pitched enough to rally his core support among poorer, older, less well-educated Czechs, while leaving diverse groups of voters opposed to him unmobilised. His most likely path to victory would be to get enough votes behind him to narrowly win the election outright in the first round. The fact that his key challengers are dignified public personas and good CVs, rather than any compelling positive vision of a liberal and outward looking Czechia may turn out to be Zeman’s greatest asset.

Seán Hanley is Senior Lecturer in Comparative Central and East European Politics at University College London. This post first appeared on his personal academic blog.

Opinion

IMF: Global economic outlook shows modest change amid policy shifts and complex forces

Dialing down uncertainty, reducing vulnerabilities, and investing in innovation can help deliver durable economic gains.

COMMENT: China’s new export controls are narrower than first appears

A closer inspection suggests that the scope of China’s new controls on rare earths is narrower than many had initially feared. But they still give officials plenty of leverage over global supply chains, according to Capital Economics.

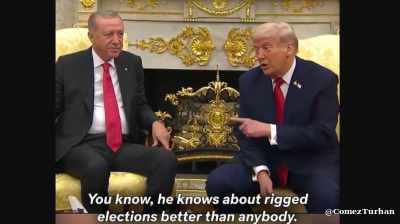

BEYOND THE BOSPORUS: Consumed by the Donald Trump Gaza Show? You’d do well to remember the Erdogan Episode

Nature of Turkey-US relations has become transparent under an American president who doesn’t deign to care what people think.

COMMENT: ANO’s election win to see looser Czech fiscal policy, firmer monetary stance

The victory of the populist, eurosceptic ANO party in Czechia’s parliamentary election on October 6 will likely usher in a looser fiscal stance that supports growth and reinforces the Czech National Bank’s recent hawkish shift.