Goldman Sachs metals strategist Nick Snowdon has warned that forecasts of copper prices hitting $15,000 per tonne may be conservative.

As supply-side shocks caused by global warming and lockdowns rumble on, demand is due to skyrocket in step with growing renewable energy and electricity infrastructure.

The result could see the copper price soar to new highs, Snowdon told Bloomberg’s Odd Lots podcast.

The prices of base metals already spiked dramatically in response to the conflict in Ukraine, with copper jumping 10% to an all-time high. The copper price rose further to over $1,000 per tonne in June as China showed signs of easing coronavirus (COVID-19) restrictions, fuelling optimism about global manufacturing.

Falling output in Chile and conflict with communities near copper mines in Peru have exacerbated supply problems in the world’s two largest copper-producing countries. In Chile, manufacturers have had to resort to using seawater and desalination plants due to droughts in the Antofagasta and Atacama regions. Little solace can be found in exchange warehouses, where supplies of the red metal are very low.

Meanwhile, demand for copper is forecast to increase, driven by the green transition and increased uptake of technology. Due to its high conductivity, copper is used in solar panels, electric cars, wind farms and electricity grids.

Rystad Energy forecasts that greater adoption of electric vehicles (EVs) in countries like China and India will see copper demand jump 16% by 2030, when it is forecast to reach 25.5mn tonnes.

Snowdon agreed with the gloomy projections. “By the end of the decade, [we’re forecasting] the largest ever long-term deficit. It’s just an impossibly tight future,” he said.

A similar dynamic can be observed in the prices of other commodities, which periodically jump above their cost curves. Currently, lithium is trading at almost six times its cost curve due to imbalances in supply and demand. Lithium’s limited production globally coupled with its use in EV batteries make it particularly susceptible to price swings. Sales of EVs doubled last year to 6.6mn, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

Optimists point to increasing copper output in some parts of the world, however. The hope is that the start of production in new developments like Serbia’s Timok, Russia’s Udokan and Peru’s Quellaveco will begin to normalise price growth.

The Timok Copper and Gold project is one of the world’s top ten undeveloped high-grade, super-large copper-gold mines. It has around 1.2mn tonnes of 2.7% graded copper. When the project reaches its full capacity, Timok is anticipated to produce over 79,000 tonnes per year (tpy) of copper.

Peru’s Quellaveco mine, run by Anglo American, will be one of the country’s largest copper mines. It expects to deliver an average of 300,000 tpy of copper in the first ten years of operation. The first copper production is expected later in 2022. With ore grades at existing deposits declining, output from existing mines is set to fall from 2025. The imminent opening of more copper mines like Quellaveco and Timok should go some way towards smoothing copper’s global supply-side snags.

Russia’s Udokan Copper plans to start production a little after Quellaveco and Timok, in the first half of 2023. With more than 26mn tonnes of copper resources, Udokan is the world’s third-largest untapped deposit, following America’s Pebble and Resolution Copper.

Udokan is located in Russia’s Far East, near the Baikal-Amur mainline – a railway artery running across Russia. So it is well positioned to ease some of the demand coming from Asia, especially from China and India. Valery Kazikaev, the chairman of the board at Udokan, wrote in a special edition of the Economic Times on Sunday that “Russia, one of the world’s major exporters of refined copper, is ready to cover India’s growing requirement for the metal supported by higher demand from EVs and renewable energy.”

Projects like Udokan, Quellaveco and Timok can go some way towards alleviating the dearth in copper production. But Snowdon points out that this minor relief may not be enough to bring down prices. “The bull market of the 2000s was nearly entirely solved by supply responses, and then that very rapid increase in mine investment. That’s clearly not going to be the majority solver this time, though,” he warned.

Data

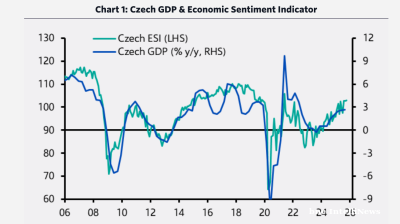

Czech growth accelerates as domestic demand-side pressure builds

The Czech economy delivered an unexpected acceleration in the third quarter, marking a clear shift from its earlier position as a regional underperformer to one of Central and Eastern Europe’s fastest-growing economies.

Eurobonds of Istanbul-listed Zorlu units offer attractive yields amid rating downgrades and no default expectation

Debut paper currently offering 14-15% yield.

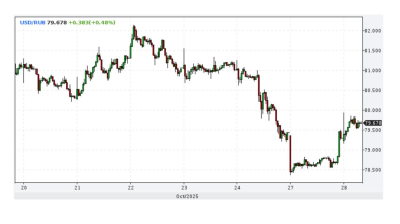

Ruble strengthens as sanctioned oil companies repatriate cash

The Russian ruble strengthened after the Trump administration imposed oil sanctions on Russia’s leading oil companies, extending a rally that began after the Biden administration imposed oil sanctions on Russia in January.

Russia's central bank cuts rates by 50bp to 16.5%

The Central Bank of Russia (CBR) cut rates by 50bp on October 24 to 16.5% in an effort to boost flagging growth despite fears of a revival of inflationary pressure due to an upcoming two percentage point hike in the planned VAT rates.