The economic crisis resulting from the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic will be deeper and longer in the CIS, Ukraine, Turkey and the Western Balkans than in the EU member states of Central and Southeast Europe that are much better equipped to deal with it was the key takeaway from the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies’ (wiiw’s) webinar on March 18.

The Vienna-based think tank has already slashed its forecast for this year to just 1.1% across the Central, Eastern and Southeast Europe (CESEE) region, but warns that the situation could worsen considerably.

The consensus is now that countries in the region are likely to follow Italy — that as of March 19 had over 30,000 cases — despite their efforts to contain the virus. While cases in countries in the region are so far numbered in hundreds rather than thousands, governments have introduced lockdowns with a crippling effect on their economies, to delay the peak of the epidemic and reduce the pressure on their healthcare systems.

wiiw deputy director Richard Grieveson forecasts restrictions could be relaxed after around six weeks, but may be reintroduced in case of further waves of infection. And while there may be a tentative recovery this year, a return to normal economic life is not expected until a vaccine is found — “our best estimate is around 18 months,” he says, which would mean no real recovery before 2021.

wiiw economists consider the best case of a recession in H1 followed by recovery in H2 is now looking highly optimistic and increasingly unlikely. Taking China has a guide would mean a contraction of 3-4% this year for all countries. However, said Grieveson, for some countries in the region the contraction will be much worse.

The only good news is that previous experience has shown that a crisis caused by health factors — rather than a financial crisis — tends to be followed by a strong recovery.

“We are all Italy”

The crisis was initially seen as an external problem, with countries facing contagion from the outbreaks in first China and later Italy — both major trading partners of countries in the region. It was therefore expected mainly to hit the Central European economies whose automotive industries are closely linked to China as a supplier, as well as the Western Balkans which have close trading relationships with Italy.

But the spread of the virus in recent weeks has shown that “We are all Italy,” said Grieveson.

“Now it is clear that all countries have the virus and have to deal with containment or slowdown of the virus spread,” said wiiw economist Olga Pindyuk. On top of this, the major oil exporters — Russia and Kazakhstan — have already been hit heavily by the oil price crash.

With the virus is now spreading within the region, the poorer countries to the east and southeast are expected to fare much worse than the richer EU members of Central Europe.

“Even before the really big developments of the last week we expected material negative impact on economies in every country. We think the impact will be much worse in the CIS, Ukraine, Turkey and the Western Balkans,” Grieveson said.

When it comes to how seriously an economy will be affected by the crisis, Grieveson identified two key indicators: the quality of the health system and the fiscal space to act.

Some health systems are in a “very bad position”, he said, while a lot of countries in the region “will not be able to react in a big way fiscally”.

While the scale of the pandemic is unprecedented in recent decades and its impact on healthcare systems thus hard to predict, metrics such as healthcare spending and the number of beds per 100,000 of the population show a clear divide between Central Europe on the one hand and the Western Balkans and CIS plus Ukraine on the other. The same metrics show that Italy is in a better position than virtually all of the CESEE countries — indicating that countries from the region will find their healthcare systems overwhelmed more quickly than Italy’s as the number of infections rises.

The other issue is which countries have the financial firepower to respond to the crisis. “We already see a situation where some countries are in a much better position, have better policy options to support the economy than others,” said Grieveson.

“What really matters is what happens on the fiscal side. Fiscal stimulation is going to be the key to how bad this gets. There are two groups in the region — EU and non EU.

“There is a difference between countries that can borrow and spend Western European style, and those that will hit the limits quickly and have to go to the IMF. While developed countries have the resources to deal with such a crisis, emerging markets are set to be locked out of international capital markets.”

In the last few days alone, Poland said it would spend a total of PLN212bn (€47bn) to help the economy that is being crippled by the outbreak of the coronavirus; the Lithuanian government adopted a stimulus package worth €5bn; and Croatian Prime Minister Andrej Plenkovic presented a package of measures to help the economy worth more than HRK30bn (€4bn).

On the other hand, Pindyuk singles out the example of Ukraine, which, she says, has “very limited options for dealing with the situation”. Not only have the social distancing measures taken so far by the authorities have not been very successful — she points, for example, to the decision to close the metros in major cities which instead pushed commuters onto overcrowded buses — but the recent reshuffle by President Volodymyr Zelenskiy that swept out the inexperienced young reformers alarmed investors, and the decision to sack the National Bank of Ukraine (NBU) management has lowered Ukraine’s chances of a new IMF deal at a time when the fund's support is likely to be needed more than ever.

On the monetary side, there has already been action by central banks in the region both to provide stimulus measures and to defend the economy. Some have adopted monetary easing policies, including the first ever quantitative easing in Poland, and big interest rate cuts in Turkey, the Czech Republic and Serbia, while Hungary is extending liquidity support for banks.

At the same time, some central banks have had to sell foreign currency to prop up their own currencies — Russia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan and Serbia have all done this and more central banks are expected to follow.

Features

Washington has a new focus on a Caspian energy play

For most of the last three decades since winning independence, Central Asia has been a bit of a backwater. Not any more. The Trump administration is becoming more focused on Turkmenistan's vast gas reserves and can smell money and power there.

BOTAŞ and Turkey’s hub ambition: from “30-year dream” to cross-border reality

For Ankara, the symbolism is as important as the molecules: Turkey’s energy map is shifting from end-market to hub.

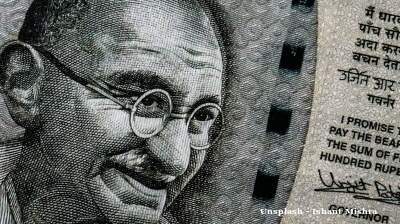

Indian bank deposits to grow steadily in FY26 amid liquidity boost

Deposit growth at Indian banks is projected to remain adequate in FY2025-26, supported by an improved liquidity environment and regulatory measures that are expected to sustain credit expansion of 11–12%