The number of Turkey analysts who still believe challenger Kemal Kilicdaroglu can dethrone Recep Tayyip Erdogan has become vanishingly small. The official results that confounded the pundits and opinion polls gave the strongman a surprisingly clear margin of victory in the first-round presidential vote two weeks ago. The result of the second-round runoff—taking place this weekend on Sunday May 28—is widely expected to be a formality.

Many on the markets yearned for a President Kilicdaroglu. They dreamt he would return Turkey to the path of economic orthodoxy, administering the painful but necessary medicine to deliver the Turkish economy from the hyperinflationary nightmare that has engulfed it under the populist economic management of the headstrong Erdogan—the president of two decades who reckons himself an economist. Turkey is not incapable of major surprises, but a President Kilicdaroglu now seems too much to hope for.

So what economic bombs might detonate under a President Erdogan entering his third decade of rule?

The Turkish lira is the obvious candidate for more mayhem should investors take fright at the sight of Erdogan still at the helm. Some analysts think another Turkish currency crisis is not far off.

In 15 years, the sorry currency has lost around 95% of its value against the dollar. As the markets drew to a close on Friday May 26, for the first time ever the Turkish lira (TRY) was moored at 20 to the USD. On the Istanbul Grand Bazaar unofficial free market, the rate has been pulling away into the 20s, creating an alarming spread against the interbank market for officials.

How far could the lira fall? Capital Economics said in a note this week on financial market prospects under a re-elected Erdogan that in short “we think that measures of Turkey’s risk premia would increase significantly and the pace of the lira’s depreciation against the dollar would pick up, driving the currency to 26/$ by end-2023”.

Kilicdaroglu has pledged that as president he would restore the independence of Turkey’s central bank. Erdogan the all-powerful will do no such thing. The best the markets can hope for is that, once safely re-ensconced in his 1,000-room Ankara palace, he will shamelessly see what’s good for him and perform several u-turns. At that point, rate hikes could be on the cards, despite Erdogan’s reiteration on the campaign trail of his baffling “thesis” that “interest rates and inflation are directly proportional—the more you lower interest rates, the lower the inflation rate… interest is the cause, inflation is the effect.”

So out of control is inflation in Turkey that on May 22, local business daily Ekonomi reported that it was cheaper for Turks to go to Egypt or Greece for a vacation rather than to a domestic destination. And, as this publication has regularly pointed out in recent years, there are many millions of Turkish households with hunger issues.

Kilicdaroglu, with the odds stacked against him, on May 24, appeared in a highly anticipated online show, Babala TV’s Mevzular Acik Mikrofon (Issues, Open Mic).

The Turkish Statistical Institute (TUIK, or TurkStat) says Turkey’s consumer price index (CPI) inflation stood at 44% y/y in April versus 51% y/y in March. But few in Turkey believe the official data (Kilicdaroglu has said that under him orders would go out to probe the country’s dodgy data).

The Istanbul-based ENAG inflation research group of economists put April inflation at a sky-high 105% y/y compared to 113% y/y in March.

Turkey’s central bank is known for burning through tens of billions of FX reserves in no time at all when it faces acute resistance to its attempts at putting a brake on the fall of the lira. It spent towards $20bn in the six weeks prior to the elections attempting to prop up the currency.

It has little firepower left.

In the six weeks leading up to the elections, the central bank’s FX reserves plunged by $17bn. The net FX reserves fell into negative territory for the first time since 2002. Excluding swaps, they stood at minus $60bn as of May 19. The gross reserves declined by $25bn in the two months to that date to $102bn.

“There’s a growing demand for dollars and gold in the market,” Enver Erkan, chief economist at Istanbul-based brokerage Dinamik Yatirim Menkul Degerler, was reported as saying by the Financial Times on May 18, adding: “The central bank is doing whatever it can, but that’s not a sustainable approach, because there’s not much left in the tank, in terms of reserves.”

Looking at the lira, Piotr Matys, senior FX analyst at In Touch Capital Markets, last week advised: "Should Erdogan be re-elected, the lira may be allowed to trade far more freely after being supported by backdoor FX interventions [prior to the elections], which are not sustainable over the mid-term horizon.

"Unless the CBRT [Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey] raises interest rates significantly, the lira may drop precipitously if backdoor FX interventions stop or are reduced markedly."

Market observers in the past week also kept a close eye on Turkey’s credit default swaps (CDS). The CDS measure the cost of insuring a country’s debt against default. At around 480 bp before the election, they have in the past two weeks passed the 700 bp mark before recovering a little ground.

Turkey now pays a higher premium than similarly-rated countries such as Honduras, Iraq and Mongolia, which have traded at or near distressed levels in recent months, according to a Bloomberg index tracking emerging market debt.

The yield on the Turkish government’s 10-year eurobonds lately moved past the 10%-level.

Another flashing red light resulting from what critics say is Erdogan’s prolonged economic mismanagement—designed to deliver growth-at-all-costs despite the ever more damaging cycles of boom-and-bust that that entails—is the country’s gaping external current account deficit. The gap, having ballooned to around 6% of GDP, was running at $54bn on a 12-month trailing basis in March, close to the all-time highs over the past decade.

The main index BIST-100 on the Borsa Istanbul lost around 4% to 4,581 in the month to May 26, but most foreign investors anyway long ago pulled out of trading on the controversial exchange.

Kilicdaroglu describes the Istanbul bourse as “a tool of robbery”. He outlined the accusation in an early May interview with Bloomberg, in which he also called for an investigation into the exchange.

A final illustration of Turkey’s economic ill-health is the fact that its FX-protected deposits scheme (KKM), introduced by the regime as an incentive to Turks not to flee their currency, reached $121.5bn as of May 19. It is posing a major contingent liability to government finances as the lira depreciates against the dollar.

In comments to Bloomberg on the prospect of Erdogan continuing in power, Cem Karacadag, head of emerging markets sovereign debt at Barings, said last week: “It’s bad news for investors, as it implies a heightened probability of the continuation of bad structural and macro policies.”

“All the nominal variables are wrong – interest rates, exchange rate, and prices – so savings and investment decisions become short-sighted, if not impossible,” Karacadag also said, adding that the current situation was “not a tenable investment thesis for investors”.

Even if Kilicdaroglu were to pull off a stunning victory on Sunday, bringing about a return by Turkey to economic orthodoxy would involve overcoming monumental macro challenges, as Francesc Balcells, chief investment officer of emerging market debt at FIM Partners, wrote in a May 15 opinion piece for the FT.

Balcells observed: “There will be a temptation to think that with Erdogan more likely [following the May 14 first-round vote] to retain control, markets will settle back to the status quo ante before the election.

“That’s unlikely. For investors, what has kept Turkish risk in check over the past few years has partly been the combination of financial repression — or the government’s capture of domestic dollar savings and control over financial flows to keep the lira stable — and the selling of assets such as reserves.

“And the expectation of a change in economic policy direction at some point down the road.

“Whilst financial repression will continue under Erdogan, the room to manoeuvre is getting narrower by the day, with each measure imposed by the government having a knock-on effect on different economic actors.”

Balcells noted that, admittedly, economists and market participants have been pointing out the unsustainability of the Turkish economic model for years, “but the damage to the balance sheet has never been as deep as it is today. In other words, initial conditions have never been as weak relative to previous crises.”

Offering some hope, Balcells said it was not impossible that “Erdogan could have an ideological epiphany on the economy. Or maybe, with a more comfortable majority in power, he could come to the more prosaic realisation that the only way out from the current economic predicaments is orthodoxy.”

But, he concluded, as things stand “the country will continue to walk on the edge of the precipice, if only one or two steps closer now. Markets will have to reprice accordingly, taking a dimmer view on Turkish credit, and incorporating a higher probability of a financial accident”.

Features

What Central Asia wants out of the upcoming Washington summit

Clarity on critical minerals and a lot else.

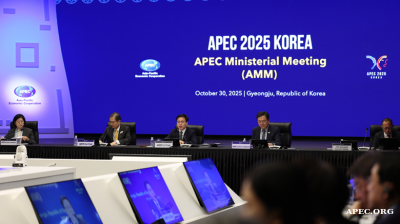

Global leaders gather in Gyeongju to shape APEC cooperation

Global leaders are arriving in Gyeongju, the cultural hub of North Gyeongsang Province, as South Korea hosts the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation summit. Delegates from 21 member economies are expected to discuss trade, technology and security.

Project Matador marks new South Korea-US nuclear collaboration

Fermi America, a private energy developer in the United States, is moving ahead with what could become one of the most significant privately financed clean energy projects globally.

_Cropped_1761809941.jpg)