Estonia, once a poster child among Eastern European members of the EU, has just finally emerged from more than two years of recession, with GDP falling 1% y/y in the second quarter but rising a feeble 0.2% q/q.

The once dominant ruling Reform Party has lost a lot of support and Kaja Kallas, whose term as premier started in 2021, just before the recession bit, is – barring a last minute upset – parachuting out of the country into the job of the EU’s next high representative for foreign affairs. What went wrong and can her successor Kristen Michal get the economy moving again?

Many EU countries have struggled to restart growth since the COVID-19 pandemic and the energy price spike caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. But Estonia was the only European country that was stuck in recession for so long, Andrei Korobeinik, an opposition member of the Estonian Parliament, the Riigikogu, told bne IntelliNews. “This is not only embarrassing but also has practical implications,” he emphasises.

Peeter Raudsepp, Director at the Estonian Institute of Economic Research, spells those implications out. “Estonia's international competitiveness is declining, the state's finances are no longer in order, the rising level of taxes will make the situation in our economy worse in every way for a long time to come,” he warns.

“The Estonian government has no plan for economic development….The war in Ukraine or other problems cannot be an excuse, because our neighbours have fared much better than us,” says Raudsepp.

He adds: “Estonia has lost or played down its advantages. Today we need more innovation to produce and export higher value products. The products we have exported till date are of too low value to be produced with much higher production costs.”

In a written reply to bne IntelliNews, Estonian President Alar Karis, an independent who was backed by the governing parties, points to three main reasons for the stubborn downturn.

Firstly, according to him, Estonia has been hit harder than its neighbours by economic weakness in Scandinavia as it has deeper links there, especially in Sweden, than the other two Baltic states, Lithuania and Latvia. “Weaker demand and depreciating exchange rates in Scandinavia have made exporting harder and companies need to look for new markets to export. It is not an easy task,” Karis says.

Secondly, according to the president, Estonian private sector indebtedness is higher – and has always been higher – than in Latvia and Lithuania, meaning that domestic demand has been hit harder by rising interest rates. “This could explain why some domestic-demand-oriented industries, for example, construction, have been doing much weaker in Estonia than in other Baltic states,” the president explains.

Thirdly, he says, Estonia saw a mini-boom at the end of 2021, which affected wage expectations and domestic demand, and the country is now coming down from that.

Estonia’s key economic figures clearly show the distress the country finds itself in.

GDP has declined y/y since 2Q2022, a total of nine consecutive quarters, but rose by 0.2% q/q in Q2, therefore technically emerging from recession, though it does not feel like that.

In July, Estonia’s annual inflation at 3.5% per cent was surpassed in the EU only by that in Belgium, while in neighbouring Latvia it was 0.8% and 1.1% in Lithuania.

Estonia's exports of goods fell by 14% in June, year-on-year, while imports fell by 11% over the same period, state agency Statistics Estonia reported. The trade deficit stood at €268 million, a rise of €20 million, year-on-year.

Estonia's traditionally frugal general government budget deficit amounted to €629 million, 1.6% of the estimated gross domestic product (GDP) for the full-year at the end of June. The deficit was €238 million higher than a year earlier. In the first half of this year, Estonia saw the fastest growth in public debt among the EU27, reaching 23.6%, according to Eurostat.

Is the Estonian free market model of low taxes, balanced budgets and thrusting internet startups therefore no longer viable?

Rasmus Kattai, Head of Economic Policy and Forecasting at the Pank of Estonia, the country’s central bank, says Estonia’s very openness has harmed it: “On the bigger scale and over many years, Estonia’s economic model and its institutional setup have served rather well…Unfortunately, the dependency on international linkages has turned against our favour and created most of the headwinds over the past couple of years.”

In addition, he says, the challenge of climate change and the green transition – especially the price and sufficiency of energy, electricity in particular – has also dented the economy.

“It must be admitted that investments into new electricity plants have lagged behind for a long time in Estonia and it has taken a toll in the form of a high and volatile price level,” Kattai pointed out to bne IntelliNews.

He argues, nevertheless that the model is not broken.

“The economic environment has changed, and everyone must adjust to the new reality. It is challenging, but not impossible...But the basic foundations for getting back on our feet are still there – the labour market proves to be resilient and flexible; companies are looking for new markets and possibilities, enhance technologies, productivity et cetera,” he says.

President Karis also believes no major rethink is needed: “I do not believe so. The things that have brought us success like business freedom, the digital economy, a simple tax system and a superior education system are still functioning and important for the economy to succeed.”

But for some Estonian entrepreneurs the picture seems much gloomier. Uve (not his real name) says the Russian invasion of nearby Ukraine has had a big impact. He says US investment in business and innovation, which had been the backbone of much of the country, has dried up as sentiment turned.

He also points to the impact of switching the economy away from its heavy dependence on Russian gas, electricity, timber and other supplies, as well as the price-tag of the country’s much beefed-up defence against the Russian bear.

This year, Estonia's defence spending is expected to total 3.43% of GDP, well above the alliance's 2% guideline, and could go even higher in the future. For Estonia, the enhanced defence comes at the expense of a bigger hole in the budget.

“As a result, taxes are increasing and will be increasing significantly, which means that many IT companies and startups will leave the market either to Latvia or Lithuania,” Uve told bne IntelliNews.

“Estonians are very calm and humble people with a difficult history, and despite the troubled times, they continue to live their calm lives. But businessmen are already actively migrating, leaving Estonia – quietly,” Uve says.

Despite the long recession the government managed to win re-election last year, but this has only magnified its subsequent problems.

“It is hard to say that any concrete decisions went wrong, but the biggest issue was dishonesty,” Tonis Saarts, Associate Professor of Comparative Politics at Tallinn University, told bne IntelliNews. “Prime Minister Kaja Kallas and her Reform Party chose not to talk about the catastrophic budget deficit before the 2023 elections and promised not to raise taxes. Ultimately, her government did the opposite, and many voters felt cheated.”

He notes that the dismal economic record of the coalition has boosted some but not all of the opposition parties.

“We see the rise of the opposition party, Pro Patria (Isamaa), which is the most popular party in Estonia right now. Interestingly, the current crisis has not contributed to the popularity of the populist radical right (EKRE), mostly because of their own strategic and tactical mistakes and enhanced radicalism, which has not proven to be so attractive to a lot of moderate conservative voters,” the analyst says.

In a recent poll by Norstat, Isamaa polled at 29.9%, SDE at 17.4% and the Reform Party at 16.6%, with EKRE at 12.8% and the Centre Party at 12.6%.

Politically, the current coalition parties — Reform Party, Social Democratic Party (SDE), and Estonia 200 — are unlikely to face immediate consequences for their policies, given that the next elections are still far off.

“The next parliamentary elections are still almost three years away, providing ample time for potential short-term issues to be overshadowed or for the government to shift blame. This situation enables them to continue their current course without immediate repercussions, despite potential long-term economic challenges,” says Korobeinik of the Centre Party MP.

The Reform party and some of its key MPs did not answer bne IntelliNews queries.

Is there a glimmer of hope ahead for Estonia?

“Although Estonia has witnessed a prolonged decline in GDP, the overall economic situation seems to remain solid,” says President Karis. “Household incomes are still growing and the increase in unemployment has been less than expected. However, it seems that the conditions have been getting better for the economic growth in recent quarters and we should see some recovery in the near term.”

Kattai of the central bank says: “The most recent data shows that there was a faint pick-up in economic activity in the second quarter of this year – by that measure the prolonged recession has come to an end by now. However, this time the recovery is going to be slower than in the earlier occasions.”

Another battle that Estonia must fight now, he says, is to get fiscal discipline back on track.

“It means reduction in the budget deficit and therefore less support for economic activity. The recently renewed coalition agreement between the government parties plans to contract public expenditures and increase tax rates and although it hampers the speed of economic recovery in the short term, it is crucial for putting stop to the increasing public debt and supporting economic growth in the longer perspective,” Kattai emphasised.

Raudsepp’s forecast is far gloomier: “Tax increases at the beginning of 2024 accelerated inflation and prolonged the recession in Estonia. Now the government plans to repeat the same in 2025. The crisis in our economy will continue for a long time.”

Features

BEYOND THE BOSPORUS: Investigators feel collar of former Turkish central bank deputy governor

Regime gangs continue to hustle for gains. Some Erdoganist businessmen among the losers.

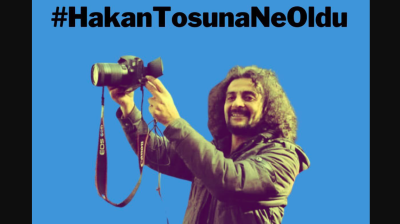

Journalist beaten to death in Istanbul as security conditions in Turkey rapidly deteriorate

Publisher, meanwhile, is shot in leg. Reporters regularly experience violence, judicial harassment and media lynching.

Agentic AI becomes South Korea’s next big tech battleground

As countries race to define their roles in the AI era, South Korea's tech giants are now embracing “agentic AI”, a next-generation form of AI that acts autonomously to complete goals, not just respond to commands.

Iran's capital Tehran showcases new "Virgin Mary" Metro station

Tehran's new Maryam metro station honours Virgin Mary with architecture blending Armenian and Iranian design elements in new push by Islamic Republic

_Cropped_1.jpg)