The EU is gearing up to introduce a thirteenth package of sanctions against Russia that could be in place in time for the second anniversary of the start of the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24.

The EU passed a twelfth sanctions package in December that included bans on trading in Russian diamonds and introduced new restrictions on imports of things like aluminium wire.

However, the main thrust of the most recent sanctions packages has not been to introduce new bans on product and services, but rather to make the existing eleven rounds of sanctions work better.

As bne IntelliNews has reported, the sanctions programme against Russia has largely failed as the Kremlin has successfully worked out ways to avoid the restrictions by trading with intermediaries in third “friendly countries.”

The Financial Times reported that not a single barrel of Russian crude oil has been sold below the oil price cap of $60 and oil sanctions are a spent cannon. At the same time Russia has almost entirely avoided the technology sanctions and has imported more technology during the war than it did pre-war.

The sanctions were supposed to drain Kremlin funds and make it impossible to fund the war in Ukraine, but the preliminary results from 2023 show that Russia’s tax revenues have also recovered to pre-war levels. Russia’s current account surplus in 2023 will come in at around $55bn, about half the pre-war result of $120bn, but experts say that significant amounts of profits earned from Russia’s now extremely opaque oil exports are not returning to Russia and building up in an offshore slush fund estimated to be already worth some $140bn.

In keeping with the twelfth package, the thirteenth sanctions package will noticeably not be some of the few things that the rest of the world is still forced to buy from Russia and can’t be sourced elsewhere. The new package reportedly excludes additional restrictions on Russian nuclear fuel.

While several other countries, including Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, also have significant deposits of uranium, Russia dominates the global refining of uranium into the so-called “yellow cake” U235 isotope used by nuclear reactors, accounting for half the world’s global output. Processing in Central Asia is minimal.

Even the US is heavily dependent on imports of Russian yellow cake to run its extensive fleet of nuclear reactors and admitted in comments last year that it would take up to five years to wean itself off Russian U235 supplies. However, in more recent contradictory statements, some lawmakers in Congress have called for a ban on Russian uranium imports.

Russia’s nuclear exports are booming as countries in the global south turn to Russia for reactors to solve widespread energy shortages in their fast growing economies. Russian nuclear power plants (NPP) are very appealing as the Kremlin typically finances up to 80% of the cost of building them, but the deal comes with 60-year uranium supply and maintenance deals that make the purchaser heavily dependent on the Kremlin. For the Kremlin, nuclear technology is becoming the new gas in geopolitically charged energy deals that unlike gas have global reach.

South Africa in particular, has become a firm Russian ally in its showdown with the West, but is also in the process of commissioning a Russian nuclear power station that is hoped to solve its chronic shortage of power. Half a dozen other African nations are in talks with Rosatom, the Russian nuclear national champion, on similar deals and a NPP in Egypt is already under construction.

The rest of the sanctions package is designed to further “improve” the West’s ability to close trade routes and prevent the circumvention of existing sanctions.

In one recent success, since the end of December, Turkish banks began to sever relations with Russian counterparties. Turkey has become one of Russia’s most useful allies by refusing to impose Western sanctions and facilitating a huge amount of both trade and financial flows via its banks.

However, that has changed after the US threatened to impose second sanctions on banks that facilitate “eventual” transactions with Russian banks in December. Under previous SWIFT sanctions that were imposed only days after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February, Western banks were prohibited from doing business directly with Russian banks.

However, in December the US threatened to impose secondary sanctions on banks that were part of a daisy-chain of intermediaries where money eventually ends up in Russia. The upshot is that the onus on investigating if a financial transaction busts sanctions or not has shifted from the US Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) to the compliance departments of banks and many have simply chosen to cut off suspect customers rather than run the risk of potential huge US-imposed fines should a counterparty transpire to be part of a Russian daisy-chain.

In the last month, Turkish banks have chosen to sever correspondent relationships with Russian partner banks, in some cases officially, and in others in the form of suspension of payment processing without formal closure of contracts, Russia’s Kommersant reported on January 17, with the exception of subsidiary foreign banks in Russia. Employees of logistics companies working with Turkey told Kommersant that cross-border payments have become dramatically more difficult. The problems with making payments is expected to have a knock-on effect and drastically reduce Turkey’s trade with Russia, unless bankers can find a new loophole to dodge the new impediments.

The thirteenth package of sanctions is also intended to find ways to curb EU imports of Indian refined oil products that have their origin in Russia.

Since the EU imposed twin oil sanctions on December 5 2022 and February 5, 2023, banning the direct sale of both Russian crude and refined oil products to the EU, the Kremlin has successfully redirected its entire export volumes to new customers in Asia, mostly India and China. However, once Russian crude is refined in Indian refineries, it is shipped back and sold in Europe as “Indian oil products”, gutting the effectiveness of the bans.

A report from Polish Radio in Brussels highlights that while the EU is preparing for stricter measures against Russia, oil imports from India to the EU have reached record levels. Delhi's imports of Russian crude oil reportedly surged by more than 100% in 2023 and 20 out of the 27 EU member states have been buying Russian oil via India.

However, the debate over the details of the thirteenth package are likely to be protracted and difficult. While the European Commission (EC) executive, led by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, is adamant that extreme sanctions should be used to bring Russia to its knees, EU member states have tempered their enthusiasm for sanctions by balancing them against the damage they do to their economies thanks to a boomerang effect. Hungary and Austria, for example, remain heavily dependent on the import of Russian oil and gas with few alternative sources of supply and have resisted almost all of the sanctions imposed so far.

One item that has not appeared at all in the proposals for the thirteenth sanctions package is bans on the import of LNG from Russia. After Russian piped gas deliveries to the EU were drastically curtained in 2022 after the Nord Stream 1&2 pipelines were destroyed, the EU imported a whopping 130bcm of LNG, almost as much as previously arrived from Russia by pipeline. However over a tenth of that LNG came from Russia and LNG deliveries to Europe have soared as the Kremlin gradually replaces piped gas with its supercooled alternative. Last year half of Russia’s LNG sales were to the EU. Still a relatively immature business, the EU has been reluctant to even consider banning Russian LNG supplies as the global supply of LNG is still too small to meet all of Europe and Asia's demand. Having overpaid €185bn for gas in 2022 during the energy crisis, according to one estimate, the EU is keen to avoid triggering a fresh gas shortage crisis by cutting itself off from Russian LNG until it has found an alternative source of energy.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) reported last week in its annual report that “massive” gains have been made with the roll out of new renewable energy capacity, but the EU is still a long way away from being able to replace fossil fuel sources of energy with green energy. The IEA said in its report that despite the gains, the pace of rolling out more renewable generating capacity this year still needs to accelerate again.

News

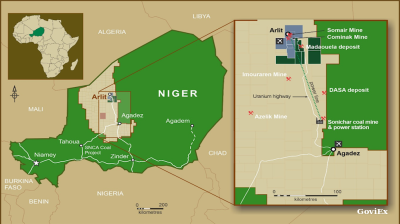

GoviEx, Niger extend arbitration pause on Madaouela uranium project valued at $376mn

Madaouela is among the world’s largest uranium resources, with measured and indicated resources of 100mn pounds of U₃O₈ and a post-tax net present value of $376mn at a uranium price of $80 per pound.

Brazil’s Supreme Court jails Bolsonaro for 27 years over coup plot

Brazil’s Supreme Court has sentenced former president Jair Bolsonaro to 27 years and three months in prison after convicting him of attempting to overturn the result of the country’s 2022 election.

Iran cleric says disputed islands belong to Tehran, not UAE

Iran's Friday prayer leader reaffirms claim to disputed UAE islands whilst warning against Hezbollah disarmament as threat to Islamic world security.

Kremlin puts Russia-Ukraine ceasefire talks on hold

\Negotiation channels between Russia and Ukraine remain formally open but the Kremlin has put talks on hold, as prospects for renewed diplomatic engagement appear remote. Presidential spokesman Dmitry Peskov said on September 12, Vedomosti reports.