What and where is Transnistria?

A small separatist republic within Moldova, Transnistria is a long, thin stretch of land between the Dniester river and Moldova’s border with Ukraine.

A secessionist movement emerged in the final years of the Soviet Union, a time when Moldovan politicians were talking of unification with Romania – anathema to the mainly ethnic Russian population of Transnistria. After a civil war that ended in July 1992, the self-declared republic, which calls itself the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic (PMR), has been de facto independent since the early 1990s, and has political, economic and military backing from Russia, though neither Russia nor any other state has formally recognised it as independent.

Why is it in the news now?

There has been speculation that – as a Russia-backed territory on Ukraine’s western flank, with Russian troops stationed in it – Transnistria could be used to open a fourth front in the war in Ukraine.

This was fuelled by a video of Belarusian President Aleksandr Lukashenko with a battle map that went viral on social media. The map appeared to indicate Moldova was part of Russia’s invasion plans, as an arrow pointed from the Ukrainian port city of Odesa into Transnistria. Odesa is less than 100 km from Transnistria’s capital Tiraspol, so if Russian forces take Odesa, they could push on to Transnistria and link up with the troops there.

Is Transnistria likely to be used to attack Ukraine or Moldova?

Not very. The Russian military presence in Transnistria is very small with only around 1,400 soldiers, compared to the tens of thousands that have entered Ukraine from Russia and Belarus.

When it comes to speculation about an attack on Moldova, it’s important to point out that Moldova, unlike Ukraine, has declared its neutrality and has not voiced any ambitions to join Nato.

The Moldovan government has said since the outset that there have been no signs of preparations for an attack on either side from Transnistria.

Having said that, since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, citizens of countries across Central and Southeast Europe have been wondering fearfully where may become Russia’s next target. There has been a shift in how Russian President Vladimir Putin is perceived from ruthless but rational leader to terrifyingly unpredictable despot. So nothing is ruled out.

Should Putin decide to attack, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken said on March 6 that the US will provide Moldova with the same support it provides to Ukraine if confronted with Russian aggression – ie. lots of verbal and sanctions support, but stopping short of entering a war with Russia.

What is the government of Transnistria saying?

Officials in Tiraspol have been pretty quiet since the invasion. They only broke their silence on March 4, after the Moldovan government announced it had submitted a formal application for EU membership. That didn’t go down well in Tiraspol, which issued a statement reasserting its independence and saying the request ignored the negotiations aimed at reaching a settlement to the Transnistria conflict.

Who’s in charge in Tiraspol?

Sheriff. No, not a sheriff, Sheriff Holdings, the huge conglomerate founded by former Soviet special services officers Viktor Gushan and Ilya Kazmaly.

Sheriff supported President Vadim Krasnoselski, and since the 2020 general election it has controlled virtually all the seats in Transnistria’s parliament, most of which are held by members of the Sheriff-backed Obnovlenie (Renewal) Party.

Aside from the government, Sheriff’s assets include the Sheriff supermarket chain, Sheriff petrol stations, construction companies, a TV channel, a publishing company and the $200mn football stadium in Tiraspol that hosts the highly successful FC Sheriff Tiraspol football team. In 2021, FC Sheriff became the first Moldovan team to reach the group stages of the UEFA Champions League and scored a shock victory over Real Madrid. Its manager Yuriy Vernydub was last seen in army uniform in Ukraine, preparing to fight the Russian invasion.

What’s it like there?

Perhaps the best indicator of what life is like is that Transnistrians have voted with their feet; the population has dropped by almost half from 679,000 in 1989 to an estimated 347,251 as of 2021.

Aside from that, Transnistria is visibly very different from the rest of Moldova, as it retains many of the symbols of the old Soviet Union, with statues of Lenin still standing and a hammer and sickle on the national flag. The republic's small size and dubious international status have kept the international companies present elsewhere in the region away.

What’s the economy based on?

Transnistria profits from free Russian gas, smuggling and one of Europe’s largest textiles factories.

The rebel republic effectively gets Russian gas for free as the gas is delivered there but the bill is sent to Chisinau; as of 2021 there was an outstanding debt of $7bn. The gas is burnt at the Cuciurgan power station controlled by Russia’s Inter RAO, and the cheap electricity has enabled a lucrative crypto-mining industry to emerge.

Smuggling used to be big business too, but less so since the authorities in both Moldova and Ukraine tightened border security.

Meanwhile, agricultural and manufacturing companies in Transnistria have benefited from Moldova’s Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA) deal with the EU that has allowed Transnistrian firms to reorientate their exports westwards.

What use is Transnistria to Moscow?

Russia’s actions in Transnistria are typical of the divide and rule playbook also used in other post-Soviet republics Georgia and Ukraine. Initially, Moscow’s backing for the separatists ensured that Moldova wouldn’t be able to unite with Romania. Ever since then, Russia has been assured of a say in whatever happens in Moldova thanks to its position in Transnistria.

Will the conflict ever be resolved?

Negotiations have been ongoing for years in the 5+2 format (Moldova and Transnistria, plus Russia, Ukraine and the OSCE as mediators, and the US and EU as observers) in an attempt to reach a peace settlement, but any progress in the talks has tended to be on specific issues such as movement of citizens and trade, rather than the fundamental question of whether Transnistria will ever rejoin Moldova and if so on what terms.

Features

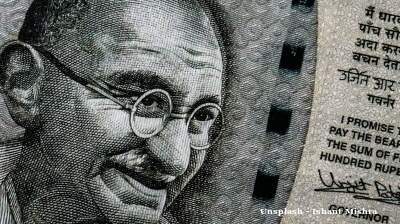

Indian bank deposits to grow steadily in FY26 amid liquidity boost

Deposit growth at Indian banks is projected to remain adequate in FY2025-26, supported by an improved liquidity environment and regulatory measures that are expected to sustain credit expansion of 11–12%

What Central Asia wants out of the upcoming Washington summit

Clarity on critical minerals and a lot else.

Global leaders gather in Gyeongju to shape APEC cooperation

Global leaders are arriving in Gyeongju, the cultural hub of North Gyeongsang Province, as South Korea hosts the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation summit. Delegates from 21 member economies are expected to discuss trade, technology and security.

Project Matador marks new South Korea-US nuclear collaboration

Fermi America, a private energy developer in the United States, is moving ahead with what could become one of the most significant privately financed clean energy projects globally.