In a small house in eastern Ukraine, fighters gather. A dozen men wander about the building – one man cleaning his rifle, another taking a quick nap, two others grilling meat on a small barbecue in the yard. The scene is similar to hundreds of other near-frontline positions in the Donbas, where Ukrainian defenders battle to hold off the ponderous Russian offensive ongoing for several months now.

There are a few signs, though, that reveal that this unit is a bit different from your average Ukrainian platoon. Most of the men are clearly not Slavic, possessing decidedly foreign facial features and the shorter frames of mountain folk. The flags that adorn the walls are a clearer hint: a series of red and white stripes on a green background, with an ornate black wolf symbol in the centre.

This is the flag of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, the separatist state that existed in the 1990s prior to its reconquest by Russia at the start of Vladimir Putin’s rule. Now, several thousand pro-independence Chechen fighters have raised the banner again, fighting alongside Ukrainian troops against Russia’s forces.

This particular unit is the Dzhokhar Dudayev Battalion – named in honour of the first president of Ichkeria, killed by Russian forces in 1996 during the First Chechen War. Formed in response to the initial fighting in Donbas in 2014, the group is now engaged in the defence of Bakhmut, the city that has become the centrepiece of Ukraine’s resistance in recent months.

“We’re doing reconnaissance work these days,” says Maga, a 30-year-old fighter in the group. “We’re looking at the enemy positions and helping other units to destroy them, whether with artillery, small raids or whatever else. There are about 50 of us in this detachment [doing this work],” he says.

The battalion is presently operating in the fields and treelines around Bakhmut, outside the city itself. Another Chechen unit, the Sheikh Mansur Battalion – named after an 18th century anti-Russian Chechen leader – is deployed in the city centre, facing down waves of Russian assaults. “They got the hard assignment this time,” Maga says with a smile.

Intense urban battles are something new for Ukrainian troops, something they got a taste of in 2014 but never experienced fully. They are not new for the Chechens.

As the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, Chechnya declared its independence but Moscow refused to accept its secession. On New Year’s Eve 1994, the Russian armed forces – at the direction of then-president Boris Yeltsin – launched a full-scale assault to reconquer Chechnya.

Miraculously, the Chechens not only held out for two years but scored a stunning victory, defeating the far larger Russian army and forcing Moscow to accept their de facto independence. But it would not last.

Shortly after Vladimir Putin was appointed Yeltsin’s successor in late 1999, he launched the Second Chechen War. This time Russia took no chances. They pummelled the Chechen capital, Grozny, into ruins with artillery and air strikes before capturing it, and spent the rest of the 2000s brutally eradicating the Chechen fighters who fled to the forests and mountains.

Today, Chechnya is ruled by Ramzan Kadyrov, a ruthless warlord personally appointed by Putin, who has sent many of his own fighters to support Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Chechen echoes in Ukraine

Maga lived through all of this. Born in Grozny in 1993, he witnessed two wars before his eighth birthday.

“I lived in Grozny until I was seven,” Maga says. “I was a child, but I watched the Russians doing their ‘cleansing’ operations, rounding up and arresting anyone they want. I remember my grandparents taking me away to the countryside when [the Russians] would come to our neighbourhood,” he says.

Maga’s father was a commander in the Chechen wars, leading fighters on the south-west front there. That meant they couldn’t stay once Russian troops captured Grozny. The family fled to France, with Maga finishing his schooling there before making his way to Ukraine in 2016. He began military training and joined the Dzhokhar Dudayev Battalion in 2019.

He sees the echoes of Russia’s war on his homeland in their current campaign in Ukraine.

“A lot of things [Russia] is doing in Ukraine, they were doing back in Chechnya,” Maga says. “The same torture, the same mass graves. They just come and destroy everyone who could be against the regime they want to create. Nothing really changed in Russia since the war in Chechnya,” he says.

His own people having born witness to the brutal, imperial nature of modern Russia for decades, Maga struggles to understand how it took the rest of the world so long to recognise it.

“Sometimes, the reaction of Western countries – Europe, USA – shocks me,” Maga says. “The logic of the West is, if it doesn’t touch them, it’s an internal problem of Russia. [The first president of Ichkeria] Dudayev said that if you let Chechnya be an ‘internal problem,’ then next the rest of the former Soviet Union and then Europe itself will be an ‘internal problem’ of Russia. It’s so easy to understand that I can’t believe people didn’t get it,” he says.

Chechnya itself has meanwhile become a key source of manpower for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – a grim irony, given its recent history. Maga has found himself face to face with his own countrymen on the other side of the line more than once.

“There are thousands of Kadyrovtsy here,” Maga says, using the common term for fighters who answer to Kadyrov. “The only way to earn a living in Chechnya today is to work for the state. They have created a situation there where you must obey the ruler at all costs, and that includes going to war for him,” he says.

While the core of the Dudayev Battalion is ethnic Chechens, there are other nationalities represented as well. Alexander, a 43-year-old former construction worker, is one such. An ethnic Ukrainian, he became acquainted with a number of Chechens in previous years through scratch football games, leading him to learn more about their wars with Russia – and just how similar the Chechen struggle is to Ukraine’s own.

“When the Chechen wars were happening [in the 1990s], we were still being brainwashed,” Alexander says. “We were told on TV all day long, especially on Russian channels, that Chechens were terrorists, enemies. We didn’t have the internet or other sources to assess it critically. But once I started to read more, to learn about it, I can compare exactly what happened there [Chechnya] to our situation here,” he says.

Alexander joined the Dudayev Battalion on February 24 last year – like many Ukrainian men at that time, he went to a volunteer unit after seeing the bureaucracy involved with enrolling in the army.

Both Maga and Alexander also agree that the impression of Chechens among Ukrainians is becoming more positive in general. The visibility of Chechen units fighting alongside Ukrainian soldiers in Bakhmut and elsewhere has corrected the previous impression that most Chechens are simply Kadyrov’s forces.

For Alexander, the time spent alongside his Chechen comrades now means that for him, the war will not end with the expulsion of Russian troops from Ukrainian territory – but with the liberation of Chechnya itself.

“As long as I am still alive, I will participate for sure [in the liberation of Chechnya],” Alexander says. “Why? Because for me, they [Chechens] are a brotherly people. I adopted a lot from them: the way they relate to life and death, the respect they have for their elders. They help us effectively, calmly, fearlessly. And after our victory, I am sure that many of our guys [Ukrainians] will go to liberate Chechnya as well,” he says.

As the rest of his squad begins to suit up for the day’s mission, Maga has a few final words about his own intentions after the liberation of all of Ukraine.

“We’ll come back to Chechnya – to Ichkeria, of course,” he says. “We’ll march straight through Russia if we have to. And we will drag Kadyrov from his throne.”

Features

Is AI making us less intelligent? The debate over declining cognitive skills in the age of ChatGPT and smartphones

Anecdotal evidence from educators paints a troubling picture. Teenagers across the world struggle to properly complete tasks in school, particularly those involving writing.

BEYOND THE BOSPORUS: Arm of state bags itself a crypto exchange

Following claims of money laundering, Icrypex becomes the latest of hundreds of companies to be seized by Turkish regime’s TMSF.

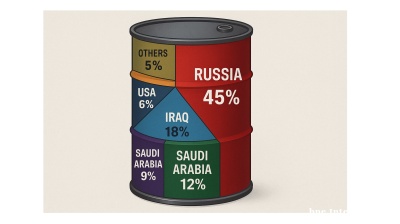

Kazakhstan reviews its big oil contracts looking for a better deal

COMMENT: Kazakhstan is reviewing its big oil contracts Kazakhstan has begun laying the groundwork for a revision of the contracts it signed with big oil in the 1990s when the country was flat on its back.

Can India dump Russian oil imports completely if Trump’s secondary sanctions appear?

Since early 2024 India has typically bought 1.5–2.0 mbpd of Russian crude, or about 35–40% of its total imports. US President Donald Trump is threatening crushing 100% tariffs on Russia’s business partners if they continue to import crude.