The Russian Federation has defaulted on its debts, failing to pay interest on a pair of Eurobonds within their 30-day grace period that ended on 26 June. While the International Swap & Derivatives Association’s Determinations Committee found Russia already to be in default on June 9 and it had selectively defaulted on foreign holders of local debt in the early days of the war, its latest failure to pay is undoubtedly the most significant.

Escalation of Russia’s other debts is anticipated, and a barrage of legal claims are set to be launched against the Putin regime, which now must bear the ignominy of plunging the country into a redux of one of the darkest periods of the 1990s.

The default marks a victory for the West’s strategy of expanding its economic war against the Kremlin in response to Vladimir Putin’s widespread attack against Ukraine on February 24. It is important to note that Putin has been attacking Ukraine continuously since Kyiv’s Euromaidan Revolution (also known as the Revolution of Dignity) in February 2014 and that the West launched forays against the Russian economy subsequently, but that when Putin decided to launch an all-out war against Ukraine’s nationhood, the West united to do the same against the Russian economy.

Washington’s blacklisting of Russia’s Central Bank on February 28 ultimately led directly to Russia’s state of default, even if it took a few tweaks from the US Treasury along the way. But this merely marks a victory in the first key battle of the economic war against Russia.

The Kremlin’s defeat on this front will not have a material impact on its ability to wage war against Ukrainians, however. Nor will it in itself be disastrous for the Russian economy imminently, with the state buoyed by record current account surpluses caused by spiking hydrocarbon prices since the war began. In other words, dollars are still flowing into its coffers.

The default battle may be won, but it is only the beginning of the economic war against Russia.

Putin’s decision to turn his political-economic system from an autocratic one to an autarkic one means that he has little concern for the long-lasting closure of Russian access to Western financial markets, even as Beijing appears unwilling to provide him with a significant alternative line of credit for now.

And while it is true that we may well see more griping from officials in the Central Bank and Ministry of Finance – inclined to economic-liberalism and whose dour outlook has proved difficult to disguise despite their best efforts to keep lockstep with Kremlin propaganda – it will make zero difference; nor will the fact that the number of Russians living under the poverty line, which already rose by more than 69% in the first quarter of the year, is set to climb further, as is unemployment. The Russian economy and its institutions are run for the benefit of the Kremlin and the Kremlin alone.

It is a recognition of this fact that has driven the West to directly target the Russian economy to such a degree, and to seek to reduce the Kremlin’s state capacity to fund, wage and supply its war machine. And while that juggernaut was defeated on the outskirts of Kyiv and in northern Ukraine’s Chernihiv and Sumy regions on April 1, forced into retreating as its Russian lines were overstretched, its May capture of Mariupol and June seizure of Severodonetsk demonstrates that Putin’s will to wage a brutal and destructive conflict remains unchanged.

There is no serious Western voice who has argued that Russia defaulting would collapse its war machine, or that it would shake the fundaments of Putin’s political stability. Nor have there been declarations that the record cost and amount of arms that the West has been shipping to Ukraine since February will firmly turn the tide on the battlefield and see the Russians forced into a retreat. The West appears to recognise that no amount of military support is going to change this reality. But as Ukrainians fight a war of national salvation for their survival, the hope that Putin’s system can be defeated largely rests on winning the economic war against Russia.

There is also a recognition that this must go far beyond Russia falling into default. The United States, United Kingdom and European Union are all therefore taking extensive measures along four other fronts: the oil market, gas market, ruble convertibility and Russia’s connections to global supply chains.

It is important to note that the strategies applied to each segment overlap, certain tactics cut across various fronts, as do Russia’s own counteroffensives to mitigate their impact, for example Russia’s gas-for-rubles demand that has aimed to ensure that ruble convertibility cannot be entirely curtailed, or the G7’s recent suggestion to bar Russian gold from their markets. Though Russia is not a significant exporter of gold to the West, making its gold untradeable in Western markets will decrease its attractiveness to other markets, and also undermine its potential as a trade instrument.

However, unlike the sanctioning of Russia’s central bank, its debt and Moscow’s subsequent default, attacks on these fronts have far greater costs for the West – and Russia has a significant ability to raise them further. This explain why, during the G7’s meetings on June 26 and 27 in the Bavarian Alps, few new concrete measures were announced.

Although earlier this month the European Union moved to transition away from Russian oil in its latest sanctions package, and Washington banned such imports back in March, the most wide-reaching proposals have thus far fallen by the wayside. The United Kingdom and EU have refused to ban the shipping of Russian gas, which would be necessary to frustrate the Kremlin’s ability to target alternative markets.

Although sanctions mean that a dollar, or a euro, loses value as soon as it passes through Russia, the Kremlin has been able to protect ruble convertibility through its aforementioned rubles-for-gas demands even while simultaneously raising the cost of gas for Europe and selectively cutting off EU member states that do not comply with its demands.

No major loopholes have emerged to the technology sanctions imposed on Russia thus far – even Washington’s commercial bête-noire, Huawei, has been shuttering offices and cutting back on its Russia business as a result – but the incentive for firms from third countries that do not comply with the Western-led sanctions regime to find loopholes will only grow. They are already enabling other get-arounds that mitigate the impact on Russia, perhaps most notably China’s surging alumina exports to supply Russia’s sanctions-wracked metals industry. However, attempting to clamp down on that trade would risk renewed tumult in the sector, as seen in the spiralling price for aluminium when Rusal fell under sanctions in 2018.

Any action on these fronts will have major costs for the West. The rising hydrocarbon prices resulting from the move away from Moscow are being keenly felt in pocketbooks from Tacoma to Tallinn. One would be remiss not to note how difficult it is proving to agree which costs should be borne by whom, and when, even as G7 leaders proclaim lasting unity.

The fight for victory on all these other four fronts will be far more difficult than it was to push the Kremlin towards default. However, the reward from successfully doing so has the potential to be far greater. Shutting Russia off from global hydrocarbon markets to the furthest extent possible, making its currency as worthless as North Korea’s and ensuring that it cannot source alternatives to now-sanctioned Western chips and other technologies through backdoors such as Turkey and China offers the promise of dragging Putin’s war machine to a halt. At the moment, nothing else does.

Maximilian Hess is head of political risk and a foreign policy analyst based in London. He also serves as a fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Follow him on twitter at @zakavkaza

Opinion

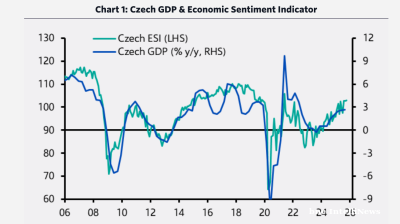

COMMENT: Czechia economy powering ahead, Hungary’s economy stalls

Early third-quarter GDP figures from Central Europe point to a growing divergence between the region’s two largest economies outside Poland, with Czechia accelerating its recovery while Hungary continues to struggle.

COMMENT: EU's LNG import ban won’t break Russia, but it will render the sector’s further growth fiendishly hard

The European Union’s nineteenth sanctions package against Russia marks a pivotal escalation in the bloc’s energy strategy, which will impose a comprehensive ban on Russian LNG imports beginning January 1, 2027.

Western Balkan countries become emerging players in Europe’s defence efforts

The Western Balkans could play an increasingly important role in strengthening Europe’s security architecture, says a new report from the Carnegie Europe think-tank.

COMMENT: Sanctions on Rosneft and Lukoil are symbolic and won’t stop its oil exports

The Trump administration’s sanctions on Russian oil giants Rosneft and Lukoil, announced on October 22, may appear decisive at first glance, but they are not going to make a material difference to Russia’s export of oil, says Sergey Vakulenko.