The impending elections of the US President apparently can open a window for negotiations on a truce between Ukraine and Russia. This week, a series of articles appeared in the leading Western media, from which it follows that Kyiv is ready to negotiate a truce in which the occupied territories de facto (but not de jure) will be left under the control of Russia, but Ukraine will receive either a guarantee of joining Nato, or similar security guarantees.

Russia is giving signals that it will not agree to such a deal.

Thrashing out meaningful security deals for Ukraine and Russia is at the heart of the talks and finding an acceptable formula won’t be easy.

It all started with a large article in the Financial Times of October 1, which described in detail about the difficult prospects of Ukraine in the coming months amid the possible victory of Donald Trump in the United States, defeats in the Donbas and the onset of winter with new Russian missile attacks on energy infrastructure.

Russia refuses to participate in peaceful summits organised by Ukraine. At the end of September, the representative of the Foreign Ministry, Maria Zakharova, called this proposal “the next manifestation of the fraud of the Anglo-Saxons and their Ukrainian puppets”, which will “drag” the “Zelenskiy formula” unacceptable for Moscow.

More meaningfully, the official position of Russia was formulated by Vladimir Putin in early September. Then he stated that Moscow was ready to negotiate on the basis of documents partially agreed, but never signed in the spring of 2022 during the negotiations over the Istanbul peace deal.

As bne IntelliNews reported, Ukraine was inching towards a ceasefire deal at the beginning of August and even agreed on a meeting in Qatar, at which both sides were supposed to take on mutual obligations to refuse to strike energy infrastructure. But the Kursk incursion ended those efforts; Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said the negotiation card has been taken off the table shortly afterwards.

Ukraine’s partners are becoming increasingly reluctant to back its war against Russia. The Swiss peace summit held on June 16-17 was deemed a failure after half of those that voted to condemn Russia’s invasion in the UN votes failed to show up to the summit. Zelenskiy's trip to New York to sell his victory plan this month was also seen as a failure, as he left with little that he was asking for.

That was followed by a whirlwind European tour that included visiting UK Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer, French President Emmanuel Macron and Italian PM Giorgia Meloni. Zelenskiy reportedly presented his peace plan, which pledges an end to the war in 2025. One of the key meetings was with German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, who promised new air defence systems and other weapons, along with a fresh military aid package, in collaboration with other NATO partners, worth €1.4bn. However, Germany has already halved its allocations to support Ukraine to €4bn this year, and this figure will fall to €500mn for the next two years after that. Scholz also once again refused to discuss sending Germany’s powerful Taurus missiles to Kyiv.

In the same week, US House Speaker Mike Johnson said there was “no appetite” for providing Ukraine with more money, suggesting that the $61bn aid package agreed on April 20 may be the last large support deal, even if Kamala Harris becomes president.

Another item on Zelenskiy’s European agenda was to badger his partners to send the money they have already promised, as Ukraine’s deficit is growing because of the tardy payments of pledged funds by Ukraine’s international partners. Last month Ukraine received a mere $10mn in international aid.

All these problems are pushing Kyiv towards restarting talks. The international press and comments by Ukraine’s allies are suggesting that a ceasefire deal is being seriously discussed behind the scenes as Ukraine’s position rapidly deteriorates.

· In late September, Czech President Petr Pavel expressed doubts that Ukraine could regain its occupied territories, urging a realistic assessment and suggesting that some areas might remain under Russian control. Around the same time, Switzerland voiced support for China and Brazil’s peace proposals, which Ukraine viewed as pro-Russian.

· On October 1, the Financial Times reported that a ceasefire deal was possible due to Ukraine's struggles, including the potential return of Trump to power, defeats in Donbas and the onset of winter, with new Russian missile attacks on infrastructure.

· On October 4, former NATO head Jens Stoltenberg compared the situation to West Germany joining NATO without East Germany, and to Japan’s security under the US excluding the Kuril Islands.

· On October 5, the FT reported that Western diplomats were discussing the idea of "Land for NATO membership," where Ukraine would receive security guarantees but quietly allow Russian control over occupied territories, hoping for a diplomatic resolution later.

· On October 8, Bloomberg reported that Western allies had noted President Zelenskiy was becoming more flexible on ways to end the war, with Ukrainian officials acknowledging that the conflict might need a resolution soon. This issue was set for discussion at the October 12 Ramstein meeting, with NATO membership being central, though Russia remained opposed.

· On October 10, Italian media suggested that Zelenskiy might accept a truce along the current front lines in exchange for Western military guarantees and EU membership, though the article appeared to be more opinion-based than grounded on actual sources.

· On October 11, the Washington Post reported, citing Western diplomats, that Zelenskiy was more open to negotiations with Russia, despite their occupation of 20% of Ukraine.

During his whirlwind tour of Europe last week, Zelenskiy insisted that ceasefire talks were not on the agenda.

Security deals

As bne IntelliNews reported, the Istanbul peace deal collapsed largely because Ukraine’s international partners refused to offer Kyiv bilateral security deals, but former UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson promised that the West would arm Ukraine if it wanted to continue to fight.

The Istanbul agreement (the full text was published by The New York Times in June) included:

· Ukraine would not join any military alliances, including NATO;

· Russia would provide Ukraine with international security guarantees, similar to NATO's Article 5, from permanent members of the UN Security Council;

· Russia would not obstruct Ukraine’s potential EU membership;

· Ukraine would agree to a 15-year moratorium on attempting to reclaim Crimea by military force and negotiate Crimea’s status with Russia; and

· Ukraine would significantly reduce the size of its military.

But now these conditions are as unacceptable for Moscow as Ukrainian proposals for Russia outlined in Zelenskiy’s 10-point peace plan presented at the G20 summit in November 2022.

Putin's most recent ceasefire proposal includes the following key conditions:

· Ukraine must withdraw its troops from the four regions that Russia claims to have annexed – Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson and Zaporizhzhia – and acknowledge Russia’s sovereignty over them, none of which Russia’s full controls; · Kyiv must drop its ambitions to join NATO; and

· Russia would then agree to an immediate ceasefire and begin negotiations.

This proposal, however, was swiftly rejected by Ukraine, which described it as a non-serious attempt to achieve peace. Ukraine continues to demand a complete Russian withdrawal from all occupied territories, including Crimea. Western allies, including NATO, have criticised Putin's offer as one that would reward Russia's aggression by allowing it to retain control over seized territories.

But last week Zelenskiy softened his maximalist position that no talks can be held until all Russian troops leave Ukraine’s territory, including quitting the Crimea.

As bne IntelliNews reported extensively at the time, Russia’s main goal in the two rounds of diplomacy in January and February 2022 was to obtain a “legally binding ironclad guarantee that Ukraine will never join NATO.” This was rejected out of hand by US Secretary of State Antony Blinken in January, and after French President Emmanuel Macron came close to restarting the Minsk II deal but ultimately failed to find an agreement. The invasion of Ukraine occurred a few days later.

According to bne IntelliNews sources, active backchannel talks are currently ongoing and focusing on security deals that will satisfy both sides.

Some of Ukraine’s allies, including Stoltenberg in his recent interview with the FT, are suggesting a “West German” solution, where West Germany was taken into NATO following unification, but East Germany was not, as the “Article 5 demarcation line” does not have to necessarily follow national borders.

Another solution that avoids NATO membership is the Korean scenario, where Ukraine concedes its eastern territories de facto but not de jura and a DMZ is set up and policed by Ukraine’s friends. This proposal was at the heart of the Chinese 12-point peace plan suggested on the first anniversary of the start of the war.

In this scenario some, but not necessarily all, of Ukraine’s allies will have to offer Kyiv real military security guarantees and come to its aid should Russia attack again.

Getting Kyiv to give up its NATO ambitions and revert to its neutral status that was enshrined in the constitution until 2014 should not be that hard, as it already conceded this in the first months of talks with Russia in Belarus. However, this option necessitates some real security guarantees from some NATO members and not the “security assurances” it has received so far from the likes of the UK, which come with no obligation to come to Ukraine’s military aid in the event of a new Russian attack.

The West remains extremely nervous about bringing even a rump Ukraine into NATO, as it realises that this is a red line for Putin and one that he is very unlikely to allow to be crossed without responding, despite the fact he has allowed so many other red lines to be crossed.

Part of the problem is that Ukraine is a young democracy and while Zelenskiy has signed off on the EU value agenda, the case of Georgia, which was also a poster boy for liberal reform following the Rose revolution and the accent of former President Mikheil Saakashvili, stands as a warning, as it has since been entirely captured by the Russia-leaning oligarch Bidzina Ivanishvili, who is threatening to fix the general elections at the end of October to hang on to power and has already forced through several Russian-styled illiberal legislation such as a “foreign agents” law and anti-LGTBQI laws. Western powers are nervous of providing military security guarantees to countries that could slide back into authoritarianism.

And in addition to power hungry Ukrainian oligarchs, of which there are plenty, there is a more immediate threat of Ukraine’s far-right groups. Ukrainian deputy Oleksandr Merezhko, the chair of the parliament’s foreign affairs committee and a member of President Volodymyr Zelenskiy’s Servant of the People party, warned about the threat posed by what he described as a growing far-right movement in Ukrainian society in an interview with the Financial Times earlier this year. The concern is if Zelenskiy attempts a ceasefire or gives away territory there will be a possibly violent backlash from these groups with unpredictable results.

As for Russia, the no-NATO for Ukraine is paramount, but it also wants security guarantees from the West. As bne IntelliNews reported, the first thing that Dmitry Medvedev did after being elected president in 2008 was travel to Brussels and offer a new post-Cold War pan-European security deal, which was rejected out of hand. During the Istanbul talks, the Kremlin was prepared to make several key concessions. While the Crimea remains permanently off the table, the Kremlin suggested it might accept the Donbas being turned into an autonomous republic but remaining formally inside a federated Ukraine. Russia was also prepared to offer Ukraine the same security guarantees it was demanding from the West. However, the status of the two new regions annexed last autumn of Kherson and Zaporizhzhia will be a very difficult nut to crack. Russia has now incorporated them into the constitution as Russian sovereign territory, making it very difficult for the Kremlin to give them back.

The upshot is one of the most likely scenarios – the Cypriot standoff. Turkey invaded Cyprus on July 20, 1974, in response to a Greek-led coup on the island, which aimed to unify Cyprus with Greece. As with Russia, the Turkish military intervention was framed as a “peace operation” to protect Turkish Cypriots, but it resulted in the division of the island into a northern Turkish-controlled area and a southern Greek Cypriot area.

And the conflict has been frozen ever since. As of now, the northern part of Cyprus is the self-declared Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), which was proclaimed on November 15, 1983. However, the TRNC is recognised only by Turkey, while the rest of the international community considers it as part of the Republic of Cyprus. There have been various attempts to reunite the two halves without success. Kofi Annan, the former Secretary-General of the United Nations, attempted to reunite Cyprus through what became known as the Annan Plan plan in the early 2000s, but the effort ultimately came to nought.

Cyprus joined the EU on May 1, 2004, but only the Greek Cypriot-controlled southern part enjoys full EU benefits, as the northern part is not internationally recognised and Cyprus is not a member of NATO, although Turkey is. The Article 5 demarcation line does not cover Northern Cyprus.

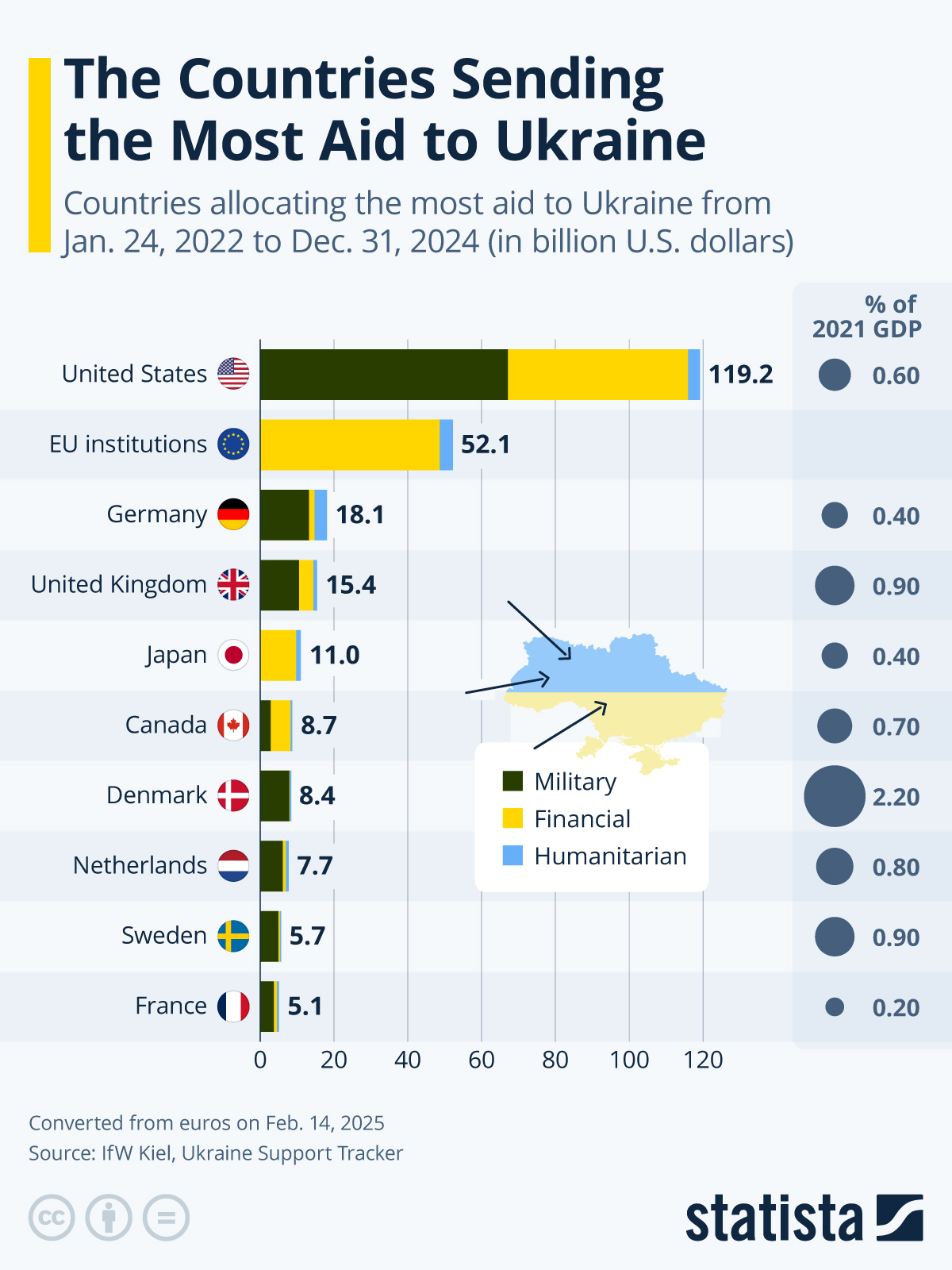

You will find more infographics at Statista

You will find more infographics at Statista