Whoever is in power after Kyrgyzstan’s presidential elections in January may have to look beyond the budget to service swelling state debt – a big chunk of which is owed to China.

The Export-Import Bank of China, which holds around $1.8bn of the $4.8bn total, is not among the creditors that have granted Bishkek fresh grace periods.

On November 16, Kyrgyz Foreign Minister Ruslan Kazakbayev held a phone conversation his Chinese counterpart, Wang Yi, in which he “drew attention to the importance of providing assistance in alleviating the burden of external debt on the country's budget.”

Kazakbayev also pledged that Kyrgyzstan would protect Chinese businesses, a vow that has assumed particular salience since several Chinese companies came under threat during the recent political unrest.

He might have saved his breath.

Prior to being ousted as president last month, Sooronbaj Jeenbekov and other top officials tried several times to persuade the Chinese to defer Kyrgyzstan’s repayments.

Former deputy prime minister Erkin Asrandiyev claimed in April that Bishkek’s request had "found understanding" in Beijing.

But China has said nothing publicly to lend credence to this impression.

Sadyr Japarov, who on November 14 resigned from his positions as head of government and acting head of state so that he could run for president, is a clear favourite for the January 10 election. He is also the latest politician to call for financial contributions from citizens to pay off the state debt, noting the debt to China in particular.

In his first and last press conference as interim leader earlier this month, Japarov said the idea was “a people’s initiative,” but he stressed that nobody would be forced to contribute.

A lawmaker known to be a Jeenbekov loyalist issued a similar call in mid-October.

Ainuruu Altybayeva said that the initiative of her Council of Women civic group would be coordinated with the Finance Ministry and that donations would be listed online to ensure transparency.

Both calls have been greeted coolly by a public jaded by decades of rampant corruption.

Prior to this year, Kyrgyzstan had done a good job of servicing its foreign debt. But the year of the coronavirus pandemic has proven particularly terrible for a landlocked nation whose economy is strongly reliant on shuttle trade with China.

Forecasters are variously predicting an economic contraction of between 8% and 10%. That has obvious implications for the bottom line.

Even Japarov, ever the populist, has resisted committing to increasing paltry salaries, which have lost purchasing power this year as the national currency, the som, has faltered against the dollar.

“Hold on for one more year,” he told police officers in the northern Naryn region at a recent ceremony to hand over keys to new accommodation.

Japarov made a similar plea to regional officials during a tour of the south.

Kyrgyzstan in June secured a Paris Club agreement to suspend servicing of $11mn worth of debt until the end of the year.

The creditor countries involved in that agreement were Denmark, France, Germany, Japan and South Korea, to whom Bishkek collectively owes over $300mn in total.

China’s policy on debt forgiveness is less flexible, as debtor states across the world can attest.

Dastan Bekeshev, a lawmaker, this month posted a helpful video rundown of how Kyrgyzstan’s debt to Beijing was accrued and on what terms.

At 2%, Exim Bank’s loans to Bishkek have grace periods ranging from five to 10 years. But most of the credits date back to agreements for transport and energy infrastructure which were struck six or more years ago.

And the rub is that any disputes over repayments are adjudicated by Chinese courts of arbitration, rather than international ones, Bekeshev noted.

Bekeshev, one of few Kyrgyz parliamentarians not boasting considerable personal wealth, noted bitterly that authorities were already saving some money by not paying parliamentary salaries.

Talant Mamytov, parliament's speaker and new acting president, said that the funds are instead going toward the repair of the White House, which acts as a parliament and presidential office and was damaged during turbulence in October.

Embracing this spirit of austerity, another lawmaker, Omurbek Bakirov, this week proposed reducing the number of judges serving at the Constitutional Court from nine to seven.

This will save the country 2.5mn som, or $30,000 per year, he noted.

Chris Rickleton is a journalist based in Almaty.

This article originally appeared here on Eurasianet.

Features

What Central Asia wants out of the upcoming Washington summit

Clarity on critical minerals and a lot else.

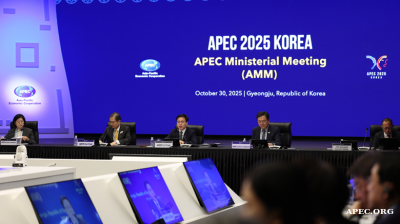

Global leaders gather in Gyeongju to shape APEC cooperation

Global leaders are arriving in Gyeongju, the cultural hub of North Gyeongsang Province, as South Korea hosts the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation summit. Delegates from 21 member economies are expected to discuss trade, technology and security.

Project Matador marks new South Korea-US nuclear collaboration

Fermi America, a private energy developer in the United States, is moving ahead with what could become one of the most significant privately financed clean energy projects globally.

.jpg)