Brazil’s recent move to block Elon Musk’s X, the popular social network formerly known as Twitter, has reignited a global debate on free speech – and its limits.

The ban, stemming from court action and upheld by a Supreme Court panel earlier this week, followed Musk’s refusal to appoint an X representative in the country and block accounts accused of spreading disinformation.

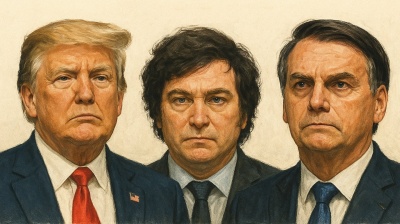

The legal saga began in April, when Supreme Court Justice Alexandre de Moraes instructed X to take down a number of accounts owned by right-wing personalities associated with former president Jair Bolsonaro. Musk initially complied but later reversed course, labelling Moraes “a dictator and a fraud, not a justice” and triggering a feud with the Brazilian government at large, accusing them of stifling free speech and censoring conservative views.

In his August 30 ruling ordering X’s ban in Brazil, Moraes lashed out at the network for being “a no man’s land – a veritable land without law” and allowing the “massive propagation of misinformation, hate speech and anti-democratic attacks”.

These words echo last month’s vitriolic plea from EU Commissioner Thierry Breton, who called on Musk to comply with the bloc’s Digital Service Act (DSA) regulation and urged X to “mitigate the amplification of harmful content”. The open letter, published on X, was sent a day before Musk's softball interview with US presidential hopeful Donald Trump. Musk hit back at Breton with a meme saying “fuck your own face”.

The EU’s DSA, which came into force in 2023 targeting “very large online platforms” with over 45mn active users, is the bloc’s first attempt at curbing big tech’s seemingly unbridled power. It aims to “govern the content moderation practices of social media platforms" and provides for fines of up to 6% of the firm’s annual turnover if found in breach of the regulation. However, it threatens a full-out ban only in case of "repeated offences," and it has never been enforced.

Brazil, which has not yet passed legislation on this specific issue, has become the world’s first democratic country to match words with deeds when it comes to limiting the spread of dangerous narratives. And for a good reason.

Moraes’ legal campaign against Musk traces back to the violent riots that sought to overturn the 2022 Brazilian presidential election, which saw President Lula narrowly win over his predecessor, Jair Bolsonaro.

In a bid to mimic the events of January 6, 2021 in the US, right-wing mobs on January 8, 2023 stormed Brasilia’s government buildings, rejecting Lula da Silva’s victory and urging the military to stage a coup to keep Bolsonaro in power. Wild theories and rumours of electoral fraud ran amok on X, where a slew of influencers and pundits closely linked to the “Trump of the Tropics” shared memes and misleading statements, which quickly went viral. Unlike in Washington, deaths were prevented when the coup attempt was thwarted, but over 300 people ended up behind bars. Bolsonaro was subsequently barred from running for office until 2030 over his peddling of lies and was officially accused of plotting a coup.

While the EU has not experienced similar violence, the rise of far-right populist parties and growing concerns about Russian-sponsored disinformation on social media present potential risks.

Look no further than across the Channel: In late July, the UK was ravaged by racially motivated riots fomented by right-wing influencers who spewed false claims about a tragic stabbing attack against children. Much of that unravelled on X, with Musk gleefully arguing that “civil war is inevitable" and criticising Prime Minister Keir Starmer, accused of discriminatory “two-tiered policing” to the detriment of right-wing protesters.

Since Musk’s $44bn takeover in late 2022, X – which defines itself as “the world’s largest town square” – has become a cesspool of disinformation and conspiracy theories, many of which are openly endorsed by its owner. Several studies have found that X’s algorithm actively promotes controversial content, driven by its murky monetisation scheme, which highly rewards viral posts and prioritises engagement over accuracy. The problem already existed with Twitter, but became massive after Musk’s acquisition. As the billionaire self-proclaimed “free speech absolutist” claims that “journalism is dying” and promotes X – which boasts over 540mn users globally – as the only truthful source of information, alarm bells should start ringing.

It is, to say the least, concerning that the world’s third-richest man believes he can be above the law and takes the liberty of meddling in different countries’ internal affairs by leveraging his own popular online platform. As President Lula laconically put it while endorsing the court’s decision, “The world is not obliged to tolerate Elon Musk’s right-wing agenda simply because he is wealthy.”

With Moraes’ bold ruling, Brazil – a developing country that is a leading member of the Global South – acted upon it and showed the world who is in charge of preserving democracy. The EU and the UK, meanwhile, watch and wait. For now, other tech platforms such as Meta and Google have been more willing to cooperate in limiting hateful and dangerous content, but that could change with the whims of new shareholders, as the case of Twitter/X has shown. Clear regulation – and the courage to enforce it – are urgently needed.

To wake up, European leaders should take a fresh look at Karl Popper’s paradox of tolerance: “Unlimited tolerance must lead to the disappearance of tolerance. If we extend unlimited tolerance even to those who are intolerant, if we are not prepared to defend a tolerant society against the onslaught of the intolerant, then the tolerant will be destroyed, and tolerance with them.”

.jpg)