Since its independence in the 1990s Moldova has struggled to remove itself from Russia’s grasp. Coerced into remaining within the so called ‘near abroad’ by a mixture of a frozen conflict in Transnistria and a Russian stranglehold on its energy supply, its EU ambitions have been repeatedly dashed.

However, the war in Ukraine has upended this status quo. Amidst the geopolitical chaos generated and which continues to be generated, Moldova has begun to take the first steps towards weaning itself from Russia’s energy blackmail.

The first step was realised on March 16, 2022 when the EU allowed Ukraine and Moldova to connect to the European grid enabling Moldova to reduce its energy dependence on Russia. Then a year ago Moldova made the unprecedented decision to not buy or import Russian gas for its energy needs. This was a pivotal moment in Moldova’s history and a clear expression of intent to escape from Moscow’s energy blackmail.

However, this rapid transition has not been without danger or pain. Even with Western assistance, buying gas from other sources increased the price of gas for Moldovan consumers seven times and sourcing the bulk of its electricity from Romania increased the price of electricity three to four times. Romanian providers simply have not been able to compete with the artificially low prices provided by the Cuciurgan plant in Transnistria which is in effect subsidised by Russia via free of charge gas from Gazprom.

The impact of these price rises on Moldovan stability should not be underestimated. Moldova is the poorest country in Europe, suffering from a high rate of corruption and emigration. This has left it particularly vulnerable to energy price rises even with Western financial assistance to compensate 40-50% of consumers. According to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 60% of Moldova’s population live in energy poverty, which is to say they spend more than 10% of their budgets on energy bills. Already Russia has weaponised this vulnerability by waging a disinformation war that aims to present the pro-Western government as buying gas from European intermediaries for the benefit of Nato and not the Moldovan people. It has also leaned on its proxy the ȘOR Party to whip up riots and mass unrest. The economically precarious position of the Moldovan population, brazen Russian interference and the rising Western fatigue for confrontation with Russia raise questions as to the durability of Moldovan efforts to reduce its energy dependence.

To assess Moldova’s chances of success one must understand two things: its Soviet energy heritage and Transnistria.

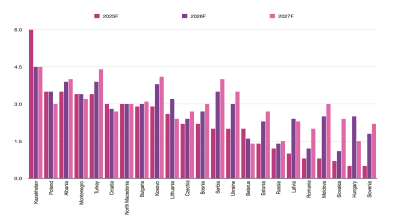

Source: Centre for Strategic and International Studies

Looking at the traditional gas pipeline routes and the newer routes constructed recently to reduce Russian imports, the majority of gas routes pass through the heart of Transnistria. These Soviet era gas pipelines are a dagger aimed at the heart of Moldovan independence. They constitute the bulk of the nation's gas infrastructure and in particular the Trans-Balkan Pipeline runs directly through Transnistria. This is the most significant pipeline in Moldova as it transports Russian gas to Southeast Europe whilst also historically serving as the conduit for the majority of the Moldovan supply.

There are also the Ungheni-Iași pipeline completed in 2014 and the Ungheni-Chișinău extension completed in 2021. Both projects were financed by the European Investment Bank (EIB) and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD). These pipelines may have helped Moldova survive the winter of 2023 but at a significant price. The problem Moldova faces is that if it continues to rely on EU gas through the Ungheni-Iași and Ungheni-Chișinău pipelines then significant price rises are likely. Prices could stabilise at around $400 to $600 per 1,000 cubic metres compared to the historical Russian price of $250-300.

Such a scenario would skyrocket household bills for the majority of the population which already lives in energy poverty. This would leave a large struggling and disaffected population as easy prey for Kremlin propaganda and grey zone operations. After all, the Russian secret services have routinely weaponised poverty in Moldova to undermine its independence and democracy. Reuters has reported that in the last month alone the Kremlin has transferred more than $15mn to buy votes and has allegedly been paying people as much as $5,500 to vandalise public buildings. This is hybrid warfare on the cheap and a permanent transition to EU gas could make such insidious tactics even more dangerous.

Moldova is aware of this danger as can be seen by the extension of its gas contract with Gazprom on October 28, 2023. In essence, the Moldovan administration is trapped in a catch 22 as when it tries to diversify its energy sources it increases the price for ordinary Moldovans making them vulnerable to Russian bribery and misinformation, but if it maintains the Trans-Balkan or Cuciurgan energy status quo then Moldova will never be truly independent. This paradox is a direct result of the nation's poisoned infrastructure inheritance which has left it dependent on Transnistria for electricity and Russia for gas.

Indeed, one could argue that Transnistria is an under-appreciated aspect to this trilemma. During the Soviet period, Moldova’s electricity was generated by the Moldavian State Regional Electric Power Plant (MGRES) situated on the left bank of the Dniester River. This placed it in Transnistria after its 1992 separation from Moldova. Subsequently, Transnistrian authorities transferred MGRES to the Russian state-owned entity Inter RAO without Moldovan consent. This transfer has allowed Russia to effectively kill two birds with one stone. It has weaponised the de facto electricity monopoly to ensure more compliant behaviour from Moldova whilst using the revenues from Moldovan purchases to prop up the local government and economy in Transnistria. In effect Moldova has and continues to pay for its own occupation, with Romanian electricity imports only constituting 15% of its total supply according to the German Economic Team, which advises governments in the region.

Pre-war the idea of cutting off Transnistria and switching to Ukrainian electricity imports was floated but ultimately it would have proven infeasible due to all the major Moldovan power lines crossing Transnistria. Post- invasion such plans are pure fantasy, with Ukraine struggling to keep its own lights on under vicious Russian bombardment. This inability to bypass Transnistria leaves Moldova stuck with a toxic mixture of Russian electricity and gas blackmail. This delicate position makes future EU-Moldovan energy and political integration exceedingly difficult. Should a pro-Russian candidate win the October 20 presidential elections then it's likely that Moldova may simply revert to gas dependency on Gazprom and electricity dependency on MGRES, ending the nations brief foray into energy sovereignty.

Despite this unfortunate circumstance Moldova is not powerless. It does have some economic leverage over Transnistria, whose main trading partners are in the EU. The bloc accounts for nearly 70% of the breakaway region’s exports and imports. Chișinău has in turn weaponised this by obliging Transnistrian exporters to pay duties through the introduction of the 2021 customs code. Were Moldova to gain energy independence or at the very least diversify significantly its energy supply these measures would massively increase its influence over the breakaway state and could perhaps convince some Transnistrian elites to compromise with Chișinău. Not least because a Moldovan abandonment of MGRES would usher in the death of the Transnistrian economy. However, such a scenario would be entirely contingent on EU support and financing.

Historically such support has been fickle. Just three years ago the EU opened infringement proceedings against Moldova for the country's failure to comply with the Third Energy Package, in particular for failing to unbundle energy companies. EU regulations mandate that the production, transmission and distribution of gas should be handled by separate entities to promote competition. This may seem mundane, but such regulatory rigidity has disguised an apathy towards providing practical aid to Moldova. It is far from clear what the EU expects of Chișinău. Whilst it is certainly true that Moldovagaz, in part owned by Gazprom, controls all three tiers it's also true that Russian vested interests align to frustrate any regulatory reforms that would undermine Moscow’s influence in the region. The reforms the EU requires would of course inevitably undermine such influence and therefore Moscow will never agree to them. Moldova could of course plough ahead with such energy reforms whilst using EU funds to purchase gas and electricity from the EU market (read Romania) but given its sluggish economic growth this would require considerable economic assistance to prevent a serious deterioration of the quality of life for ordinary Moldovans. That the EU would be willing to sponsor such an endeavour is questionable given the recent swathe of fatigue in Germany and Central Europe for supporting Ukraine and increased military spending.

So what hope is there for the dream of Moldovan energy independence? Whether Moldova gets to live as an independent state has less to do with its own inner machinations and more to do whether Europe and the wider West has the will to resist Russia. Will the Western world expend sorely needed resources and money in eroding Russia’s grasp over the post-soviet world in an era of personal deprivation for so many of its citizenry? Whatever route the West takes will make or break the incipient Moldovan energy sovereignty.

Owen Walden-Harris is a freelance journalist specialising in geopolitics, anthropology and European affairs. He has a strong interest in the practical mechanics behind political and institutional decision making having studied EU law, regulation and political theory at the College of Europe. Another facet of his work is to explore the under-appreciated role that culture plays in politics and diplomacy via the anthropological paradigm.

Opinion

COMMENT: Czechia economy powering ahead, Hungary’s economy stalls

Early third-quarter GDP figures from Central Europe point to a growing divergence between the region’s two largest economies outside Poland, with Czechia accelerating its recovery while Hungary continues to struggle.

COMMENT: EU's LNG import ban won’t break Russia, but it will render the sector’s further growth fiendishly hard

The European Union’s nineteenth sanctions package against Russia marks a pivotal escalation in the bloc’s energy strategy, which will impose a comprehensive ban on Russian LNG imports beginning January 1, 2027.

Western Balkan countries become emerging players in Europe’s defence efforts

The Western Balkans could play an increasingly important role in strengthening Europe’s security architecture, says a new report from the Carnegie Europe think-tank.

COMMENT: Sanctions on Rosneft and Lukoil are symbolic and won’t stop its oil exports

The Trump administration’s sanctions on Russian oil giants Rosneft and Lukoil, announced on October 22, may appear decisive at first glance, but they are not going to make a material difference to Russia’s export of oil, says Sergey Vakulenko.