Russia reserves gain $28bn in 2020 to reach $583bn as of November, but make-up has changed radically

_Cropped.png)

Russia’s gross international reserves (GIR) fell by about $10bn in the third quarter of 2020 as the government spent some money on alleviating the pain of the coronacrisis to reach $582.7bn as of the last day of November.

That is down from a recent high of $594.4bn at the end of August, when the economy was bouncing back nicely from the earlier pain after the lockdown was lifted.

One of the remarkable achievements of 2020 is the Central Bank of Russia (CBR) managed to add $28.3bn to its GIR in 2020 during the worst crisis in living memory that included oil prices being halved and falling into the 20s (and prices even briefly went negative at the start of the summer for the first time in history) and a deep devaluation of the ruble that touched RUB80 to the dollar at one point. Russia’s GIR on January 1, 2020 was $554.4bn, but close to $600bn at its peak in August and is now well above the CBR’s “comfort” level of $500bn set by CBR governor Elvira Nabiullina.

While the overall level of reserves has increased by 7.2% over the course of the year, which is not that big a change, the breakdown of the make-up of GIR shows some major policy decisions.

The first is that the level of reserves minus the gold holding has fallen by about $50bn from the peak at the start of the summer. Also the chart shows that since April last year the CBR has stopped buying gold, about the same time that the GIR reached Nabiullina’s comfort level of $500bn.

And finally, the government has barely touched the National Welfare Fund (NWF), which held $177.4bn as of November and has accumulated $53bn in addition to the $124.4bn it held at the start of 2020 – twice as much as the overall GIR accumulation.

There has been a fierce debate amongst Russia’s financial elite, with former Finance Minister and Audit Chamber head Alexei Kudrin arguing that the whole point of the NWF is to provide resources for when Russia is hit by one of its periodic crises and so the NWF should be tapped for stimulus spending.

Finance Minister Anton Siluanov has taken the more narrow line that the NWF is to cover budget deficits in crises, and while he does intend to use some of the money from the NWF for this purpose he has also raised the net sovereign borrowing by increasing the Russian Ministry of Finance ruble-denominated OFZ treasury bill issues from the usual circa RUB2.5 trillion ($33.8bn) to circa RUB4 trillion in 2020 to cover the deficit. This will increase Russia’s net sovereign debt from circa 14% of GDP to circa 20% of GDP, but crucially will mean that less money has to be drawn down from the NWF. The result of this decision is already clearly visible in the chart, which shows that very little money has been withdrawn from the NWF and Russia is going into 2021 with even more money in its rainy day fund than it had at the start of 2020.

In general the Kremlin has been criticised for spending too little on stimulus as the total government outlay on extra spending to fight the crisis is estimated to be a mere 3%-4% of GDP – one of the lowest levels in the world – while most developed nations are spending anything between 5% to 20% of GDP on stimulus.

The reserves chart shows clearly that Russia continues to run the same austerity policies that are designed to preserve its cash pile, which Russian President Vladimir Putin sees as a strategic weapon in the de facto economic war Russia is fighting with the US, rather than an economic resource that can be used to promote growth.

With a new Biden administration about to take over and already promising to increase the sanctions on Russia this may not be an entirely ridiculous stance to take.

-

This article is from bne IntelliNews Russia monthly country report. Sign up to receive the report to your inbox each month, which covers the slow-moving macro- and micro-economic trends, the major political news and a round-up of the main sectors and corporate news. First month is free and you can unsubscribe at any time.

This article is from bne IntelliNews Russia monthly country report. Sign up to receive the report to your inbox each month, which covers the slow-moving macro- and micro-economic trends, the major political news and a round-up of the main sectors and corporate news. First month is free and you can unsubscribe at any time.

See a sample here.

Sign up for a one-month trial here.

Question? Get in touch with sales@intellinews.com

Data

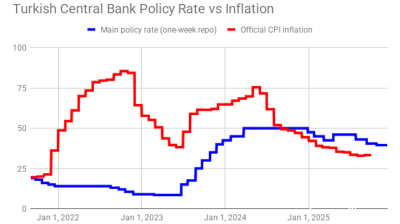

Turkey's central bank remains cautious, delivers 100bp rate cut

Decision comes on eve of next hearing in trial that could dislodge leadership of opposition CHP party.

Polish retail sales return to solid growth in September

Polish retail sales grew 6.4% year on year in constant prices in September, picking up from a 3.1% y/y rise in August, the statistics office GUS said.

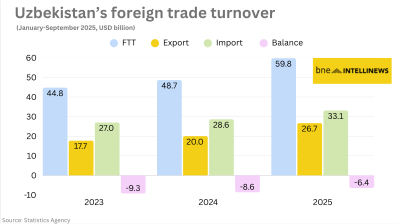

Uzbekistan’s nine-month foreign trade nears $60bn

Export growth of 33% and import expansion of 16% y/y produce $6.4bn deficit.

Hungary’s central bank leaves rates unchanged

National Bank of Hungary expects inflation to fall back into the tolerance band by early 2026, with the 3% target sustainably achievable in early 2027 under the current strict policy settings.