Russia's microchip industry is projected to grow significantly, boosted by massive government support. As microchips play a major role in Russia's war efforts in Ukraine, the focus is on ramping up production of less-advanced chips rather than becoming a high-tech player in the microelectronics market. Currently, Russia only has capabilities for producing 90-nanometre chips and is exploring mass production of 65-nm chips. Meanwhile, the US is eyeing a transition to 2-nm microchips, while China is trying to go below 10 nm.

Growth spurred by state support

Since Russia's invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, beefing up the country's microchip production capacities has been a major task for the government, as these components are vital for all kinds of contemporary warfare, from missiles to strike drones.

According to a recent report issued by Kept, formerly Russia's KPMG n division, the Russian microelectronics market is set to grow at a CAGR of 15.2% out to 2030, RUB289bn ($3.28bn) in 2023 to RUB780bn ($8.85bn) in 2030.

The main driver of growth is supposed to be government support in the forms of subsidies, loans and other incentives.

"The ministry of industry and trade annually allocates hundreds of billions of rubles for the development of microelectronics," reads the report. "Involvement of private partners would allow intensifying the development of the industry, but a more active participation of private capital requires a more transparent understanding of the conditions of return on such investments."

Start from scratch

Russia's current microelectronics industry has been built basically from scratch since the beginning of the 2010.

The Soviet-era microelectronics industry collapsed in the early 1990s, unable to compete with international manufactures when the country opened up for global imports. For almost two decades imports accounted for practically all of the country's requirement for microchips.

Currently, Russia has three plants with a capacity of produce microchips at mass scale. These are the Mikron, Angstrem and Milandr plants, all located in Zelenograd outside Moscow. Still, up until the invasion of Ukraine, Russia annually imported about $1bn worth of chips, mainly from China, Taiwan and Malaysia.

Big expectations

In October 2023, Russia's ministry of industry and trade presented a roadmap, according to which Russia would launch mass production of 28-nm microchips by 2028 and start manufacture of 14-nm microchips by 2030.

However, at this point, Russia primarily needs microelectronic components to support its war in Ukraine, and for that purpose, much less advanced 65-nm to 90-nm chips would be perfectly suitable.

Still, at the moment Russia only has capacities for mass producing 90-nm chips and is considering options for launching 65-nm chip manufacture.

The Russian government said it plans to allocate RUB100bn ($1.13bn) to boost the country's microchip capacity. And although this could be sufficient to boost production of lower-grade chips required for weapons used in Ukraine, it wouldn't bring about a tech breakthrough. According to Yakov & Partners (formerly a division of McKinsey), import substitution in the field of microchips requires investments in the vicinity of RUB400-500bn ($4.54bn-$5.67bn) up until 2030.

A race for private investment

Apparently, in a situation when Russia's state budget is stretched thin, coming up with more cash could be unrealistic.

Therefore private investment in the sector could make a difference, and the main Russian players in the microchip segment are trying to attract private cash.

"The largest players are working on various options that would be beneficial to all participants," Andrey Evdokimov, general director of Baikal Electronics Design Centre, was quoted as saying by Russian business daily Kommersant. "There are players who are ready to wait for a return on investment for ten or more years, realising the growth prospects of the industry. There are also representatives of friendly countries who can also join this initiative."

Still, he admitted that some potential private investors are reluctant to pump their cash into Russian high-tech sector in the current environment.

"It is one thing to invest in an operating system developer, which is growing here and now," he explained. "But it is a totally different thing, if you invest in a microelectronics manufacturer."

Limited capacities

Meanwhile, the main obstacle in the way of advancement in the Russian microelectronic segment is its limited production capacities.

Later this year, Russia plans to bring online its first photolithography machine for chip manufacture at one of the Zelenograd plants. The Russian state-run news agency TASS quoted deputy minister of industry and trade Vasily Shpak as saying that the first Russian lithographic scanner will have a capacity to produce microchips using the 350-nm process.

There have been reports about attempt to create a Russian photolithography machine for quite a while now. Various research institutions, including the national centre for physics and mathematics in the city of Sarov – where the Soviet atomic bomb was developed eight decades ago – the institute of microstructure physics of the Russian academy of sciences, the federal research centre of the institute of applied physics and the Kurchatov institute national research centre have all been reportedly involved in developing their own photolithographic machines. It is not clear, though, which institutions' machine is going to be launched.

In any case, the launch of the first machine certainly won't solve the issue of Russia's technological lag and the plants will have to use important lithographic equipment. Even the manufacture of Russia's Elbrus-B chip under the 65-nm process – used by Intel in the mid-2000s and now considered obsolete – requires equipment that Russia can't currently manufacture. Meanwhile, imports of such equipment to Russia are prohibited by international sanctions slapped on Russia since the invasion of Ukraine.

Currently Russia cannot manufacture its own photolithography machines for production of higher-grade chips, nor can it buy them directly from manufacturers because of sanctions. Russian officials have been talking about equipment supplied from China and Belarus. However, neither China nor the Republic of Belarus currently produce photolithographic equipment required in Russia; therefore it could be re-sale of equipment manufactured elsewhere and then supplied to Russia to avoid international sanctions.

There have also been reports claiming that the maintenance and operation of exiting photolithography machines in Russia would be impossible without input from their original manufacturers, which deny any violations of the sanctions against Russia.

More challenges ahead

Although Russia has made substantial progress in its chip industry over the last 15 years or so, it is clear that manufacture of Russian microelectronics is going to hit a number of road bumps, and the timeline presented in the roadmap by the ministry of industry and trade is hardly realistic.

Another major challenge, on top of sanctions and insufficient investment, is shortage of qualified personnel in a situation when many IT workers has left the country fearing conscription.

Overall manufacture of Russian chips is set to grow, but it will be clear over the next couple of years whether any true tech advancements will be made by the segment.

Tech

_(1).jpg)

OpenAI to invest up to $25bn in Argentina under Milei incentive scheme

Artificial intelligence giant OpenAI and energy company Sur Energy have signed a letter of intent to develop a data centre hub in Argentina requiring investment of up to $25bn.

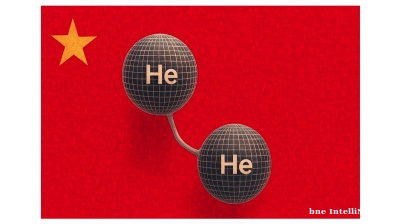

Helium was China's rare earth metals Achilles' heel

China has a devastating tool in its escalating trade war with the US: rare earth metals (REMs). Last week, Beijing announced new restrictive export controls on the export of anything with even a smidgen of Chinese-produced REMs.

Takeoff not far away for Turkey’s first flying car AirCar

It will set you back $99,000 and you'll also need a pilot's licence.

Nigeria’s CBN bans multi-operator PoS model to streamline agent banking

The Nigerian central bank's sweeping new rules require all point-of-sale (PoS) agents to operate under a single licensed provider from April 2026, ending the multi-operator model that has defined the country’s $70bn payments industry.