Climate change and the expanding global population are changing the way investors think about long-term returns. The prospect of an environmental disaster is changing public perceptions too. The population is becoming more demanding, changing they way they shop and invest. The emphasis is shifting away from making simple profits and towards sustainability. This is a slow moving change, but one with the momentum of a glacier. Governments are being forced to react. New rules are on the way that will demand investors not only consider the bottom line or return on investment (ROI), but also force them to take account of a company’s environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance.

Investors have always talked about the need for good corporate governance, but that talk is already changing to the wider concept of ESG. Corporate governance is probably the best-defined part of ESG, but the criteria used to measure the sustainability of an investment are still fluid.

“A number of very large investors — pension and insurance companies — have to make payments in the very long-term in the future and in that context they want people who manage money and make these investments to think about long-term issues. That led to discussion of how do you manage things like environment and government risk. And now ESG is an emerging topic of discussion here in Russia,” says Remy Briand, head of ESG at Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI) during an ESG panel at the St Petersburg International Economic Forum (SPIEF) in the middle of June.

There are still no formal ESG requirements when making investment decisions but funds are starting to adopt them voluntarily as they realise these changes are coming and there is no escaping them. Today ESG factors are already affecting the capital markets and investment decisions. Banks and funds are already selling, or avoiding, stocks if they score poorly in the ESG rankings. Companies in Russia are waking up to the need to improve their ESG record and some of them have already lost substantial shareholders as a result of under par ESG scores, market participants tell bne IntelliNews.

“The trends are entering our life very quickly. We are not talking just about new investors but there is a risk of losing existing investors as well. Companies really need to pay attention to it. If we don't have these credentials then it is nearly impossible to involve European and US investors. We have seen it as necessary to pay attention to these issues over the last three years,” says Pavel Grachev, chief executive officer of Polyus Gold.

Commitment to the cost of clean-up

Several of Russia’s companies have now embraced the new ideas, despite the extra costs they incur, with open arms. Polyus Gold was recently included in the MSCI ranking of ESG leaders.

“There are only six companies in this index. We are third after Novatek and Lukoil. This is a ranking for companies for sustainable development. This is not just about formal criteria to be included in the ESG ranking, but just as important is the motivation to be included,” Polyus’ Grachev says.

Russia’s giant metal producer Norilsk Nickel is another one that has decided to change its spots. The nickel, copper and PGM (platinum group metals) plant is based in the far north of Russia at the site of a former Gulag camp.

“Norilsk used to be for decades the largest polluter in the world, or at least the northern hemisphere. That was due to the decisions that were implemented in the 30s through to the 60s when the prevailing environment was the neglect of the environment and other aspects of what we now call the ESG concept,” says Andrey Bugrov, senior vice president, deputy chairman of the board of directors, MMC Norilsk Nickel.

The company has embarked on a five-year programme to clean up its act — literally. It has introduced new technology to remove sulphur from its emission gases and by 2023 it should be removing 75% of those emissions.

“But ESG is costly,” says Bugrov. “The sulphur capture project will cost $2.5bn and it doesn't increase my production. It just goes into my bottom line. It is important to delineate the two sides of metals and mining: the one that pollutes the atmosphere, but there is the upside too including the catalytic converters as without them the populations of big cites would suffocate.”

G

Of the three criteria the G, or governance, part is probably the most familiar to investors. In Russia the drive to improve corporate governance was kicked off by oil major Yukos in about 2000 when it went from being the bad boy of corporate governance to a leading light. As the boom years started Yukos began quarterly GAPP financial reporting and introduced new transparent policies in its relations with investors. The stock rocketed, rising from around $0.20 in 1999 to a peak of $15 over three years.

“G is the most important for investors. Russia is famous for its governance. The boom in the noughties was linked to the oligarch companies which were the main driver,” says Alexei Yakovitsky, global chief executive officer at VTB Capital. “The big owners of Russian companies have a very positive experience as they found that if you follow the rules set by western investors then you can be very successful.”

Russia’s leading exchange Moscow Exchange (MOEX) has kept the ball rolling by insisting companies that want to list meet strict compliance criteria.

“We want to create a quality market for investors that are including strict criteria in the listing requirements. MOEX is the driving engine of these changes. MOEX pays attention to the G — to corporate governance and general governance. We reformed our listing requirement in 2014 to improve governance and now it is one of the strictest in the world. First is the need for an independent board of directors and steering committee,” says Anna Vasilenko, managing director for key clients and issuer relations at MOEX.

E

Defining the contribution or harm a company does to the environment is a more complicated concept. It is easy to say that a big metals or petrochemical plant is a polluter, because they are, but the equation doesn't end there. Norilsk was one of the biggest polluters in the whole world, but the PGMs it produces are used in cars and massively reduce CO2 emissions.

“As we produce nickel and PGMs one has to recognise we are contributing to the green economy as they are used in catalytic converters. Every third or fourth car in the US market uses our metals in these converters,” says Norilsk’s Bugrov.

Sibur has a similar issue. The giant petrochemical company doesn't produce any oil and gas itself, but buys by-products from the majors and processes it to make its range of polymers, as Dmitry Konov, chairman of the management board of Sibur Holding, described to bne IntelliNews in detail in the feature “Plastics in the snow” in December 2018.

“We used the associated gas as raw material that would otherwise would be flared off. So this is a positive contribution to the environment but it is not taken into account in any of the rankings,” says Konov.

Sibur is a global company and the petrochemicals it produces have a far-reaching impact on the environment beyond the mere making of its polymers.

“What we produce — synthetic materials — release less CO2 and we can help other companies use less materials in their own businesses, which also has a positive effect,” says Konov.

Konov adds that government plays a role here too as while plastics are processable and can be used as stock to make other materials, the bigger issue is to collect plastics that have been used and currently end up in landfills — currently a hot domestic political issue as Russians have been protesting against landfills. However, the government has responded and in Moscow at least the city is introducing laws to force Russians to start sorting their trash for the first time.

“We are still in ESG 1.0 — the simple view of these issues. In ESG 2.0 it will be more nuanced and ESG 3.0 you will be able to bring all the factors together to have a complete view of what you want to do as an asset manager. Like in Norilsk’s case it is important to look at the external realities,” says Jean Raby, chief executive officer of Natixis Investment Managers, which has been following a sustainable investment strategy for years.

It’s easy to get stuck looking at a tree and losing sight of the forest. Investors have been drawn to the Tesla electric car, for example, as it seems to be a technology of the future, whereas they dumped VW stocks after the company got caught cheating on its emissions levels.

“You might want to invest in Tesla because their cars are cleaner, instead of VW. But Tesla will produce 200,000 cars in total this year whereas VW will produce millions. So if VW make any improvements it is VW that will have the real impact on the environment,” says Raby.

S

For many large Russian companies the S part is hardwired into their genes thanks to the Soviet legacy and Russia’s harsh weather. The big raw material producers tend to be located in the tundra in the middle of nowhere and entire cities were built to house the workforce sent there to exploit the rich deposits. That means the HR departments are intimately intertwined with the local city and its life.

“We spent RUB8bn last year on the social aspects of our faculties and their surroundings. Some 17,500 people work for us and all our cities are mono-cities. We are happy we can take an active part in these communities. We build stadia and ski resorts. We give RUB1.5bn to charity and have a children’s initiative for their spiritual development. There are classes at local schools where they intensively study maths and chemistry. And we have supported 20 universities with placements where students will come and work for us after they finish,” says Evgeniy Novitskiy, first deputy general director of the PhosAgro fertiliser producer.

Exclusion to inclusion

Raby goes on to point out that until recently it was seen a breach of their fiduciary duty for asset managers to consider non-financial criteria like ESG when assessing an investment decision. The change to start taking ESG criteria into account is a fairly recent development.

“Making investment decisions that take the environmental impact into account so far has been an exclusion approach. We don't invest in fossil fuels. We don't invest in extractive industries. And there has been a big debate about nuclear power,” says Raby. “The social part has been a box-ticking exercise. Do they have a worker safety policy? Do they have women on the board?”

That will have to change now, as companies need to embrace the whole concept of ESG and build it into the heart of their businesses.

“These days ESG has gone from a nice-to-have to a must-have thing. If you don't want to lose existing investors and want to attract new ones then this is already a must,” says Oleg Goshchansky, chairman and managing partner of KPMG in Russia and the CIS

And ESG could turn out to be a boon for Russian companies as it is one of the few ways they have to undo the “Russian discount” on their market capitalisation valuations.

All emerging markets stocks are marked down for their emerging market risk. But in Russia’s case it has a discount on top of the discount for its specific “Russia risk” that cuts the valuation of Russian assets in half from their already depressed emerging market status level.

“Russian IT companies are the easiest to sell to international investors as the Russian discount plays the least role in this sector. But for more traditional companies ESG is one of the unique ways to minimise this Russian discount — especially if investors are specifically looking for ESG compliant companies,” says Dmitriy Sedov, chairman, Goldman Sachs Russia.

It is in everyone’s interests to pursue better ESG strategies, as some companies in Russia have already reported that they have lost investors in just the last year as the self-adopted conditionality is phased in, thanks to their inadequate ESG scores. The issue of improving their stories is already on the agenda of management boards in many of Russia’s biggest companies.

“It is difficult to evaluate the Russian discount. But there is also the G factor that is becoming more and more important. It is a real issue for managers, and it is a KPI [key performance indicator]. It is regularly on the agenda for Russian boards,” says Alexander Shevelyov, chief executive officer of Russian steel giant Severstal Management.

This article is the cover story in this month's flagship

This article is the cover story in this month's flagship Features

US expands oil sanctions on Russia

US President Donald Trump imposed his first sanctions on Russia’s two largest oil companies on October 22, the state-owned Rosneft and the privately-owned Lukoil in the latest flip flop by the US president.

Draghi urges ‘pragmatic federalism’ as EU faces defeat in Ukraine and economic crises

The European Union must embrace “pragmatic federalism” to respond to mounting global and internal challenges, said former Italian prime minister Mario Draghi of Europe’s failure to face an accelerating slide into irrelevance.

US denies negotiating with China over Taiwan, as Beijing presses for reunification

Marco Rubio, the US Secretary of State, told reporters that the administration of Donald Trump is not contemplating any agreement that would compromise Taiwan’s status.

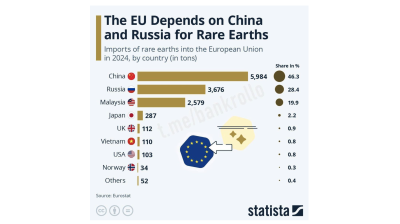

Asian economies weigh their options amid fears of over-reliance on Chinese rare-earths

Just how control over these critical minerals plays out will be a long fought battle lasting decades, and one that will increasingly define Asia’s industrial future.