The first ever joint public event by the heads of the CIA and Britain's SIS – better known as MI6 – saw them address a wide range of topics, from Iran and AI to, predictably enough, Russia. MI6’s Sir Richard Moore ruefully observed that “Russian intelligence services have gone a bit feral,” as they step up a campaign of sabotage and subversion that the CIA's Bill Burns called “reckless and dangerous.”

It is certainly impossible to deny that this has been an escalating campaign. In the States, the Department of Justice has charged five Russian military intelligence (GU) officers with taking part in cyber operations, and also unveiled what is claimed to be a massive attempt to meddle in the forthcoming elections in support of Donald Trump. In Europe, though, matters have taken a much more kinetic turn, with the assassination of a defector in Spain, arson attacks from Britain to Poland, and a range of other, often low-level, disruptive acts of violence, intimidation and disruption, including an alleged plot to murder Armin Papperger, outspoken CEO of the Rheinmetall arms firm.

To a considerable degree, this seems to reflect a calculation that, unable plausibly to threaten Europe with military force – except with mutually destructive nuclear weapons – Moscow's best chance of trying to get aid to Ukraine scaled back or suspended is through this campaign of active measures. By trying to stir up divisive politics and also demonstrate that there is a direct impact on the stability of security of the continent, the thinking is that this will make cooperation harder and generate a public backlash against backing Kyiv.

It is, to be blunt, a deeply questionable strategy. It seems very unlikely that Moscow can create sufficiently serious a range of impacts meaningfully to affect public opinion. Furthermore, (much like sanctions on Russia) such campaigns more often harden that opinion rather than undermine it. So far, the hawks in Europe have had trouble pushing their notions that Russia poses a direct and existential threat to the West, and that 'victory' in Ukraine – whatever that means in practice – is the only way to forestall World War III. Moscow's own hawks could well prove their best allies.

However, it is also likely that there is another reason behind this campaign, which seems to have been initiated or sanctioned by the Kremlin last year, one rooted in a fundamental misunderstanding of the dynamic between Kyiv and its Western allies. Vladimir Putin himself appears genuinely to believe his rhetoric to the effect that the war in Ukraine is merely the most obvious and pyrotechnic theatre in a wider conflict with the West, and further that Kyiv is simply its pawn. Of course, there is an obvious contradiction with the evident tensions visible as Ukraine begs and browbeats its allies for more support and fewer restraints, but none of this seems to shake a simplistic belief on the part of Putin and many of his closest cronies and advisers (not least, his erstwhile Security Council secretary, Nikolai Patrushev) that Kyiv ultimately does what Washington (and even London) decrees.

This puts a different complexion on the covert campaign Ukraine's Security Service (SBU) and military intelligence (HUR) have been waging inside Russia. Through its own agents, willing sympathisers, dupes and blackmailed proxies, Kyiv has been bringing the war to Russia to rather more successful degree. There have been assassinations, such as of vociferous pro-war propagandist Vladlen Tatarsky, Daria Dugina, daughter of nationalist philosopher Alexander, and Stanislav Rzhitsky, a submarine commander whose vessel launched missiles at Ukrainian cities. There have been arson attacks on military commissariats and other government offices, even train derailments.

To Putin, the sabotage campaign in Europe is presumably also both punishment and deterrence: you encouraged or instructed the Ukrainians to wage a terrorist campaign in Russia; now see how you like it.

Of course, in this – as in so much – he is wrong, but it illustrates a fundamental challenge for the West in trying, through rhetoric, signalling, diplomacy and, ultimately, action, to influence Russian behaviour. It certainly does not mean that we ought to let our own policy be shaped by Putin's prejudices and fantasies. What it does mean, though, is that we ought to be paying more attention to what he says as a guide to what we may face next. Of course, he lies, he knowingly misrepresents, he wilfully trolls – as he did when, at the Vladivostok economic forum, he suggested he hoped Kamala Harris would beat Donald Trump in the presidential race. However, it is all too easy to discount many of his more outlandish assertions as red meat for the nationalists or misdirection. The sad truth is that he believes much of the nonsense he speaks.

The significance for Western policy is thus two-fold. On the one hand, we should listen to Putin more carefully. The French diplomat who airily assured me that he didn't bother reading the digests of Putin's speeches because “anything important in them we already know, and all the rest we don't need to know” sadly spoke for too many such figures in the West. The other is that we should attempt the unenviable task of putting ourselves in his brain so as to try to predict how he will view developments and what he will do as a result. On the kinetic battlefield, the Ukrainians have shown with their Kursk offensive that they can seize the initiative. More widely, though, it is hard to avoid a suspicion that the West is fundamentally reactive, funnelling money and materiel to Ukraine while hoping Putin gives up. Had we been more imaginative in thinking through how Moscow would react to our support for Ukraine, and how it would compensate for the expulsion of its agents, perhaps we would have been better placed to prevent rather than react to Putin's campaign of sabotage, subversion and assassination.

Opinion

COMMENT: Hungary’s investment slump shows signs of bottoming, but EU tensions still cast a long shadow

Hungary’s economy has fallen behind its Central European peers in recent years, and the root of this underperformance lies in a sharp and protracted collapse in investment. But a possible change of government next year could change things.

IMF: Global economic outlook shows modest change amid policy shifts and complex forces

Dialing down uncertainty, reducing vulnerabilities, and investing in innovation can help deliver durable economic gains.

COMMENT: China’s new export controls are narrower than first appears

A closer inspection suggests that the scope of China’s new controls on rare earths is narrower than many had initially feared. But they still give officials plenty of leverage over global supply chains, according to Capital Economics.

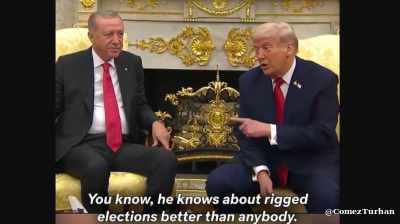

BEYOND THE BOSPORUS: Consumed by the Donald Trump Gaza Show? You’d do well to remember the Erdogan Episode

Nature of Turkey-US relations has become transparent under an American president who doesn’t deign to care what people think.