The total war loss to Ukraine's economy is up to $600bn, according to an update to previous estimates issued by the Kyiv School of Economics on April 12.

The direct losses of Ukraine's economy due to the destruction of and damage to civilian and military infrastructure, documented in public sources, have increased by $12.2bn from the previous estimate issued at the end of March of $565bn, according to the new study: “Russia will pay”.

According to the study, as of April 11, the total amount of direct documented infrastructure losses, based on public sources alone, has reached UAH2.4 trillion ($80.4bn).

According to joint estimates of the Ministry of Economy and the KSE, the total losses of Ukraine's economy due to the war, including both direct and indirect losses, including GDP decline, investment cessation, labour outflows, additional defence and social support costs, range from $564bn to $600bn.

Some 7mn people have been displaced and around 4.5mn have left the country. Russian artillery and bombs have flattened entire cities in the south of Ukraine, while missiles have targeted roads, rail and other infrastructure across the country.

The estimates for the cost of the war vary and are rising daily as the war continues. Researchers from the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) put the total cost of rebuilding Ukraine in the region of $220bn-$540bn, or between one and two and half times the value of GDP just before the war started.

The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw) reckons that the affected regions together make up about 29% of Ukrainian GDP. Electricity consumption, a proxy for activity, is down by around a third compared with a year ago, according to wiiw.

But a National Bank of Ukraine (NBU) survey also found that 30% of Ukraine’s firms have stopped producing entirely, another 45% have reduced their output and electricity consumption is down by 35%.

The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) puts the hit to production even higher: as of the middle of April the fighting is happening on territories that produce around 60% of Ukrainian GDP, the development bank said in a recent report.

The World Bank reckons that GDP will contract by 45% this year as economists scramble to keep up with the scale of the expanding fighting. The World Bank believes that Ukraine’s economy, even with concerted reconstruction efforts, will only recover to a third of its pre-war GDP by 2025. Ukraine’s GDP could collapse to one third of what it was pre-war, International Monetary Fund (IMF) managing director Kristalina Georgieva said on March 22. The EBRD revised its growth forecast for Ukraine in 2022 to -1.7% on March 31, which will almost certainly be significantly revised downwards soon.

The government is pouring money into the war, much of it being provided by Western partners. Ukraine will see an increase in the state budget deficit of Ukraine from $2.7bn in March to $5-7bn in April and May per month, Finance Minister Serhiy Marchenko predicted on April 12, according to reports.

Marchenko estimates that infrastructure losses have skyrocketed to $270bn, up from the $120bn in damage Ukraine’s prime minister cited at the end of March. Over 7,000 residential buildings have been destroyed or damaged in the war. The recently established Kyiv School of Economics puts the value of destroyed housing at $29bn.

Grain exports decreased by almost 90%, total exports fell by half. The final fall in GDP will depend on the duration of hostilities, the minister said.

The state budget deficit in 2022 was originally projected at 3.5% of GDP, but Marchenko noted that it would grow many times over, depending on the duration of the war.

Ukraine’s access to the international capital has been cut off by the war and the domestic bond market, a major source of funding of the state, has also been closed. With the finance ministry losing tax revenues of about $2bn a month, it has started to issue emergency military bonds to investors and raised UAH6bn ($203mn) during the seventh auction on April 12. Investors were presented with two issues of hryvnia military bonds with a maturity of 6 months and 1.3 years at rates of 10% and 11% respectively. Each of the seven auctions so far have raised roughly similar amounts; however, the approximately $1.4bn raised is insufficient to fund the current spending.

Ukraine’s financing now depends almost entirely on grants and loans from its Western partners, which have promised some $25bn in total, of which $7bn has already been received as of mid-April.

Keeping agriculture on track has been a key goal, as grain exports are one of Ukraine’s foreign exchange earners. Farmers have been granted UAH20bn ($675mn) of loans as the planting season is about to begin and manufacturers are getting help to relocate within Ukraine.

The Russian naval blockade has closed down shipping completely, the main export channel. While grain can be shipped by train to Europe, heavy products like coal and metals rely on ships. Moreover, the change of gauge at the EU border hampers railway exports as well. The government says that 80% of exports can still leave the country by rail, but other commentators are a lot more pessimistic.

De-mining the country post-war is also going to be a heavy burden. Before this war Ukraine’s defence ministry put the cost of demining the Donbas region, which was invaded by Russia in 2014, at €650mn, reports The Economist. In Iraq demining cost roughly $1bn and took a decade to complete.

Rebuilding damaged infrastructure and industrial facilities – power plants and factories to bridges and roads – will cost at least $50bn, according to the Kyiv School.

While experts have variously put the cost of the physical damage at between $100bn and $220bn in total, the government has estimated the total loss to the economy, including lost revenues and missing investment, is a far larger $565bn, Deputy Minister of Economics Yulia Svyridenko announced at the end of March.

At the end of March the KSE estimated the cost of the war is $565bn, including:

$119bn loss of infrastructure (almost 8,000 km of roads destroyed and damaged, dozens of railway stations, airports);

$112bn decline in 2022 GDP;

$90.5bn in civilian property losses (10mn square metres of housing, 200,000 cars, 5mn people suffering food insecurity);

$80bn in loss of enterprises and organisations;

$54bn in losses from direct investment in the Ukrainian economy; and

$48bn in losses to the state budget.

Lost production from shuttered factories and missing investment mean that even the infrastructure that is still standing will need upgrading. Another study by wiiw finds that, after the invasion of Donbas in 2014, depreciation made up 60% of war-related infrastructure losses by the end of 2019, The Economist reports. The prime minister’s estimate of a cost of $119bn to infrastructure and industry this time may therefore not be far off.

Ukraine’s government has already set up a recovery fund, mirrored by a similar fund set up by the IMF. Funding will have to come from Western governments, international organisations and private investors. Tim Ash, senior sovereign strategist at BlueBay Asset Management, has suggested that US and EU powers use their special drawing rights (SDR) allocations that were issued to all countries by the IMF last year as part of the response to the coronacrisis. These total some $290bn and are currently sitting idle on the IMF balance sheet.

“This money could be released tomorrow. There is no technical problem preventing it. It is simply a question of political will,” Ash said in an email to clients.

Others have suggested that the sanctions on the Central Bank of Russia’s gross international reserves (GIR) on February 27 that froze some $300bn could be used for repairs and/or reparations. However, this idea has not been seriously discussed yet but may be part of a peace deal. Another option is that it is possible Ukraine could be fast-tracked for EU membership, when it would become eligible for EU infrastructure grants. Poland, which is about the same size as Ukraine, has received a total of €106bn in investment funds between 2014 and 2020. In the 15 years after it joined the EU, its GDP per person increased by more than 80%, The Economist reports. EU President Ursula von der Leyen gave a speech during a visit to Kyiv in April where she said that Ukraine “belonged in the European family."

"We hope that [Ukraine] will get the status of a candidate for membership at the summit of leaders of the European Union in June this year, and this process will open new political horizons for us, primarily financial horizons," Deputy Prime Minister for European and Euro-Atlantic Integration of Ukraine Olha Stefanishyna said during the nationwide telethon, Ukrinform reported on 11 April.

The international financial institutions (IFIs) like the EBRD could also be a major source of funding. Ukraine became the EBRD’s biggest client country after the latter withdrew from Russia in 2014, and has since then invested a total of €18bn in total into Ukraine.

News

US strikes on drug vessels kill 14 in deadliest day of Trump's narcotics campaign

The US military killed 14 people in strikes on four vessels allegedly transporting narcotics in the eastern Pacific Ocean, marking the deadliest single day since President Donald Trump began his controversial campaign against drug trafficking.

Russia withdraws from Cold War plutonium disposal pact with US

Russian President Vladimir Putin has formally withdrawn from a key arms control agreement with the United States governing the disposal of weapons-grade plutonium, as the few remaining nuclear security accords between the two powers vanish.

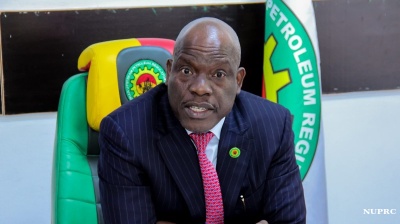

Nigeria’s NUPRC holds exploratory talks with Bank of America on upstream financing

Nigeria's upstream regulator, NUPRC, has held exploratory talks with Bank of America as the country looks to attract new capital and revive crude output, after falling short of its OPEC+ quota.

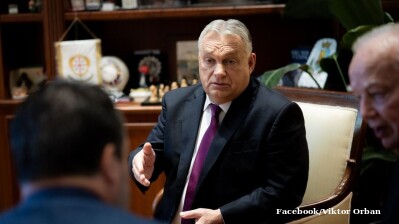

European diplomacy should have stopped war, Orban tells Italian broadcaster

The job of European diplomacy would have been stopping the war in Ukraine, but Brussels has become "irrelevant" by deciding not to negotiate, Prime Minister Viktor Orban told an Italian TV channel on October 28.