When it dawned on the world that Donald Trump had actually completed his stunning comeback to the top of world politics, Polish President Andrzej Duda took to social media.

“Congratulations, Mr President! You made it happen,” the Polish president posted on X.

Just over 90 minutes later, Prime Minister Donald Tusk logged on. “Congratulations to Donald Trump on winning the election. I look forward to our cooperation for the good of the American and Polish nations,” Tusk posted.

Unlike the opposition Law and Justice's (PiS's) supporting president, who knows – and apparently likes – Trump from his first term in the Oval Office, Tusk and his camp have made it clear Kamala Harris would have been their preferred US president.

Tusk will now hope Duda will work hand in hand with the government to make Trump get over his criticism of Nato and shelve his plan to “end war in Ukraine in 24 hours”, which Poland fears means conceding to Putin. But it will mostly fall on Tusk to handle Trump’s famed – and feared – erratic and capricious behaviour, such as his accusations that Europe is “freeloading” on the US for defence.

Tale of two Donalds

With Trump in charge, Tusk has just been presented with an extra level of difficulty in how he and Poland’s Foreign Minister Radoslaw Sikorski (whose wife, columnist Anne Applebaum likened Trump to Hitler, Stalin, and Mussolini) are going to lead their country’s foreign policy in the coming years.

Warsaw is worried that Trump is capable of making abrupt decisions that would end the West’s involvement in Ukraine, forcing Kyiv to concede occupied territories to Russia and effectively giving the Kremlin time to regroup before attacking Ukraine again. Poland is concerned it might become Moscow’s next target if the Kremlin brings Ukraine to heel.

Yet Tusk had handled Trump before as the European Council President between 2015 and 2019 and believes he has the measure of him. “I know Trump well from those times. He is a demanding partner but we had a good relationship,” Tusk told journalists on November 7.

“One of Trump’s principles is being unpredictable, which he uses purportedly to surprise his enemies – but also his allies. Does that mean Washington is about to U-turn on Ukraine? I honestly don’t think there is anyone in the world today who is able to answer that question,” Tusk said.

“It’s not Poland that will decide who President Trump will do about Ukraine and Russia but it’s the job of the Polish government to define Polish interests well and ensure safeguarding them,” Tusk also said.

King of Europe again?

In the campaign ahead of last year’s election that elevated him to power, Tusk said repeatedly that his experience on the international stage as the European Council President will pay off by returning Poland to the top tier of EU’s decision makers. But since taking office in December, the Polish PM’s foreign policy record is a mixed bag.

Arguably, Tusk’s biggest success arrived in May, when the European Union lifted the Article 7 procedure against Poland – a kind of retribution slapped on Warsaw under the previous government of Law and Justice’s (PiS’s) for reforms that, Brussels said, damaged the rule of law.

Brussels soon followed with unblocking billions of euros from the bloc’s cohesion and pandemic recovery funds. Both came in return for the mere prospect of undoing the previous government’s war on the rule of law.

Meanwhile, the Tusk government has since managed little in the way of actually restoring the rule of law, critics have said. The PM says his hands are tied as long as Duda remains president. Tusk does not have enough votes in the parliament to override Duda's vetoes.

Tusk also made his mark on the EU by announcing Poland was considering suspending the right to asylum to counter “hybrid war” waged by Belarus – and by extension, Russia – on the Polish border.

Following an outcry by human rights defenders in Poland, an unfazed Tusk took his message to Brussels and won the backing of EU leaders who – he said – regarded Poland’s position on the way Belarus had instrumentalised migration as “100%" in the bloc’s political mainstream.

Poland's improved clout in the EU is also underscored by the nomination of Polish candidate Piotr Serafin as the new European Commissioner for Budget. This high-profile role comes at a critical time with negotiations over the next EU budget framework fast approaching.

PiS wasn't wrong, after all

That said, the Tusk government’s foreign policy – at least in the EU context – is in many aspects similar to predecessors from PiS, who Tusk invariably painted as “anti-European”.

The PM – who PiS ritually accuses of being a “German protege” – remains frustrated by Berlin’s inability to act more decisively on matters of European security and has criticised the now-defunct Olaf Scholz’s Ampel Coalition for that.

Other than his stance on migration, Tusk also spoke against the fundamental reform of EU’s environmental policy by voting against the Nature Restoration Law, a comprehensive package of measures to protect biodiversity.

Tusk also continued PiS’s tough approach to imports of Ukrainian agricultural produce, which are allegedly ruining Polish farmers. Warsaw even went so far as far as threatening it would block Ukraine’s entry to the EU if Kyiv does not move the needle on the long-standing historical issue of wartime massacres of Poles by Ukrainian nationalist guerrillas in the 1940s.

Tusk has suffered defeats on the international stage, too. The biggest one came in October, when Western leaders meeting in Berlin – US President Joe Biden, Chancellor Scholz, French President Emmanuel Macron, and UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer – did not think it necessary to invite Tusk.

“Poland should have been included, given that it is one of the countries most actively engaged in supporting Ukraine on multiple fronts. Additionally, the vast majority—around 90% —of aid to Ukraine passes through Poland,” the foreign ministry said at the time.

Stormy waters of foreign policy

The next – and arguably the most serious test to date – of Tusk as a foreign policy leader is coming soon. Poland is taking over the EU’s rotating presidency on January 1, just weeks before Trump’s inauguration as the 47th president of the US.

That will put Tusk in the eye of the storm as he will play an important role in handling the first possible shock wave of the Trump’s presidency, especially with regard to Europe’s security but also Trump’s plans to disrupt world trade and undermine global climate policy. On the EU front, backstage talks will continue on the bloc’s next long-term budget, which the European Commission will table sometime in 2025, to be agreed by 2028.

Domestically, how Tusk will handle foreign policy could decide the fate of his coalition government. As security rises to the top of international agenda, it will also feature high in next year’s presidential election in Poland.

While Tusk will not run, his candidate will be seen through the government’s success – or lack of it – in foreign policy. That could ultimately weigh in on who replaces Duda in mid-2025, with with another PiS president all but certain to block any major reforms, potentially leading to a premature end of the Tusk government and a snap election.

Features

US expands oil sanctions on Russia

US President Donald Trump imposed his first sanctions on Russia’s two largest oil companies on October 22, the state-owned Rosneft and the privately-owned Lukoil in the latest flip flop by the US president.

Draghi urges ‘pragmatic federalism’ as EU faces defeat in Ukraine and economic crises

The European Union must embrace “pragmatic federalism” to respond to mounting global and internal challenges, said former Italian prime minister Mario Draghi of Europe’s failure to face an accelerating slide into irrelevance.

US denies negotiating with China over Taiwan, as Beijing presses for reunification

Marco Rubio, the US Secretary of State, told reporters that the administration of Donald Trump is not contemplating any agreement that would compromise Taiwan’s status.

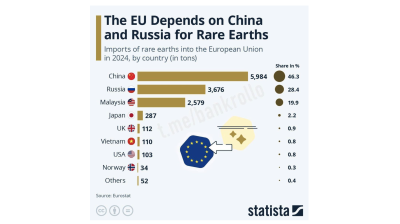

Asian economies weigh their options amid fears of over-reliance on Chinese rare-earths

Just how control over these critical minerals plays out will be a long fought battle lasting decades, and one that will increasingly define Asia’s industrial future.