Turkey’s President, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, appears to have secured his own re-election.

He now has to find a way to avoid what appears to be an imminent financial crisis.

Turkey, of course, has enormous geopolitical importance, and President Erdogan is a master at using Turkey’s strategic position to generate emergency financing.

But Turkey’s finances were pushed to the breaking point by his efforts to juice the economy—and avoid a large fall in Turkey’s currency—prior to the election. The post-election pivot toward orthodoxy can regenerate the reserves that were spent over the last three months.

Turkey is on the edge of truly running out of usable foreign exchange reserves—and facing a choice between selling its gold, an avoidable default, or swallowing the bitter pill of a complete policy reversal and possibly an IMF program.

Turkey’s financial difficulties are all the more interesting because Turkey doesn’t have a classic fiscal problem.

That actually doesn’t surprise me. The world learned in the 1990s that not all payments crises originate from excessive direct spending by the government. However, Turkey does face the risk of a classic balance of payments crisis. Its economy is running too hot relative to Turkey’s ability to borrow externally, and Turkey can no longer bridge the gap between its imports and exports by running down its reserves.

Turkey also has an interesting balance sheet problem—to revive a useful if now somewhat old-fashioned framework for thinking about risks that aren’t mostly fiscal.

Turkey’s government doesn’t have a tonne of formal public debt.

But Turkey’s central bank has borrowed a tonne of foreign exchange from Turkey’s own banks and from other governments. It then spent its borrowed foreign exchange defending the lira. The result in some ways could be worse than a standard fiscal crisis. Turkey’s banks have lent so much to Turkey’s central bank (and on a smaller scale, directly to the government) that they cannot honour their domestic dollar deposits, should Turks ever ask for the funds back.

Turkey’s public finances aren’t as good as they seem, as the banks have relied on exchange rate protected lira deposits to finance a large part of their pre-election lending boom—and the government is ultimately on the hook for the cost of this $125 billon deposit protection scheme.

Turkey’s risk of a financial crisis starts with its need for external financing.

Booming credit has pushed up imports, and overwhelmed Turkey’s relatively solid export performance. The current account deficit had fallen to well under $20bn in 2021, but it is on track to reach close to $60bn in 2023.

There is no sign in the trade data that the deficit will close on its own: import growth is still outpacing export growth. Turkey is a perfect example of how a relatively stable exchange rate and high domestic inflation tends to erode a country’s competitiveness.

An external deficit by definition requires the ability to borrow from abroad—or a willingness to sell off your existing assets to cover the deficit.

That is Turkey’s second problem: it isn’t able to consistently attract external finance.

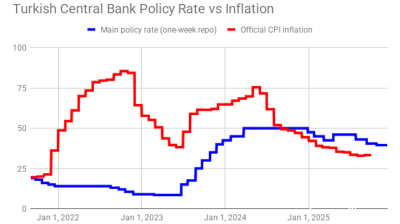

President Erdogan (famously) believes that high interest rates cause inflation, and he has personally forced Turkey’s central bank to cut interest rates even while inflation remains quite high. Turkey’s policy rate is 8.5%—and reported headline inflation is over 40% (and some informal measures suggest it is actually higher).

Foreign investors simply don’t want to hold lira assets when lira interest rates are being held artificially low and there is a clear risk of lira depreciation.

Until recently, Turkey could borrow in the foreign currency bond market, but not on the scale needed to fully cover such a large external deficit—even with indirect support from some of the GCC countries for its bond offerings.

The result is a classic problem that a number of weak emerging markets have faced recently: an external deficit that exceeds available market financing.

That leads directly to Turkey’s second problem: it is running out of reserves.

The 2023 external deficit, unlike the 2022 deficit, has been financed largely by selling down Turkey’s reserves.

The scale of the sales actually is bigger than meets the eye, as the Saudis (through the Saudi Fund for Development) put $5bn on deposit at Turkey’s central bank in March. All else equal, reserves should have increased by the same amount. The fact that reserves fell by $0.5bn in March in the balance of payments data is thus telling. The balance of payments data shows a $14bn fall in the first three months of the year even with $6bn of inflows from net deposits. The Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey’s (CBRT's) reported reserves suggest a similar $20bn fall in net reserves in April and May (weekly numbers are here and here). All told, reserves are down close to $30bn on the year, even with over $10bn in external borrowing by the central bank.

Turkey now reports holding just under $50bn in foreign exchange reserves, and another $50bn in gold. But not all of Turkey's $48bn in foreign exchange is really usable—close to $19bn comes from swap arrangements with Qatar and the Emirates. Turkey thus has a lot of its reserves in Qatari riyal and Emirati dirham. Both are pegged to the dollar, and Turkey could ask for dollars against its “soft” currency reserves, but realistically it could only get dollars with the consent of Qatari and Emirati central banks. Turkey’s actual hard currency reserves are thus currently closer to $30bn.

That isn't a lot of reserves for an economy with a $60bn current account deficit that has been selling well over $5bn a month into the market to keep the currency stable earlier in the year (and much more in the month of May).

Depending on the pace of reserve sales in the next few weeks—and the size of and composition of the latest slug of financing from the GCC countries—and Turkey could be out of usable reserves sometime this summer.

To be sure, Erdogan no doubt intends to do another round of deals with Turkey’s neighbours to close Turkey’s financing gap.

Erdogan has been able to get funds from almost everyone. Even countries that don’t like each other have given money to Erdogan to try to make sure Turkey’s doesn’t swing toward their rivals. The Qataris and the Saudis, for example, don’t have the closest relationship. But both have provided Erdogan with funding—the Qataris to cement an alliance with the Islamist Erdogan, and the Saudis and the Emiratis to keep Turkey from migrating fully into Qatar’s camp. Turkey has also gotten a deposit from the Azeris, swap lines from China and Korea, and a bit of funding from Russia’s state atomic energy company.

The last one has to be the deal of the century. Rosatom is building a large nuclear power plant in Turkey. Rosatom isn’t under sanction, as it is too strategic to sanction because it supplies much of the world’s uranium. But in order to assure that Rosatom would be able to finance the construction of this power plant in the event of future sanctions, Turkey convinced Rosatom to put $5bn into a dollar account held by its Turkish subsidiary. Rosatom in turn raised the money from Gazprombank—so Europe’s oil purchases from Russia last summer effectively were channelled through a Russian bank and a Russian SoE to help cover Turkey’s balance of payments deficit (the flows are all visible in the balance of payments, this all checks out).

There are also reports and even bigger rumours that Russia is providing Turkey with gas on credit—and not demanding that Turkey’s big state gas importer (BOTAS) pay to help Erdogan out.

Yet Erdogan also sells drones to Ukraine and is central to Ukraine’s ability to ship its harvest out through the Black Sea.

Given his past success, Erdogan certainly will be tempted to try to gin up yet another round of financing from Turkey’s neighbours and the global East.

But at some point, the financial risks of lending to Erdogan's unorthodox policy mix has to outweigh the geostrategic costs of not financing Erdogan.

Turkey’s central bank, which has received the bulk of Turkey’s geopolitical funding, now has about $50bn in external debt (the last NIIP data point is in March, and the CBRT’s data suggests additional borrowing in the last two months).

The external debt of Turkey’s central bank though is actually far smaller than the internal debt of Turkey’s central bank.

Turkey’s central bank has now raised a tonne of dollars by borrowing from Turkey’s own banks, and thus ultimately the foreign exchange deposits of Turkey’s citizens.

Turkey’s central bank borrows from the banks "on balance sheet"—it has about $90bn in foreign currency deposits from Turkey’s banks (so Turkey’s central bank in theory owes dollars to the banks) and another $10bn in gold deposits.

And Turkey’s central bank borrows from the banks off balance sheet—it has provided about $40bn of lira for another $40bn of dollars with the domestic banks through swap contracts (for more on these swaps, see, among other sources, Charts IV.2.6 and Chart IV.2.11of Turkey's November 2022 Financial Stability Report).

The total amount of foreign currency that the central bank has borrowed domestically is thus about $130bn. The Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey has taken in another $20bn (ballpark) from the world in deposits, and swapped for another $20bn of GCC currencies that are technically counted in its reserves. So total dollar and euro liabilities are around $150bn—way more than the $30bn in liquid foreign currency that the central bank has left.

Now Turkish savers have historically moved out of lira and into domestic dollar deposits when they have lost confidence in the lira—the funds traditionally haven’t flowed out of Turkey.

But the total foreign currency claims on the combined balance sheet of the central bank and the government—the $150bn in liabilities of the central bank, the $70bn in government of Turkey eurobonds, another $30bn or so of domestic foreign currency loans from Turkey’s banks straight to the government—are way larger than Turkey’s liquid foreign exchange reserves.

All this is missed by looking just at reported public debt, which is an important reason why understanding the balance of payments and the actual balance sheets of key parts of Turkey’s economy really is important. The IMF is running a real risk of forgetting many things it once knew if its vulnerability analysis keeps focusing on fiscal variables (I am not a fan of the IMF’s supposedly state of the art market access debt sustainability framework for precisely this reason).

But there is no real doubt that there are two key flows that matter here:

1) The flow of hard currency from Turkey's banks to Turkey's central bank.

2) The flow of hard currency from Turkey’s strategic allies to the central bank and the eurobond market.

The net result is an economy that, despite having a low level of fiscal debt relative to the size of its economy, actually has a lot of foreign currency denominated debt relative to its foreign currency reserves.*

Over the last few years, the foreign currency balance sheet risks have migrated to the public sector—Turkey’s banks used to borrow globally to fund foreign currency lending firms and to generate dollars to swap (also with global investors) to fund their lira lending. They now borrow domestically to lend to the central bank and the government in hard currency …

Not to mention the $100bn in foreign currency protected deposits that funded the recent lending boom in lira lending.

Not all risks are fiscal. At least not directly.

Erdogan levered up a tonne of balance sheets to keep the currency stable while juicing credit and keeping lira interest rates exceptionally low.

That policy mix effectively bought Erdogan an election.

It also leaves Turkey on the precipice of a financial crisis, with no real choice but to turn toward orthodoxy and hope for the best. Turkey's foreign exchange reserves lasted through the election, but they won't last through the summer without a course correction.

Turkey’s low levels of public debt won't make up for Turkey's lack of liquid foreign exchange reserves. But it will help Turkey deal with its foreign currency liquidity problems if Erdogan can ever accept the need to go to the IMF.

Turkey is a rare country that both meets the exceptional access criteria and could have a large need for foreign exchange. If there ultimately is a programme for Turkey, I would also hope that the IMF doesn’t follow its recent trend of low balling the financing need. A big programme for Turkey would be risky. But there also used to be an understanding that lending too little could be as risky as lending too much.

* The IMF noted back in 2021: "Public debt remains contained, at around 40 percent of GDP, as direct fiscal support—including to workers and vulnerable households— has been relatively modest".

This article was originally published by the Follow the Money blog on the Council of Foreign Relations website here. The work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) Licence.

Features

US denies negotiating with China over Taiwan, as Beijing presses for reunification

Marco Rubio, the US Secretary of State, told reporters that the administration of Donald Trump is not contemplating any agreement that would compromise Taiwan’s status.

Asian economies weigh their options amid fears of over-reliance on Chinese rare-earths

Just how control over these critical minerals plays out will be a long fought battle lasting decades, and one that will increasingly define Asia’s industrial future.

BEYOND THE BOSPORUS: Espionage claims thrown at Imamoglu mean relief at dismissal of CHP court case is short-lived

Wife of Erdogan opponent mocks regime, saying it is also alleged that her husband “set Rome on fire”. Demands investigation.

Turkmenistan’s TAPI gas pipeline takes off

Turkmenistan's 1,800km TAPI gas pipeline breaks ground after 30 years with first 14km completed into Afghanistan, aiming to deliver 33bcm annually to Pakistan and India by 2027 despite geopolitical hurdles.