The recovery from the coronacrisis is progressing faster than expected, according to the latest figures from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), but under half of the countries in the region are set to rebound strongly enough to beat their 2019 GDP this year.

The forecasts for the EBRD region as a whole, which encompasses parts of the Southern and Eastern Mediterranean (SEMED) as well as emerging Europe, are for growth of 4.2% this year, following a contraction of 2.3% in 2020, though the economic performance varies widely from country to country. That is an upward revision of 0.6 percentage points (pp) compared to the EBRD’s previous set of forecasts released in September 2020.

Just four countries – Tajikistan, Turkey, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan – achieved positive growth in 2020. Others will rebound in 2021, but there are still a large number of countries from the region that will need until 2022 to return to the level of GDP they had in 2019.

EBRD president Odile Renaud-Basso told a press event ahead of the release of the report that the bank’s forecasts "show that the recession has been a bit more shallow than expected … we now expect the recovery to be stronger than we forecast in October".

According to Renaud-Basso the stronger-then-expected performance is "very closely related to the fiscal stimulus support and monetary support that helped to preserve economic capacity. When the restrictive measures are lifted, the capacity to rebound is quite strong".

However, she stressed that there are marked differences between countries as well as uncertainties over the future course of the pandemic and access to vaccines.

"We see a strong rebound in industrial production, manufacturing and expert activities, partly because of dynamic growth in Europe and the US. It is more uncertain in services and tourism – the more countries are dependent on services and tourism, and the less on manufacturing, the more likely they are to take some time to recover. The recovery is also dependent on the political situation and stability; some countries have vulnerabilities in that respect."

"Although the revised forecasts give reasons to be optimistic, huge uncertainty remains with regard to the path of the COVID-19 Delta variant which poses particularly large risks for countries that have made less progress on vaccinations and for economies highly reliant on international tourism," said EBRD chief economist Beata Javorcik.

"The picture for 2020 is diverse. While several countries in Central Europe and the Baltic states performed well compared with many advanced European economies thanks to a strong rebound in exports of goods, economies heavily reliant on tourism were hard hit. And in countries afflicted by challenging economic circumstances prior to the pandemic, COVID-19 only compounded existing problems."

Compared to the final pre-crisis year of 2019, the region as a whole is expected to see growth of 1.7% in 2021, but this is driven by a relatively small number of countries.

The strongest growth in GDP between 2019 and 2021 is concentrated in Central Asia, which as a whole is expected to grow by 3.7% over the two-year period, and by 4.5% each in 2021 and 2022. Leading the expansion are Tajikistan with growth of 11.3% forecast this year compared to 2019, Turkmenistan (10.8%) and Uzbekistan (7.3%). All three managed to avoid a recession in 2020.

The EBRD report noted that the outlook for Central Asia has been revised upwards, "although the recovery is far from uniform", it added. Notably, the region's largest economy Kazakhstan is set to grow by a modest 3.6% this year, after contracting by 2.6% in 2020. Forecast growth in 2021 and 2022 reflects higher commodity prices, which benefits commodity exporters, as well as recovering remittances.

Similarly, Turkey achieved growth of 1.8% in 2020, despite a combination of political uncertainty and a heavy toll of COVID-19 cases. It’s now forecast to grow by 5.5% and 4.0% over the coming two years. This growth will be "driven by exports, while domestic demand remains constrained by the impact of continuing containment measures and the weaker financial situation of households," the report said.

Serbia is another strong performer that is expected to see its GDP up by 4.9% this year compared to 2019. With a strong stimulus programme, and benefiting from a diversified economy, Serbia managed to keep its dip in 2020 at just 1.0% and is heading for rebounds of 6.0% and 3.5% respectively in 2021 and 2022.

Elsewhere in Southeast Europe, only Romania (1.9%), Albania (1.1%) and Bulgaria (0.2%) are expected to top their 2019 GDP this year, with the rest of the region still on the road to recovery going into 2022.

Several countries in the region are heavily dependent on tourism, which led to some of the deepest recessions across the emerging Europe region last year. Montenegro, the worst-hit economy by the coronacrisis in 2020, will not return to its 2019 GDP in 2022.

The region’s largest economy, Russia, will just manage to bounce back this year, following a 3.0% contraction in 2020. “In Russia output is seen growing by 3.3 % in 2021 and 3% in 2022 as the easing of restrictions on activity underpins a recovery in domestic demand. The boost from higher commodity prices is expected to be partly offset by a more neutral fiscal and monetary policy stance,” according to the EBRD.

However, Russia is the only country across Eastern Europe and the South Caucasus whose economy is expected to exceed its 2019 GDP this year, with the recoveries in the rest of the region continuing into 2022. This is despite higher commodity prices and strong demand for exports.

In Central Europe and the Baltic states, only three countries, Estonia, Lithuania and Poland, are set to fully rebound this year. The region as a whole is expected to grow by 4.8% in 2021 and 4.6% in 2022 following a 3.9% contraction in 2020.

Another issue highlighted by Renaud-Basso is the capacity of countries in the region to continue with fiscal support. "For a number of countries in the region the fiscal margins are not so large. We see that the increase of their debt has been quite significant at 10% or 15% of GDP on average, so in future the fiscal margin of manoeuvre may be limited. In addition, the appetite for financing emerging markets may be lower … so that may weigh on the recoveries."

The report warns: "In many economies, public debt is now at levels last seen during the transition recession of the early 1990s and may rise further. While bankruptcies have so far remained contained owing to extensive policy support, vulnerabilities may surface when government support measures are withdrawn."

Data

Chobani yoghurt king Hamdi Ulukaya becomes richest Turk

Knocks Murat Ulker into second place in Forbes ranking as his company's valuation leaps to $20bn.

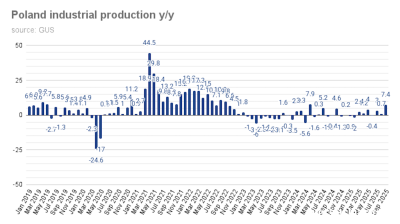

Poland’s industrial production jumps 7.4% y/y in September

September saw an unexpectedly sharp increase in industrial production after the surprise gain of 0.7% y/y in August.

Ukrainian M&A market grows 22% despite war, driven by local investors

Two large acquisitions by agriculture holding MHP and mobile operator Kyivstar accounted for more than half of the total deal value.

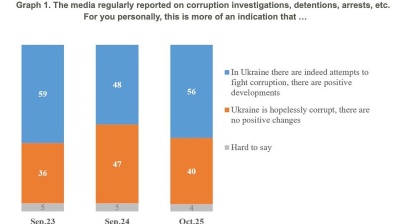

Ukraine’s credibility crisis: corruption perception still haunts economic recovery

Despite an active reform narrative and growing international engagement, corruption remains the biggest drag on Ukraine’s economic credibility, according to a survey by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology.