New research from the University of the Potomac shows that the food favoured in different countries does not necessarily correspond with what is produced locally. A taste for foreign crops was enabled by thirty years of globalisation and increasingly advanced agricultural and transportation technology. Now, this interdependency risks exacerbating food shortages around the world as the war in Ukraine imperils food security.

Wheat is one of the most striking examples. Wheat originated in Central and West Asia and the Mediterranean. Now it is consumed worldwide, and ranks as the most produced agricultural commodity for 14 countries. Wheat is a particularly significant crop right now, because the war in Ukraine is disrupting outflows of wheat from two of the world’s biggest exporters – Ukraine and Russia.

The root of the problem

Russia is the world’s third-biggest wheat producer. Russia and Ukraine together comprise one of the world’s crucial breadbasket regions, accounting for around 30% of the global wheat trade.

A Russian blockade of the Black Sea is preventing some Ukrainian wheat from reaching the market, and satellite photos appear to show Russian ships stealing Ukrainian grain. The effects are already being felt. Wheat prices jumped by 20% in March alone, and are now up 53% since the start of the year.

Wheat is an essential raw material for the processed food industry, so the increase in wheat prices is likely to have a knock-on effect on the prices of other foods, too.

Africa is particularly dependent on Ukraine and Russia for its wheat supplies. About 42% of the continent’s wheat imports came from Ukraine and Russia between 2018-20, according to The Conversation. Wheat prices in Africa are already up 60% since the start of the war. The poorest areas will be hardest hit by the rising prices.

The scale of the looming crisis is enormous. Around 25m tonnes of corn and wheat is currently in storage in Ukraine. That’s the equivalent of the annual consumption of all of the world’s least developed economies.

The crisis isn’t limited to wheat either. A programme of modernisation of Russian agriculture over the past two decades has made it a significant producer – feeding 2bn people worldwide. Russia is the world’s biggest producer of barley and sugar beet, producing almost 15% of the global supply of both crops.

Ukraine’s fertile fields have turned it into a big agricultural supplier too. Two-thirds of its arable land is used for agriculture.

The UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) lists Ukraine as one of the world’s largest producers of wheat, corn, sunflower seeds, barley, sugar beet, potatoes and soybeans in 2020. The total value of these crops in Ukraine in 2020 was $21.4bn. It’s also the world’s third-largest producer of potatoes and pumpkins.

Ukraine is also the biggest producer of sunflower seeds, providing over a third of global supply. As a consequence, sunflower oil has risen in price by over 25% since the war started. Sunflower seeds and sunflower oil are an essential ingredient in many food production processes, and are among the most exported agricultural commodities.

Russia and Ukraine are also responsible for 29% of globally traded barley and 15% of maize.

The globalisation of agriculture

The most exported agricultural products nowadays include wheat, rice, corn, barley, rapeseed, soybeans, sunflower seeds, palm oil and bananas. Some of those crops are particularly suited to specific climates. Whereas wheat is a versatile crop grown across Europe, Asia and North America, bananas are better suited to tropical regions.

Globalisation has led to some climate-specific crops being domesticated in foreign markets. Technological advances in agriculture mean that some plants can be cultivated in non-native soils, while transportation allows other crops to be taken to far-flung markets. A study in 2016 found that more than two-thirds of agricultural products in the world’s national diets originated from a far-away region.

Source: The University of the Potomac.

Cereals are particularly versatile crops, and can be cultivated in a range of climates. Corn is the most produced agricultural commodity globally (1.1bn tonnes of the crop were produced in 2020), followed by wheat with 760.9mn tonnes and rice (756.7mn tonnes).

Agricultural superpowers

Agriculture accounts for 4.3% of global GDP. But with the effects of climate change (such as unseasonably heavy rains during planting season in China and a heatwave in India), geopolitical crises (such as the war in Ukraine) and an apparent trend for deglobalisation and protectionism, this figure is in jeopardy. And with supply of domesticated crops set to drop, price rises risk creating mass malnutrition or starvation.

Russia is one of the world’s five biggest food producers. In addition to encouraging Russia to lift its blockade of the Black Sea and finding alternative ways to export Ukrainian crops, the remaining agricultural superpowers must lift barriers to trade in the interests of global food security.

In 2020, half of global agricultural production came from Asia. China and India are both crucial players in agriculture. Both are top ten countries for agricultural exports too.

China is the world’s biggest wheat producer, producing 134.2mn tonnes of wheat in 2020 alone, worth $53.4bn. Much of that wheat is reserved for China’s domestic market, however. India, meanwhile, is the second-largest producer, harvesting over 107.5mn tonnes of the cereal in 2020. They will therefore be the most important players in plugging any Russia-sized gap which could develop in the global wheat market.

In 2020, China was the top producer of more than 30 crops, including tomatoes, rice and potatoes. Rice is China’s most produced crop overall – totalling 353.1mn tonnes in 2020. In 2020, China’s agricultural production was valued at $1.1 trillion, a record high. Because it produces 25% of the world’s grain, China is a key player in global food security.

The US, meanwhile, is the world’s largest agricultural exporter, with exports valued at $147.9bn in 2020. In particular, it is a big exporter of corn, rice, wheat, sorghum and apples.

Notably, the US is the world’s biggest grower of corn, producing around $52bn worth of the crop per year, according to the University of the Potomac. In combination, the US, China and Brazil grow about two-thirds of the world’s corn.

There are other crucial players for specific crops too: Germany is the world’s biggest producer of milk, while Latin American countries lead the world in sugarcane harvests.

The temptation for these agricultural powerhouses will be to place restrictions on food exports as the prospects for food security continue to worsen. Indeed, over 20 countries have already imposed export bans on certain agricultural commodities, including Turkey and Argentina. To overcome the danger of millions going hungry, they must do the opposite, and relax restrictions on trade. Indonesia recently lifted a ban on exporting palm oil, a promising precedent. Officials around the world will hope that this is the beginning of a détente, not the exception which proves the rule.

Data

Ruble strengthens as sanctioned oil companies repatriate cash

The Russian ruble strengthened after the Trump administration imposed oil sanctions on Russia’s leading oil companies, extending a rally that began after the Biden administration imposed oil sanctions on Russia in January.

Russia's central bank cuts rates by 50bp to 16.5%

The Central Bank of Russia (CBR) cut rates by 50bp on October 24 to 16.5% in an effort to boost flagging growth despite fears of a revival of inflationary pressure due to an upcoming two percentage point hike in the planned VAT rates.

Ukraine's trade deficit doubles to $42bn putting new pressure on an already strained economy

Ukraine’s trade deficit has doubled to $42bn as exports fall and imports balloon. The balance of payments deficit is starting to turn into a serious problem that could undermine the country’s macroeconomic stability.

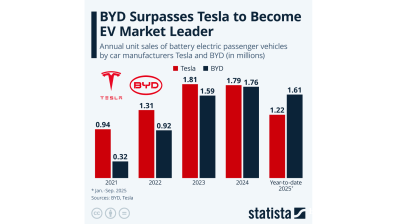

BYD surpasses Tesla to become EV market leader – Statista

While Chinese manufacturer BYD already pulled ahead of Tesla in production volume last year, with 1,777,965 battery electric vehicles (BEV) produced in 2024 (4,500 more than Tesla), the American manufacturer remained ahead in sales.