As was long expected, the Kyrgyz parliament voted unanimously on September 25 to dissolve itself, setting up snap elections for later this autumn almost exactly a year ahead of schedule.

Parliament Speaker Nurlanbek Turgunbek uulu told reporters he expects the elections to fall around November 30, but President Sadyr Japarov will set the official date in the coming days.

The deputies who initiated the measure said they want to better space out the parliamentary and presidential elections. Parliamentary elections had been slated to take place in November 2026 with the presidential election following in mid-January 2027.

“That sort of situation could lead to political instability,” Deputy Ulan Primov said during a committee hearing September 23. “Additionally, running two election campaigns in a row will require significant material resources and create the risk of violations of the law.”

The idea for early elections likely came from President Japarov and powerful security chief Kamchybek Tashiev, rather than the parliament itself, said Medet Tiulegenov, a political science professor at Ala Too International University in Bishkek.

“Normally for consolidated regimes and political systems like ours, change and upheaval are unlikely to take place as everything stays under control. The only shock points are elections, so they want to get through those smoothly,” he said.

Since Japarov came to power after mass protests in 2020, the parliament, officially named the Jogorku Kenesh, has transformed from a raucous body willing to challenge the executive branch into a docile rubber-stamp body, a trend in line with the country’s broader democratic backsliding during Japarov’s tenure.

Political forces loyal to the country’s governing duo, Japarov and Tashiev, exert overwhelming influence over the current parliament, elected in 2021, and few expect the new elections to change that.

“We don’t have an opposition, in fact, and parliament doesn’t look like a place you could put one together,” Tiulegenov told Eurasianet. “Accordingly, the parliament is not a threat to the president, at least currently.”

There is a tiny handful of liberal and conservative deputies who critique, and occasionally vote against, government policy. But they never directly criticise the administration and assiduously avoid the “opposition” label.

The risks of confrontation have been made clear over the last year. Deputy Sultanbay Ayzhigitov, a conservative nationalist, was booted from office in March after he harshly panned a border deal with Tajikistan as too generous, criticising it to Tashiev’s face during a session of parliament.

The Social Democratic Party of Kyrgyzstan (SPDK), which ran the country from 2010 to 2020, has largely been dismantled. In April, a court found three of its leaders guilty of vote buying in last year’s local elections and barred them from political participation. In June, a court sentenced exiled former Social Democratic president Almazbek Atambayev in absentia to 11 years in prison in connection with a 2019 shootout at his family compound.

Lawyers for the SDPK defendants have characterised the charges as politically motivated, and the cases are being appealed, though that did not stop security forces from seizing Atambayev’s property on September 13.

Leading politicians previously had denied early elections were on the cards despite persistent rumours to the contrary—until parliament returned for a new session in September. Questioned about his past statements denying there would be early elections, Turgunbek uulu, the Parliament Speaker, quipped “in this world only the holy Koran is unchanged.”

Other supporters said early elections were needed to legitimise parliament after lawmakers passed an overhaul of the election system earlier this year. Previously, 36 of the parliament’s 90 deputies were elected from single-member districts and the rest were elected proportionally from party lists. Now, all 90 deputies will be elected from 30 three-member districts.

The new system may lower minority and female representation, weaken the influence of the country’s already ephemeral political parties and tilt the scales toward richer candidates who can mount a campaign without the support of a party list, Tiulegenov said.

At the same time, it could make the elections less predictable and might let a few more critical voices slip through, he said. “There’s some intrigue on the microlevel.”

This article first appeared on Eurasianet here.

Alexander Thompson is a journalist based in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, reporting on current events across Central Asia. He previously worked for American newspapers, including the Charleston, S.C., Post and Courier and The Boston Globe.

News

Armenia’s Pashinyan sets out EU membership goal in UN speech

Armenia now the most Western-leaning of the three South Caucasus states as region's geopolitical balance shifts.

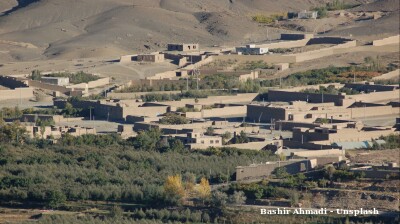

China, Russia, Pakistan and Iran push back on Trump ambitions in or near Afghanistan

Trump’s administration has been exploring options for keeping a military footprint in Afghanistan - a move that Russia has already said would have catasrophic consequences.

Germany preparing to enter direct negotiations with Afghanistan’s Taliban government

It has also been speculated that Germany might be readying to accept a liaison presence on the part of the Afghan government, that stops short of full recognition.

Croatian PM angrily rejects Hungarian accusations of war profiteering

"We're the good guy," says Andrej Plenkovic after Hungarian foreign minister claims Zagreb is profiting from disruptions in Russian supplies.

_1758916725.jpg)