Hundreds of delegates gathered in the legendary Silk Road city of Samarkand in Uzbekistan on November 3 for the second Uzbekistan Economic Forum to learn about the progress the country has made during these crisis years and its plans for the future.

Uzbekistan's first five-year transformation plan has come to an end, and this conference launches the second “New Uzbekistan” plan that will run to 2026. The first plan has been very successful, with economic activity visibly picking up in about 2018, but the new plan is supposed to deliver a root-and-branch transformation of the economy into a fast growing market economy driven by the inflow of private capital from domestic and international sources.

The key message, and indeed the theme of the whole conference, was inclusive “reforms for the people.” Uzbekistan has one of the youngest populations in the FSU with an average age of 29 years. It is also the fastest growing population in the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). Since 1991 at the end of Soviet Union the population of 20mn has grown to 36mn now and in the next three years it will overtake both Poland and Ukraine in terms of numbers of inhabitants before hitting 70mn by 2050.

That demographic explosion, especially in the context of the demographic collapse that is happening in nearly every other country in Eurasia, including Russia and the EU, could be the basis of decades of strong growth. But it also presents a challenge to the government to provide jobs for its swelling youth.

Anna Bjerde, the Vice President of the World Bank, emphasised that social issues – education and health chief among them – are one of the bank’s top three focuses for the coming years.

In his address in the opening session of the congress, President Shavkat Mirziyoyev highlighted that a key part of the social programme, that is also part of the government’s heavy ESG focus, is to reduce poverty by 50% by 2030. Poverty has already been reduced from 22.8% in 2018 to under 16% now and less than 5% compared to the global poverty line, the World Bank said.

The World Bank has thrown itself into the same programmes and added that incomes are also supposed to double to $4,000 a month. Currently Uzbekistan per capita income is about a tenth of those in the more prosperous, petro-fuelled, Kazakh economy.

“We need to improve the quality of life, which means a large-scale government social support programme that will affect each and every Mahalla, with new roads, clean water supplies, schools and hospitals,” Mirziyoyev said, referring to the local community councils that the Uzbek government has revived as the most efficient way to directly react to local community problems and demands on a daily basis.

Of the eight goals outlined by Mirziyoyev, six are related to the social sphere and only two to more general economic reforms: the need to stabilise the economy in the face of global uncertainty that should deliver on 5% growth for years; and to invest into infrastructure, logistics and trade relations with all Uzbekistan’s international partners, but especially those in the region.

Deals

At the first conference in Tashkent last year over a billion dollars worth of deals were signed, including the flagship privatisation of the Coca-Cola factory that was set up in 1990s. At the same time, many investment deals were signed then with Russian companies and banks which were active in the country.

This year there were much fewer deals, as investors have been spooked by the global uncertainty caused by the unfolding polycrisis. A flagship privatisation of the Fergana Azot fertiliser company was due to be signed and Prime Minister Aripov said that the talks were all but concluded, however, the potential buyers had asked for a two-week delay until October 28 as they had more details they wanted to check. But the sale is expected to be close before the end of the year as the privatisation process continues.

Private economy

Privatisation and reforms were a constant theme in the talks as the government plan is to shift to funding the economy using private capital.

The growing realisation that the global crisis is here to stay, as bne IntelliNews recently detailed in a cover feature, the Fractured World, the cost of borrowing has gone up while investors’ risk appetite has gone down, which means funding the government using international capital markets has become unrealistic in the foreseeable future. That leaves foreign direct investment (FDI) as the main source of new funds and making Uzbekistan’s effort to privatise its economy even more important.

There are several IPOs on the docket in the coming year, including UzAvto, the main carmaker, the UzMetal metallurgical complex, USM, a publically owned telecoms asset, and possibly the jewel in the crown, the state-owned Navoi Gold giant, the biggest contributor to the state budget.

“There are 15 IPOs on the list for the next year, but even if they manage to get five away that would be a major success,” says Karen Sharipov, of Avest Invest, a local brokerage and boutique investment bank.

It’s an ambitious plan, but will be difficult in the current environment. However, even if it goes slowly, unlike most countries in Eurasia, apart from a dip in 2020 caused by the start of the pandemic, Uzbekistan has managed to maintain strong growth throughout the crisis and is still on course to expand by around 6% this year – making it one of the fastest growing countries in the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS).

This good performance means that despite expanding spending during the coronacrisis the government is still running an only modest 3% GDP deficit and has a very modest 40% of debt/GDP ratio.

“Unlike most people Uzbekistan has managed to maintain its fiscal buffers, leaving it in a strong position versus the other countries in the region if there are more shocks,” says the IMF.

Inflation vs growth

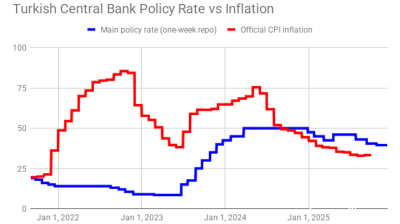

The perennial theme in all the financial talks was the battle with inflation and the trade-offs with the refraining from rate hikes in order not to crash the economy.

Uzbekistan is suffering from high inflation like everyone else, which was running at over 12% in October. In his session the governor of the central bank, Ilkhomjon Abdugafarov, explained that the regulator had adopted inflation targeting for the first time after the new team took over following President Shavkat Mirziyoyev’s election in 2017, “but it will take time to put all the tools in place.” The goal is to anchor inflation expectations that have always been untethered.

The central bank is targeting 5% inflation and was on course to achieve that target in 2022, but its goals have been blown up by the polycrisis. Used to unstable prices for almost the entire history of the Republic’s modern existence, Abdugafarov has an uphill battle winning the trust of the people, but recently the regulator won kudos by revising its target and after it hit a new interim target of 10% inflation this year the central bank won badly needed respect from the population.

The outlook for Uzbekistan is bright, but the challenges it faces are formidable. Happily, the prudence of the government and the central bank means the economic is sitting on a solid foundation with resources enough to weather more shocks and setbacks in the fractured world, so it has time on its side.

Features

US denies negotiating with China over Taiwan, as Beijing presses for reunification

Marco Rubio, the US Secretary of State, told reporters that the administration of Donald Trump is not contemplating any agreement that would compromise Taiwan’s status.

Asian economies weigh their options amid fears of over-reliance on Chinese rare-earths

Just how control over these critical minerals plays out will be a long fought battle lasting decades, and one that will increasingly define Asia’s industrial future.

BEYOND THE BOSPORUS: Espionage claims thrown at Imamoglu mean relief at dismissal of CHP court case is short-lived

Wife of Erdogan opponent mocks regime, saying it is also alleged that her husband “set Rome on fire”. Demands investigation.

Turkmenistan’s TAPI gas pipeline takes off

Turkmenistan's 1,800km TAPI gas pipeline breaks ground after 30 years with first 14km completed into Afghanistan, aiming to deliver 33bcm annually to Pakistan and India by 2027 despite geopolitical hurdles.