The Democratic Republic of the Congo is offering the United States significant mining rights in exchange for military support. In February 2025, President Félix Tshisekedi wrote to President Donald Trump asking for help pushing back the M23 rebel group. It is using access to cobalt, copper and lithium as leverage.

The country – with a land mass two-thirds the size of Western Europe – holds an estimated $24 trillion in untapped mineral wealth and produced 244,000 tonnes of cobalt in 2024, almost 80% of the global supply. The deal could help Kinshasa reduce its dependence on China and open the door for American investment in one of the world's most strategic mining markets.

Officials in Washington have signalled a willingness to consider multibillion-dollar investment in return. The discussions form part of a broader push to stabilise the country's eastern areas, where armed groups backed by Rwanda have disrupted mining zones, and to secure new supplies of battery metals as demand for electric vehicles and energy infrastructure accelerates. Any agreement would break from decades of limited engagement by American companies in central African mining.

Much of the mineral production is concentrated in the southern provinces of Haut-Katanga and Lualaba, where established industrial operations operate alongside thousands of artisanal miners. Exploration has expanded rapidly in recent years, with the country attracting more than $130mn in exploration investment in 2024. In the same year, it secured $1.8bn in foreign direct investment (FDI), making it one of the most attractive African states.

Yet vast areas remain underdeveloped, particularly in the east, where insecurity, poor roads and overlapping concessions deter formal investment. North Kivu and Ituri are thought to hold significant untapped reserves but are among the most volatile.

Cobalt is essential to lithium-ion batteries in electric vehicles (EVs), while copper underpins power grids, electric motors and charging infrastructure. By 2030, global cobalt demand is expected to double – driven by battery applications in EVs – and the DRC is forecast to contribute 44% of the supply growth, creating immense opportunity for the country.

Lithium and tantalum – of which the DRC is also a leading producer – are critical to semiconductors, smartphones and defence applications. As global demand intensifies and supply chains tighten, Kinshasa faces increasing pressure to scale up production, strengthen governance and broaden its investor base beyond Chinese state-backed operators.

The DRC dominates global cobalt reserves, holding 6mn tonnes out of a total of 11mn tonnes worldwide, according to the US Geological Survey (USGS). Australia and Indonesia follow with 1.7mn tonnes and 500,000 tonnes respectively. The DRC is also home to two of the largest cobalt mines globally – Tenke Fungurume (3.34mn tonnes) and Kisanfu (1.91mn tonnes). Two other mines Mutanda and Kamoto also hold significant reserves.

In copper, the DRC boasts some of the richest ore bodies in the world. Grades exceed 2.5%, more than four times the global average and eight times higher than at Morenci, the largest copper mine in the US. Copper's critical role in EV batteries and other green energy technologies has led some to call it 'the new oil', and the DRC is dubbed 'the Saudi Arabia of electric vehicle age'. The global thirst for copper is expected to jump by 20% by 2035 due to burgeoning demand from EVs, electricity transmission grids and renewable power generation.

The country also has vast coltan reserves and is a significant, though underdeveloped, source of lithium. Manono-Kitolo, in the southern province of Tanganyika, is believed by some to be the world’s largest lithium deposit. It contains an estimated 120mn tonnes of lithium ore grading 0.6%, yielding around 720,000 tonnes of lithium. Despite its suitability for large-scale open-cast mining, the project remains stalled due to a dispute between China’s Zijin Mining and Australia’s AVZ Minerals.

The DRC is often described as the world's most prosperous country in terms of natural resources. It hosts more than 1,100 different minerals and precious metals – including tin, tungsten and tantalum – and is also the world's fourth-largest diamond producer.

However, the US has historically under-invested in its commercial relationship with the DRC, particularly in the mining sector. The Export-Import Bank of the US (EXIM) offers no coverage for the DRC, while the Development Finance Corporation (DFC), Washington's development finance institution, has focused narrowly on the Lobito Corridor – an initiative facing its own challenges.

US support in the DRC has primarily taken the form of traditional development aid, focusing on health and education rather than strategic commercial engagement. While these efforts are important, they have done little to advance trade, investment or mineral security goals.

China has a dominant interest in the DRC's mining sector. The most significant mining projects include the Kamoa-Kakula copper project, Tenke Fungurume mine and Kamoto copper. The Kamoa-Kakula copper project is owned by a joint venture comprising Ivanhoe Mines (39.6%), Zijin Mining Group (39.6%), Crystal River Global (0.8%) and the DRC government (20%). The project is among the world's most significant undeveloped high-grade copper discoveries, with measured resources of 90mn tonnes at 3.13% copper and probable mineral reserves of 235mn tonnes.

The mine started producing concentrates in May 2021, with commercial production beginning in July 2021. It is being advanced through a phased approach, with peak production estimated at 800,000 tpy. This would make the project the second-biggest copper complex globally.

The Tenke Fungurume mine is a copper-cobalt project owned by Chinese private holding company CMOC (80%) and Gécamines (20%).

CMOC acquired controlling interests in the mine in 2017 in a $3bn transaction, and in August 2021 it announced plans to double production with a $2.51bn investment. The investments will raise output from 183,000 tpy of copper to 383,000 tpy, and from 15,400 tpy of cobalt to 32,400 tpy, bringing total mineral production to 415,400 tpy. It is the world’s second-largest cobalt mine.

The Kamoto Copper Company (KCC) is owned by a joint venture comprising Glencore (75%), Gécamines (20%) and Simco (5%). It is the largest active cobalt mine in the world. KCC owns two open-cast mines (KOV and Mashamba East), one underground mine (Kamoto concentrator) and the Luili refinery in Kolwezi. KCC targets an annual nameplate capacity of 300,000 tonnes of copper and 30,000 tonnes of cobalt, bringing total mineral production to 330,000 tonnes.

Over the past two decades, China has seized the opportunity to fill the vacuum left by American absence from the country. The landmark 2007 Sicomines deal – a resource-for-infrastructure agreement – granted Chinese companies access to copper and cobalt in exchange for a $3bn infrastructure commitment. The deposits near Kolwezi – one of the DRC's most important mining regions in the south of the country – are estimated to be worth around $93bn.

China's dominance was further cemented in 2016 when US-based Freeport-McMoRan sold its majority stake in Tenke Fungurume (TFM) – the world’s largest cobalt mine and seventh-largest copper mine – to China Molybdenum Company (CMOC).

Freeport, heavily indebted following misjudged oil and gas acquisitions before the 2014 price crash, announced the $2.65bn sale in May 2016. Canadian firm Lundin Mining, which held a 24% stake, declined its right of first refusal. CMOC stepped in, backed by $1.59bn in financing from six Chinese banks, including state-owned giants such as the Bank of China and China Development Bank. It then facilitated the purchase of Lundin's stake by Hong Kong-based BHR, which used $700mn in Chinese bank financing. CMOC later took over BHR's interest, securing 80% control of TFM. Gécamines, the DRC's state miner, retained 20%. Chinese state-owned banks financed $2.48bn of the $2.68bn in credit used for the TFM deal (adjusted to 2021 prices).

Washington’s failure to contest the TFM sale is arguably the most significant commercial misstep it has made in Africa. Today, China owns or holds stakes in 15 of the DRC's largest copper and cobalt mines. That grip may tighten further. Glencore, the country's last major Western mining investor, is reportedly weighing the sale of its $6.8bn Mutanda and Kamoto operation – raising the prospect of another strategic asset falling into Chinese hands.

Moreover, as of April 2025, the DRC is battling its most serious escalation of violence in years, with the M23 rebel group launching a renewed and highly coordinated offensive in the east. Since January, the group has overrun large parts of North and South Kivu, seizing control of strategic cities including Goma and Bukavu. The offensive has killed an estimated 7,000 people and displaced more than 450,000, triggering a humanitarian crisis and threatening regional stability.

The latest outbreak marks a significant shift in the conflict's scale and sophistication. M23, composed mainly of Congolese Tutsi fighters, is widely believed to be receiving direct military support from Rwanda – including the deployment of an estimated 4,000 Rwandan troops. Kigali denies involvement, but satellite imagery and intercepted communications suggest otherwise. The DRC accuses Rwanda of seeking control over key mineral zones, including coltan, gold and cobalt areas.

Facing mounting pressure on the battlefield, President Tshisekedi has turned to Washington, offering mineral access as leverage for security support. The move highlights the severity of the current conflict and Kinshasa's effort to shift away from reliance on Chinese and Rwandan-backed operators in the mining sector.

Meanwhile, peace talks in Doha between Kinshasa and M23 have stalled, with both sides unwilling to compromise. With tensions rising and the Congolese military stretched thin, there are growing fears that the conflict could spill across borders and further destabilise the Great Lakes region.

The latest Tshisekedi proposed deal offers Washington an opening in a market it has long neglected. While concerns over Beijing’s dominance have intensified, American firms have remained marginal players in the Congolese mining sector.

That began to shift at the start of December 2024 when President Joe Biden visited Angola to promote the Lobito Corridor – a $4bn rail and port project aimed at channelling copper and cobalt from central Africa – including the DRC – to global markets through the Port of Lobito, the Angola harbour located on the Atlantic Ocean. Backed by the US and other G7 partners, the corridor is a strategic alternative to Chinese-dominated logistics.

It is the most substantial American-led infrastructure initiative in the region in decades. An additional $600mn in funding was pledged during Biden’s visit, and US diplomats confirmed in April 2025 that financing remains on track. The goal is to streamline mineral exports from Zambia and southern DRC, improving transparency and making the region more attractive to Western investors. If successful, the corridor could shift trade patterns and reduce reliance on routes controlled by state-linked Chinese companies.

It is unclear whether the Trump administration will back the project with the same enthusiasm as the Biden one. Trump’s Africa advisers have favoured more direct exchanges – military or diplomatic support in return for resource access – and Tshisekedi’s proposal appears to follow that logic. Discussions with Kinshasa have referred to investments worth several billion dollars, though no agreement has yet been reached. The Congolese side is pressing for clear timelines and deliverables.

Kinshasa’s latest proposal reflects a broader shift in Washington's approach to mineral diplomacy. Under Trump, securing access to strategic resources has become a core objective, often structured as quid pro quo arrangements. The president's advisers have openly framed resource access as a foreign policy priority, particularly in countries where traditional development models have struggled.

In echoes of the Great Game that once played out between Britain, Russia and other powers in Central Asia, China has also announced plans to invest $1.4bn in the ageing railway that links Dar es Salaam in Tanzania with Zambia's Copperbelt. The investment was unveiled on 20 March 2025 during the Zambia International Mining and Energy Conference. Under a trilateral deal with Tanzania and Zambia, the China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation (CCECC) will rehabilitate the 1,860-km TAZARA line over three years and operate it for 30 years. The agreement includes $1bn for infrastructure upgrades and $400mn for new rolling stock, including 32 locomotives and 762 wagons.

Originally built with Chinese support in the 1970s to bypass white-ruled southern Africa, the TAZARA line remains a strategic outlet for Zambian copper exports via the Indian Ocean. It terminates at Kapiri Mposhi, connecting with Zambia's north-south rail grid and facilitating indirect freight access to the DRC. However, there is no dedicated spur from TAZARA into the DRC, and the upgraded route is not expected to extend across the border. Nonetheless, the line passes within the logistical range of the DRC frontier, keeping the possibility of future linkages to one of Africa's most mineral-rich regions open.

Whether any agreement between the US and the DRC moves forward will depend on risk mitigation. American companies remain cautious about operating in volatile jurisdictions without guarantees. Political risk insurance, development finance backing and credit support are likely prerequisites. Unlike Chinese state-linked firms, US investors avoid unstable regions unless underwriting and logistical support are in place. That presents a hurdle, particularly in eastern provinces where infrastructure remains poor and violence persists.

Furthermore, Ademola Adesina, the co-founder and president of Sabi, a Nigerian company that connects African small-scale and artisanal miners with global buyers, said in a recent article in Semafor that the real opportunity lies in working with artisanal and small-scale miners in Africa, who play a crucial role in the global critical minerals supply chain. In the DRC, such small-scale operations contribute up to 30% of the world's cobalt supply.

"Across the continent, two-thirds of lithium supplies come from small-scale miners, as does 60% of the global supply of tantalum," he writes. "If scaled, small-scale mining operations could more than meet the needs America’s domestic production can’t achieve alone. The work of these operators could be boosted through targeted investment, transparent logistics and predictable payment structures that meet US regulatory and technical standards."

He adds that the US government can help upgrade production capacity while ensuring compliance and traceability by establishing direct purchasing relationships and deploying financing and technical assistance.

Whether Washington ultimately seizes the opportunity offered by Tshisekedi remains uncertain. But with the stakes rising – from the electrification of the global economy to the remilitarisation of the DRC’s east – the case for a strategic pivot is clearer than ever. The DRC could finally be forcing the US to choose – act or watch the world’s most critical mineral reserves fall further under its main rival’s control.

Features

Southeast Asia welcomes water festivals, but Myanmar’s celebrations damped by earthquake aftermath

Countries across Southeast Asia kicked off annual water festival celebrations on April 13, but in Myanmar, the holiday spirit was muted as the country continues to recover from a powerful earthquake that struck late last month

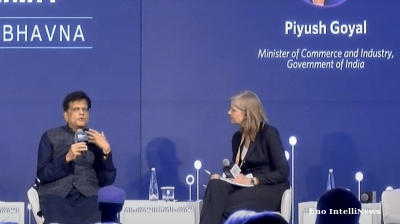

India eyes deeper trade ties with trusted economies

India is poised to significantly reshape the global trade landscape by expanding partnerships with trusted allies such as the US, Indian Commerce and Industry Minister Piyush Goyal said at the Carnegie India Global Technology Summit in New Delhi

PANNIER: Turkmenistan follows the rise and rise of Arkadag’s eldest daughter Oguljahan Atayeva

Rate of ascent appears to make her odds-on for speaker of parliament role.

Farm to front line: Ukraine's wartime agriculture sector

Despite the twin pressures of war and drought, Ukraine’s agricultural sector continues to be a driving force behind the country’s economy, with experts confident of continued growth and investment.