Countries across Southeast Asia kicked off annual water festival celebrations on April 13, but in Myanmar, the holiday spirit was muted as the country continues to recover from a powerful earthquake that struck late last month, AP News reported.

The holiday, observed during the region’s hottest season, is typically marked by several days of festive water throwing, spiritual rituals, and family reunions. Temperatures can soar above 40°C (104°F), making the celebrations both symbolic and practical. In Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Myanmar, the water festivals coincide with the traditional New Year and draw more than 1mn to both rowdy street parties and solemn cultural ceremonies.

In Myanmar, the festival is known as Thingyan. This year’s event follows a devastating 7.7 magnitude earthquake on March 28 that killed more than 3,600 people and damaged buildings ranging from modern apartments to centuries-old pagodas in the country’s central region. Adding to the toll, a 5.5 magnitude aftershock struck central Myanmar on April 13—one of the strongest tremors since the initial quake.

Even before the disaster, celebrations were expected to be subdued amid the ongoing civil conflict following a 2021 military coup and the deepening economic crisis. The country also saw Thingyan cancelled in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Even so, the holiday offered a rare opportunity for many to pause. Notably, this year's Thingyan was the first celebrated after its inclusion on UNESCO's Intangible Cultural Heritage list in December. However, the usual vibrant festivities were muted this year, as Myanmar's military authorities requested a peaceful and traditional observance without singing and dancing, out of respect for the national mourning period following the earthquake.

While festival goods like water guns remained on sale, government-organised events were cancelled. In Yangon, large festival pavilions and decorations near City Hall were dismantled, and the typically vibrant downtown area was noticeably quiet. People’s Square, a regular hub for public festivities in Yangon, will not host events this year. Only modest signs of celebration could be seen in residential neighbourhoods, where children played quietly with water, and elderly citizens visited pagodas for prayers and merit-making.

In the country's capital, Naypyitaw, state media reported that a number of subdued cultural events would mark UNESCO’s recognition of Thingyan. These include traditional rituals such as applying thanaka—a cosmetic paste made from tree bark—and ceremonial acts like gently washing elders’ heads and trimming their nails, as well as food donations.

In contrast, neighbouring Thailand began its Songkran festival with the usual exuberance. The holiday triggers a nationwide migration, as workers leave Bangkok to return to their hometowns, often stretching the official three-day holiday into a full week.

Bangkok’s backpacker haven, Khao San Road, was expected to be a focal point for raucous water fights involving locals and tourists alike. Buckets and high-pressure hoses are commonly used, with moving vehicles often joining the fray. The holiday, traditionally linked to solar movement and the agrarian calendar, retains cultural rites such as washing Buddha statues and honouring elders, even amid the revelry.

However, Songkran also brings a surge in road accidents. Thailand, which already has one of the world’s highest traffic fatality rates, typically sees a spike in deaths and injuries during the festival due to increased travel and alcohol consumption.

In Cambodia and Laos, where the water festivals are known as Choul Chnam Thmey and Pi Mai Lao, respectively, celebrations were also underway, though generally smaller and less chaotic than Thailand’s.

Features

Minerals for security: can the US break China’s grip on the DRC?

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is offering the United States significant mining rights in exchange for military support.

India eyes deeper trade ties with trusted economies

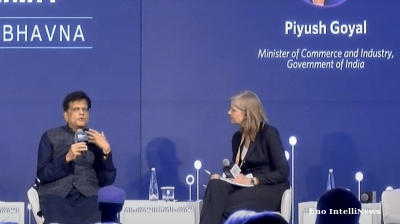

India is poised to significantly reshape the global trade landscape by expanding partnerships with trusted allies such as the US, Indian Commerce and Industry Minister Piyush Goyal said at the Carnegie India Global Technology Summit in New Delhi

PANNIER: Turkmenistan follows the rise and rise of Arkadag’s eldest daughter Oguljahan Atayeva

Rate of ascent appears to make her odds-on for speaker of parliament role.

Farm to front line: Ukraine's wartime agriculture sector

Despite the twin pressures of war and drought, Ukraine’s agricultural sector continues to be a driving force behind the country’s economy, with experts confident of continued growth and investment.