Governments in the Western Balkans are scrambling to respond to a deepening demographic crisis characterised by plummeting birth rates and a mass exodus of young people.

As forecasts paint a grim picture – a projected loss of 3mn people by 2050 – regional leaders are turning to immigration and financial incentives in a bid to stabilise their shrinking populations, says a report by the Centre for Eastern Studies (OSW). Yet experts warn that these measures fall far short of the comprehensive strategies needed to reverse long-term trends.

“The outlook is pessimistic,” says the OSW report. “Persistently low fertility rates and mass emigration significantly reduce the likelihood of reversing these negative trends, while government efforts to boost birth rates remain fragmented and largely ineffective.”

The six countries of the region – Albania, Bosnia & Herzegovina (BiH), Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia – have collectively lost nearly 2.5mn people in the past two decades. With over one in five citizens now living abroad, governments are increasingly relying on migrant labour to plug growing gaps in their workforces.

Labour gaps and immigration

Facing a shortfall of around 50,000 workers, Serbia has been the most active in streamlining immigration. In 2023, it issued 52,000 work permits, with the largest numbers going to Russians, Chinese, Turks and Indians.

Albania, Bosnia and Montenegro are also reporting severe shortages, especially during peak tourist seasons. These countries are increasingly turning to workers from South and Southeast Asia, including Nepal, Bangladesh and the Philippines.

Montenegro is the only Western Balkan country currently seeing a slight population uptick, a result of immigration by Russians, Turks and Ukrainians fleeing war or economic instability.

Cash incentives for babies

Governments have introduced a patchwork of pronatalist policies, mostly focused on one-off financial incentives for new parents. In Serbia, parents receive up to €5,000 for a second child and even higher sums for third and fourth children, paid in instalments. A home subsidy programme was launched for families with children, though uptake has been minimal. “Due to numerous legal restrictions, only 583 Serbs have received these grants in the past two years,” the OSW found.

Despite this, other countries have followed suit. Montenegro recently raised its one-off birth grants to €2,500 for a fourth child and added monthly allowances of €30 per child until adulthood. Albania offers up to €1,200 for a third child, while Kosovo pays monthly child benefits of up to €90 for families with three children. North Macedonia provides up to €960 for a third child, and Bosnia offers between €250 and €500.

However, these financial stimuli are not addressing the deeper roots of the crisis. “The reasons why people in the Western Balkans choose to emigrate or decide not to have children are increasingly linked to structural and cultural changes,” the report argues.

“However, local political elites are generally uninterested in raising democratic standards, tackling corruption, or improving the judicial system and public services. In fact, the emigration of disillusioned citizens seeking genuine change and comprehensive reform often benefits the region’s leaders, as it helps to consolidate their power.”

Untapped diaspora potential

Some governments are also attempting to reframe their relationships with their large diasporas, traditionally seen as sources of remittances. In 2022, remittances made up as much as 13.4% of Kosovo’s GDP, with similarly high contributions across the region.

Countries like Kosovo and Albania have launched diaspora engagement strategies. Kosovo’s 2022-27 National Strategy identifies emigrants as key players in economic development, while Albania’s 2021-25 strategy focuses on mapping the diaspora and encouraging investment.

Still, OSW notes that “cooperation between the diasporas and the WB6 governments faces significant challenges”, primarily due to lingering distrust in institutions and an unfriendly business environment.

The clock is ticking

Meanwhile population ageing is accelerating. Bosnia and Serbia now have 20% of their populations aged 65 or older, with the rest of the region not far behind. Only Kosovo, with its relatively young population, is an exception, though it too has already slipped below the UN’s long-term population forecast.

The economic cost of this crisis is high. The region’s competitive edge – a young, skilled and cheap labour force – is eroding. According to the World Economic Forum, Bosnia ranks among the worst globally for talent retention, with a score of just 1.8 out of 7. North Macedonia, Serbia and Albania score only slightly better.

While immigration offers a short-term fix, the report warns that only comprehensive reforms aimed at improving governance, services and the quality of life can prevent further decline.

However, it argues, this may not be in the interests of the ruling elites. “Local political elites are generally uninterested in raising democratic standards, tackling corruption, or improving the judicial system and public services. In fact, the emigration of disillusioned citizens seeking genuine change and comprehensive reform often benefits the region’s leaders, as it helps to consolidate their power,” OSW analysts wrote.

Yet without such change, the Western Balkans risk becoming trapped in a vicious cycle of depopulation and underdevelopment.

Features

Minerals for security: can the US break China’s grip on the DRC?

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is offering the United States significant mining rights in exchange for military support.

Southeast Asia welcomes water festivals, but Myanmar’s celebrations damped by earthquake aftermath

Countries across Southeast Asia kicked off annual water festival celebrations on April 13, but in Myanmar, the holiday spirit was muted as the country continues to recover from a powerful earthquake that struck late last month

India eyes deeper trade ties with trusted economies

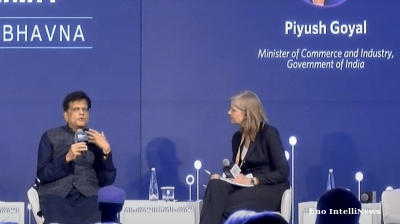

India is poised to significantly reshape the global trade landscape by expanding partnerships with trusted allies such as the US, Indian Commerce and Industry Minister Piyush Goyal said at the Carnegie India Global Technology Summit in New Delhi

PANNIER: Turkmenistan follows the rise and rise of Arkadag’s eldest daughter Oguljahan Atayeva

Rate of ascent appears to make her odds-on for speaker of parliament role.

_1744200906.jpg)