Russian oil refineries are not normally newsmakers, but they have found themselves on the front page recently as Ukraine’s new long-range drones have brought some of Russia’s oil infrastructure within striking distance, Sergey Vakulenko, an independent energy analyst and consultant to a number of Russian and international global oil and gas companies, said in a note for Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Several Russian refineries have been hit by drones or been the subject of suspected arson attacks in the last weeks, suggesting that Ukraine has changed tactics and is increasingly targeting Russia’s money-making oil sector.

“On one hand, the additional income Russia receives from exporting the products made by its refineries instead of the oil they are made from is relatively insignificant compared to what it makes from selling the crude oil. Ironically, Russia’s tax system means that the state loses money if energy companies export oil products instead of crude oil,” Vakulenko said.

“On the other, oil product exports allow Russia to target multiple segments of the global oil market. And, of course, refineries are crucial for both the Russian economy and waging war in Ukraine: cars, trucks, tractors, harvesters, tanks, ships and planes need gasoline, diesel and jet fuel; they cannot run on crude oil,” Vakulenko added.

As reported by bne IntelliNews, Ukraine fired its new long-range drones at the Ust-Luga petrochemical complex in Russia’s northwest, close to St Petersburg, that belongs to the privately owned Novatek energy giant. While Novatek is best known for producing and selling LNG, the Ust-Luga plant produces petroleum products such as naphtha and jet fuel from stable gas condensate, which are all exported. The drones caused a fire that has shut the plant down for at least week to effect repairs, but one drone narrowly missed hitting a full oil storage tank that could have caused devastating damage.

Then on January 25 another fire broke out at the Tuapse refinery on the Black Sea that belongs to Russian state-owned oil major Rosneft. The fire there was also quickly extinguished, but it was one of many energy infrastructure facilities hit by fire or drone attacks across Russia in the previous week.

The Tuapse refinery is the only large oil refinery in Russia located on the shores of the Black Sea and is one of the country's oldest, having been constructed in 1929. The plant's annual capacity is 12mn tonnes, or 240,000 barrels per day (bpd) and, like Ust-Luga, is largely focused on exports, serving Turkey, China, Malaysia and Singapore. It also produces similar petroleum products to those from Ust Luga: naphtha, fuel oil, vacuum gasoil and high-sulphur diesel.

On January 12 a fire broke out at the Kstovo oil refinery that belongs to Lukoil, Russia’s leading privately owned company, that unsettled traders, as it is another major producer. Western sanctions mean Lukoil may not be able to fix the faulty gas compressor for several months – not a couple of weeks as might have been expected before the war, says Vakulenko.

The Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) claimed responsibility for the attack, using new long-range drones to strike the plant that is some 1,000 km from Ukraine-controlled territory, Politico reported. Ust Luga is also about 600 km from Ukraine.

The attacks appear to be as much about curbing Russia’s ability to produce the petroleum products it needs to run the war in Ukraine as about reducing the amount of money it makes from exports, although the two refineries hit in the last week are both export-orientated.

More attacks are now anticipated on other refineries that are producing oil products for the domestic market.

“The two refineries attacked by Ukraine in January are export-oriented, and do not play a major role in the domestic market. However, if small drones with no more than 5 kilograms of explosives managed to reach Ust-Luga, which is 620 miles [1,000 km] from Ukrainian territory, this means there are a total of eighteen Russian refineries with a combined capacity of 3.5mn bpd (more than half the Russian total) that are possible targets,” says Vakulenko, who correctly predicted that the oil sanctions would fail shortly after they were introduced at the end of 2022.

Russia’s vulnerability to reduced supplies of oil products at home was highlighted by a fuel crisis last summer, when the domestic market was struck by a shortage of fuel that sent prices at the pump soaring.

While the prospect of kamikaze drones hitting oil refineries conjures up images of giant fireballs, in reality Russia’s refineries are much better protected from aerial attacks thanks to Soviet-era constriction codes.

“Russian construction codes – a relic of the Cold War – make refineries resilient against traditional air bombing. And they usually have plenty of firefighting equipment available,” says Vakulenko. “This means drones cannot destroy a whole refinery. They can, however, create a fire. And if they are lucky, managing to hit a gas fractionation unit, they may even be able to cause a bigger explosion.”

The fires at both refineries hit in the last week were put out quickly and while considerable damage was done, the two refineries are expected to come back online relatively quickly, says Vakulenko, albeit with a diminished capacity.

Since the fall of the Soviet Union Russia’s oil sector has been modernised, an effort that rapidly accelerated after the 1998 financial crisis. After the ruble fell to a quarter of its pre-crisis level, Russia’s oil companies became cash cows as their costs, in rubles, were cut by three quarters, but their revenue, in dollars, remained the same. More was invested into the Russian oil companies in 1999 than in all the preceding decade.

Russia’s oil sector became heavily dependent on imported technology, a trend that was abruptly halted in 2022 following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, which dismantled the globally integrated model, raising concerns about Russia's long-term industrial sustainability in isolation.

The lack of access to technology may prove to be a very big problem at Lukoil’s Kstovo refinery due to a defective gas compressor that caused the fire, according to media reports.

“Lukoil will almost certainly experience significant difficulties in integrating non-original parts. In a worst-case scenario, the refinery may even need to acquire entirely new equipment,” says Vakulenko. “It’s true that gas compressors are not particularly complicated machines, and they are produced by Russian and Chinese factories. But that will not solve Lukoil’s problem – just like you can’t replace a faulty clutch in a BMW with a similar part from a Russian-made Lada, the same applies in industry. And “making do” with what’s available creates a host of knock-on problems.”

One significant hurdle for Lukoil, and likely for the Tuapse and Ust-Luga refineries as well, will be obtaining repair approvals from Russian safety oversight bodies. Current regulations demand adherence to original manufacturers’ specifications and parts for repairs, a challenging feat when original equipment manufacturers won’t sell their parts to Russia due to sanctions.

The upshot is that while Ukraine’s drones are not powerful enough to destroy Russia’s refineries, they are cheap to produce and Ukraine has them in large quantities, so they are capable of a sustained campaign of “nuisance attacks”, said Vakulenko.

“With a bit of luck, they can damage not just pipelines but also compressors, valves, control units and other pieces of equipment that are tricky to replace because of sanctions,” he added.

The new strategy of targeting Russia's oil infrastructure represents a new and serious challenge to Russia’s industrial resilience and increases the pressure on the economy to supply the war machine. While Russia boasts a larger industrial base than Ukraine, the former's international isolation means that making repairs is much more difficult, so that even nuisance attacks can have a significant impact on the Kremlin’s ability to supply its military.

“If we are seeing the beginning of a wave of attacks on western Russia’s oil refineries, the consequences will be serious. Either way, Russia’s reserves of resilience and ingenuity look set to be severely tested. The speed and quality of the repairs at Kstovo, Ust-Luga and Tuapse will be key indicators of Moscow’s readiness,” Vakulenko concluded.

Features

Minerals for security: can the US break China’s grip on the DRC?

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is offering the United States significant mining rights in exchange for military support.

Southeast Asia welcomes water festivals, but Myanmar’s celebrations damped by earthquake aftermath

Countries across Southeast Asia kicked off annual water festival celebrations on April 13, but in Myanmar, the holiday spirit was muted as the country continues to recover from a powerful earthquake that struck late last month

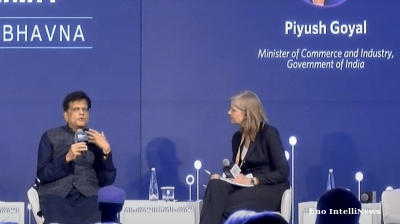

India eyes deeper trade ties with trusted economies

India is poised to significantly reshape the global trade landscape by expanding partnerships with trusted allies such as the US, Indian Commerce and Industry Minister Piyush Goyal said at the Carnegie India Global Technology Summit in New Delhi

PANNIER: Turkmenistan follows the rise and rise of Arkadag’s eldest daughter Oguljahan Atayeva

Rate of ascent appears to make her odds-on for speaker of parliament role.