It’s 11 days since an armed Serb gang shot dead a Kosovan border guard then holed up in a nearby monastery until they were overwhelmed by Kosovan security forces. The incidents took place around the village of Banjska, some 10km from the city of Mitrovica that has long been divided between the ethnically Serb north and Albanian south.

Crossing the river Ibar into north Mitrovica, over the bridge that has become a symbol of the divided city, dozens of red, white and blue Serbian flags adorn King Peter 1 street. Although all of the city lies within Kosovo, the Serbian flags are strung like bunting from side to side of the main street, and billow from lamp posts. The red, white and blue are painted onto murals and incorporated into shop signs.

North Mitrovica is considerably more subdued than the southern part of the city, which is full of chatter and shouts, noisy construction sites and cars clogging the streets and rolling up onto the pavements.

In the north, Serbian, not Albanian, is the language spoken and used for the signs on the shops — fashion boutiques, stationers and everything-for-€1 shops — along the main pedestrianised street. MTS, the Serbian mobile telecoms company that recently won a dispute with the Kosovan authorities over its presence in the country, has a big office by the riverside.

Aside from that, in many ways the north of Mitrovica is not so different from the south. There are the kids clattering about on their tricycles, waiters delivering pizza and beer to outdoor diners, the same skinny stray dogs flopped on the pavement.

Yet at the crossroads at the top of the street, marked by a huge crowned statue of Prince Lazar, a medieval Serbian ruler, there is another stark reminder of the sometimes deadly ethnic tensions in the city. Painted on the walls of the buildings around it are murals, one proclaiming “this country is worth dying for”; another “because there is no turning back from here”. A third has the Russian and Serbian flags intertwined with the words “Kosovo is Serbia — Crimea is Russia” beneath.

A divided city

The bridge over the Ibar in central Mitrovica is guarded by members of Italy’s Multinational Specialised Unit (MSU) – part of the Carabinieri deployed on military missions in Kosovo and elsewhere – and closed off to cars by metal barricades at each end.

Most of the city’s population, around 70,000 people, live on the southern side of the Ibar. Mitrovica was an ethnically mixed city until Yugoslavia started to fall apart at the beginning of the 1990s and the late dictator Slobodan Milosevic brutally repressed Serbia’s Albanian minority. Now the approximately 20,000 Serbs in the north of the city are in the minority, left behind in the new country created when Kosovo declared its independence from Serbia in 2008.

Just over 15 years since then, Serbia still refuses to recognise Kosovo as an independent state, and ethnic unrest has erupted sporadically in Mitrovica since the end of the Kosovan war for independence in 1999. The 2013 Brussels Agreement formalised the separation as North Mitrovica and South Mitrovica became two separate municipalities.

After years of tensions, there was a promising start to 2023 when Belgrade and Pristina came to a new agreement on normalising their relations, following this up with a deal on the implementation of the agreement struck at a summit in Ohrid, North Macedonia in March. However, the agreements were never signed, and since then the situation has deteriorated sharply.

Violence in the north

In May, there were protests in the majority-Serb municipalities of North Mitrovica, Zvecan, Zubin Potok and Leposavic. In Zvecan, the protests erupted into clashes with Kosovan security forces and international peacekeepers in which dozens of people were injured. The trigger for the protests was the installation of ethnic Albanian mayors in the four municipalities. They were elected in votes boycotted — and thus seen as illegitimate — by the Serbs that make up almost all of their populations.

Several mostly later, there was the more serious incident in Banjska village. After killing one Kosovan border guard and injuring his colleague, an armed group forced their way into a local monastery and engaged in an exchange of fire with security forces that resulted in the deaths of three of their number.

Milan Radoicic, the former deputy head of the main party of Kosovo Serbs, the Serb List, was detained by the Serbian police on October 3 in connection with the violence. However, the following day Radoicic — despite having confessed publicly to leading the group — was released from custody.

In Kosovo, Prime Minister Albin Kurti said the police have confirmed that the attack in Banjska was part of a broader plan to annex the north of the country.

“Based on confiscated documentation, the Kosovo Police have confirmed that the terrorist attack was part of a larger plan to annex the north of Kosova via a coordinated attack on 37 distinct positions. Establishing a corridor to Serbia would follow, to enable supply of arms and troops,” Kurti wrote in a post on the X social network (formerly Twitter).

On the southern side of Mitrovica as well as in the capital Pristina, people I spoke to were keen to discuss the events. All were convinced that Belgrade was ultimately behind them, and sceptical of the denials from Radoicic and Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic.

People on the Serb north side, by contrast, were unwilling to talk to bne IntelliNews. However, Serb sources say that ever since Kurti came to power Serbs in the north have become increasingly fearful, and many would like to move to Serbia. Serbs are unhappy that the Kosovan government has not moved ahead with the creation of the promised Association of Serb Municipalities (ASM) in the north of the country, as required under the Brussels agreement.

For their part, Kosovo’s Albanians fear setting up the ASM will lead to the creation of a Serb sub-state within Kosovo, analogous to Bosnia’s Republika Srpska, whose leaders have long threatened to secede and break up Bosnia.

Deadlocked

The failures to progress towards normalisation of their relations is harming both Kosovo and Serbia, by damaging their international reputations and stalling their progress towards EU accession.

Both countries have suffered to some extent, especially since the developments in May, after which the EU announced “punitive measures” against Kosovo over its failure to sufficiently de-escalate the situation in the north. More recently, European Commission spokesman Peter Stano said on October 2 that measures may also be adopted against Serbia, depending on what investigations reveal about the attacks on September 24.

Worries about a new eruption of violence in north Kosovo deepened after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. There were fears that Russia might exploit the existing tensions in northern Kosovo or Bosnia’s Republika Srpska to distract the West’s attention and resources away from the war in Ukraine. Russia is viewed in a positive light in both regions, not least because of its refusal to recognise Kosovo’s independence and its successful efforts to keep Kosovo out of the UN and other international bodies.

One businessman in Pristina told bne IntelliNews that he has repeatedly fielded calls from international clients asking about the security situation. Others reported visitors cancelled trips when they heard about the attack.

“If countries have crises and unfinished conflicts with their neighbours, I think a serious investor wouldn’t invest,” said Ilva Tare, non-resident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Europe Centre, in a recent interview with bne IntelliNews. “Unfortunately the economies suffer because of political and security issues; in the north [of Kosovo] it’s a security issue.”

The other bridge

In Mitrovica, the iconic bridge with its metal arches soaring above the walkways at either side has become a symbol of the divided city (and has been dubbed the ‘journalists’ bridge’ for this reason).

Even as close to Mitrovica as Pristina, a mere 40km away, Mitrovica has the image of a divided, dangerous and unstable city. Yet one local resident says there is frequent back and forth across the Ibar, with people crossing from the north to go to work or shop at the better malls and supermarkets in the south, while Albanians and Serbs do business together.

Indeed, around half a kilometre along the river is another bridge over the Ibar, which unlike the central bridge is not guarded by Carabineri or barricaded off to cars. Instead, cars and pedestrians cross unimpeded from one side to the other.

Back at the central Ibar bridge, on a warm evening in early October a trio of elderly ladies sit chatting on one of the benches on the iconic bridge, while a younger couple watch the setting sun gleam on the water, seemingly unaware of their position at the centre of one of Europe’s potential conflict zones.

Features

Minerals for security: can the US break China’s grip on the DRC?

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is offering the United States significant mining rights in exchange for military support.

Southeast Asia welcomes water festivals, but Myanmar’s celebrations damped by earthquake aftermath

Countries across Southeast Asia kicked off annual water festival celebrations on April 13, but in Myanmar, the holiday spirit was muted as the country continues to recover from a powerful earthquake that struck late last month

India eyes deeper trade ties with trusted economies

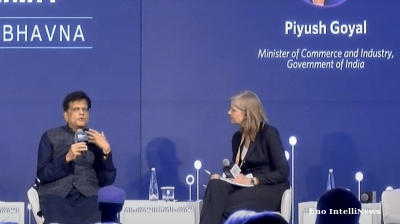

India is poised to significantly reshape the global trade landscape by expanding partnerships with trusted allies such as the US, Indian Commerce and Industry Minister Piyush Goyal said at the Carnegie India Global Technology Summit in New Delhi

PANNIER: Turkmenistan follows the rise and rise of Arkadag’s eldest daughter Oguljahan Atayeva

Rate of ascent appears to make her odds-on for speaker of parliament role.

_1744200906.jpg)