Despite the twin pressures of war and drought, Ukraine’s agricultural sector continues to be a driving force behind the country’s economy, with experts confident of continued growth and investment.

The challenges are significant: according to estimates from Ukraine's Ministry of Agrarian Policy, the gross production of grains and oilseeds in 2024 was around 74mn tonnes, down from 82mn tonnes the previous year.

"Last year we faced a drought. It was quite a severe deficit of moisture. And this negatively affected corn and sunflower production," says Pavlo Martyshev, researcher at the Kyiv School of Economics Agrocentre.

Yet the performance of Ukraine's farms has become increasingly crucial to the country's wider economy during the war. Agricultural goods now account for 60% of the country's exports in 2024, generating almost $25bn in foreign exchange earnings – up significantly from their pre-war level of 40%.

Ukraine's agriculture also remains a cornerstone of global food security. The country frequently ranks as the top global producer and exporter of sunflower oil, and as a top-five exporter of wheat, corn and rapeseed.

While many of Ukraine's major extractive and industrial centres have been occupied or destroyed by Russian aggression, the country's farmland has demonstrated remarkable resilience as a productive force. As Martyshev explains: "Agriculture is relatively more resilient compared to other sectors because it is decentralised. Missiles cannot destroy all the farmland.”

Impact of war

The war has nevertheless had a severe impact on Ukraine’s farms. Around 20% of the country’s farmland cannot be cultivated because it’s occupied by Russian troops or contaminated with landmines.

All along the front line, much of the most fertile land is lying unused by Ukraine’s farmers. Peter Thomson, CEO of Swiss Sustainable Agricultural Holding, has seen a third of his farmland rendered inaccessible.

“Before the war we had 21,000 hectares of land; now we're only operating 13-14,000 ha. We’ve got 6,000 ha of land still occupied in Kherson. There's another almost 1,500 ha of land that we have in Kherson that's been liberated, but we can't operate because it's too close to the front line,” says Thomson.

According to a report by the Institute for Economic Research, it will cost Ukraine over $20bn, or 15% of its pre-war GDP, to repair the damage to its agricultural land, and the process will take ten years. The total income lost by Ukraine’s farmers due to the war stands at $70bn, according to the KSE Institute.

These losses have pushed many of Ukraine’s smaller farms to near bankruptcy. High global grain prices and an abundant harvest in 2020 and 2021 meant that the agricultural sector entered the war with enough reserves to survive the severe disruption unleashed by the war, but this cushion has now been exhausted.

“Now their financial resources are depleted and they need to recover by themselves. And there are problems with financing because banks do not like to lend to small- and medium-sized farms,” says Martyshev.

“The Ukrainian banks are a basket case,” says Thomson, who explains that Ukrainian banks are prohibited from lending to farms that have made losses for two consecutive years. Given the losses suffered by Ukraine’s agricultural sector, this has made it extremely hard for farmers to access the financing they need to buy fertiliser, seeds and equipment.

“We – like an awful lot of other people who lost land and production capacity through occupation or bombing – had two years of losses. Ukrainian banks just say: “okay, we love it, but we can't help you,” says Thomson.

Despite all this, forecasts are optimistic for the future development of the sector: ‘Our projections [predict] an increase in productivity and an increase in the overall profitability of Ukrainian agriculture,” says Martyshev. “Grains and oils production, and also poultry production, will recover relatively rapidly.”

This optimism is reinforced by fundamental global trends that favour agricultural producers, says Thomson: "The amount of people in the world is growing every day. And they're getting wealthier every day as well. They want to eat more and more and more. So the future for farming is good.”

Logistics

Beyond mines and missiles, the biggest challenge for farmers has been getting their produce out of Ukraine. According to Thomson, the main factor affecting the sector’s profitability has been logistical costs, which have fluctuated dramatically based on whether Ukraine's Black Sea ports can safely export grain.

Before the full-scale invasion, most of Ukraine’s grain was exported via the Black Sea. This route was abruptly cut off by a Russian naval blockade following the outbreak of hostilities that sent Ukraine’s exporters scrambling to find alternative routes out of the country.

“The only way we could export from our farms in the south was by road either to the Ukrainian ports on the Danube, or to Romania, which was expensive. It was $80 a tonne extra transport cost. So we lost that amount of money on every tonne that we sold in the first year of the war,” says Thomson.

The Black Sea Grain Initiative brokered by Turkey in July 2022 allowed Ukraine to resume some exports. “It got a little better, but it was still expensive,” says Thomson. Russia pulled out of the grain deal in July 2023, but Ukraine has been able to maintain its maritime exports thanks to a remarkably successful campaign of missile and drone attacks.

By October 2023, Russia’s Black Sea fleet was largely confined to the eastern corner of the Black Sea. Since then, seaborne agricultural exports have almost returned to pre-war levels. “When Ukraine got control of the Black Sea, things more or less got back to where they were before the war,” says Thomson.

Another factor contributing to cheaper logistics is reduced import demand from China, which has brought freight costs down.

“Now China is not importing much corn or soybeans, because of high reserves and an increase in domestic production. And weak Chinese demand [lowers] freight costs. This is beneficial for us, because [for our farmers and exporters to be profitable] they need to have low transportation costs,’ says Martyshev.

Production vs processing

As Ukraine seeks to develop its agricultural sector despite the burdens imposed by war, particular attention is being paid to investment in the processing of agricultural goods.

“Ukraine has significant potential to grow high value-added sectors and move away from the traditional model of agriculture focused on grains and oilseeds,” Ukrainian Agriculture Minister Vitaliy Koval wrote in a recent op-ed for Interfax Ukraine.

Converting Ukraine’s prodigious grain harvests into processed products would help to offset increased transport costs: “the huge opportunity that's left in Ukraine at the moment is deep processing of corn. There's an obvious opportunity to convert Ukraine’s 30mn-tonne corn crop into something that is more valuable, and then the logistic proportion of the cost of a processed good is going to be less than it would be if it was being processed in a factory in Rotterdam or Toulouse,” explains Thomson.

Ukraine has been able to successfully encourage the development of processing in some sectors through protectionist measures, a notable example being sunflower oil; Kernel, Ukraine’s largest agricultural company, is the top sunflower oil-producer in the world, accounting for 8% of global sunflower oil exports. Astarta, another enormous Ukrainian agro-holding, has a highly efficient operation producing sugar from its sugar beet crop.

The immediate prospects for significant investments in processing across different agricultural subsectors are limited, however. “We do not see a large inflow of investments into the processing industry,” says Martyshev. “The demand for processed products is quite low due to high [global] tariffs. Overall, the more processed the commodity is, the higher the import tariff for this commodity is.”

The ongoing war is also limiting appetite for investments in expensive processing plants that are vulnerable to aerial attacks or that could be affected by power cuts, according to Martyshev.

Exports to Europe

The war has, however, made a significant change in the destination of Ukraine’s agricultural produce, most notably through a much greater reliance on exports to Europe. Before the war, Europe accounted for around 30% of Ukraine’s agricultural exports, but this figure has jumped to over 50%, in large part due to the autonomous trade measures (ATMs) introduced by the EU in 2022 that removed tariff restrictions on Ukraine’s agricultural produce.

Whilst this has proved a crucial lifeline to many of Ukraine’s producers, it has also been a rare source of friction between Ukraine and some of its most ardent European supporters. In 2023, Ukrainian grain flooded markets in Poland, causing prices to crash and Polish farmers to mobilise in protest, as bne IntelliNews reported.

Other sectors that have seen huge increases in exports to Europe include Ukraine’s sugar and poultry producers. From a pre-war quota of 20,000 tonnes, Ukraine’s sugar exports to the EU soared to almost 500,000 tonnes in 2023. Ukraine’s poultry exports to the EU surged by 24% to 171,000 tonnes in 2023.

The European Commission imposed a temporary ban on grain imports from Ukraine, and subsequently further amended the tariff-free regime to set limits on imports of certain Ukrainian goods, with sugar, poultry and eggs targeted as a result of pressure from Warsaw and Paris.

The ATM regime is due to expire on June 5, 2025, with negotiations ongoing as to what will replace it, with the possibility that EU-Ukraine trade relations return to their pre-war tariff levels, an outcome that Kyiv is pushing hard to avoid.

According to Oleksandra Avramenko, head of the European Integration Committee at the Ukrainian Agribusiness Club, a return to 2021 conditions would amount to an “economic shock” for Ukraine, with losses in foreign exchange earnings of up to €3.3bn by the end of 2025, a 2.5% hit to Ukraine’s GDP and a reduction in tax revenues of up to 4.15%.

Ukrainian Prime Minister Denys Shmyhal has stated that Kyiv expects the ATM regime to be extended to the end of 2025.

EU membership

Whilst Ukraine’s farms may be a pillar of the country’s economy, they are also a potential sticking point in the country’s EU accession hopes. Ukraine’s wartime experience of negotiating access to the EU market for its agricultural produce may be just a foretaste of the problems to come.

The sheer size of Ukraine's agricultural sector presents challenges for integration into the EU's Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). With 41mn ha of agricultural land – nearly a third of the EU's current farmland – Ukraine's entry would place an enormous burden on the EU’s finances, turning net beneficiaries of the EU budget such as Hungary and Poland into net contributors.

As bne IntelliNews has previously reported, Ukraine’s EU accession is very unlikely in the absence of a reformed CAP.

Whilst the recent experience of European resistance to Ukrainian agricultural imports suggests that competition between European and Ukrainian farmers could be a further obstacle to Ukraine’s inclusion in the European market, Martyshev stresses that EU integration won't necessarily flood European markets with Ukrainian products. "The European market has a surplus in agriculture, and currently the EU primarily purchases products that are deficient, such as corn, sunflower oil and poultry meat," he notes.

Much will depend on the model that is used to bring Ukraine’s agricultural sector into line with EU standards. Whilst EU agricultural production is governed by one of the world's most comprehensive regulatory regimes, Ukraine’s has historically been less stringent, and Ukrainian producers currently follow a regulatory framework that prioritises output efficiency, with lower compliance costs than farmers face in the EU.

While some increased competition between Ukrainian and European producers is expected, Martyshev believes Ukraine's primary markets will continue to be in North Africa and the Middle East. Additionally, meeting EU standards could potentially open doors to Asian markets, where quality standards are currently a barrier to Ukraine’s exports.

The eventual form that Ukraine’s regulatory framework takes will ultimately decide whether Ukrainian produce presents an undercutting threat to European farmers. ”Compliance costs for EU adaptation could be quite high for Ukraine, potentially affecting competitiveness in EU markets," Martyshev cautions. He points to precedents in Eastern European countries such as Hungary and Slovakia, where livestock production declined sharply after EU accession due to costly animal welfare standards – a scenario that could repeat in Ukraine.

EU membership won’t just mean more agricultural goods going from Ukraine to Europe – it might also see farmers coming the other way, says Thomson:

“When Ukraine joins the EU, there will be a huge wave of young Dutch, German, French, British, Danish, Swedish farmers who want to come to Ukraine. They've got their little 500- or 600-ha farms. They've got too much equipment, which they've managed to buy because the CAP over the years has enabled them to overcapitalise their business. And they're looking at their balance sheets and thinking – we could do with another 5,000 ha; let's go to Ukraine."

Features

Minerals for security: can the US break China’s grip on the DRC?

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is offering the United States significant mining rights in exchange for military support.

Southeast Asia welcomes water festivals, but Myanmar’s celebrations damped by earthquake aftermath

Countries across Southeast Asia kicked off annual water festival celebrations on April 13, but in Myanmar, the holiday spirit was muted as the country continues to recover from a powerful earthquake that struck late last month

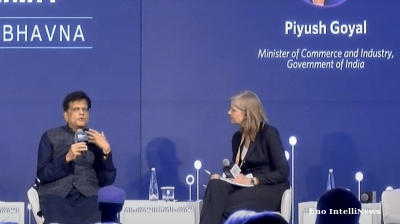

India eyes deeper trade ties with trusted economies

India is poised to significantly reshape the global trade landscape by expanding partnerships with trusted allies such as the US, Indian Commerce and Industry Minister Piyush Goyal said at the Carnegie India Global Technology Summit in New Delhi

PANNIER: Turkmenistan follows the rise and rise of Arkadag’s eldest daughter Oguljahan Atayeva

Rate of ascent appears to make her odds-on for speaker of parliament role.