Handfuls of protesters fight on amid Kazakh parliamentary poll that’s little more than a ritual confirming regime’s power

A handful of protesters stand surrounded by a ring of Special Rapid Response Unit (SOBR) officers on a cold day—the day of Kazakhstan’s parliamentary election on January 10. The polls have long closed—these people have been standing in the wintry cold for eight hours without access to the warmth of heated buildings and no opportunity to even go to a bathroom. Some of the protesters are already experiencing minor frostbite from their prolonged entrapment in the cold—they call for help via social media apps, asking for warm clothes.

The above is a description of the claimed experience of some members of the Oyan Kazakhstan youth movement on election day in Almaty. The group’s Instagram account has attempted to document what it says occurred with multiple posts. Many other activists across the nation were detained by police by the dozens during the day before being released at day’s end.

The most puzzling part of their treatment at the hands of the authorities remains the seeming pointlessness of cracking down on protesters who were relatively few in number and posed no visible threat to the ritualistic parliamentary election organised merely to reaffirm the ruling regime. This point is especially obvious when the January 10 protests are compared to the countrywide rallies seen during the 2019 snap presidential election, a much more substantial manifestation of public anger.

Activists urged citizens to reject all candidates by crossing out their ballot paper.

The question that follows from all of this is whether there was any significance to the seemingly rigged election to speak of?

Power balancing act

Some observers see the election ritual as meaningful as it can reflect the balance of power between the elites and the trajectories of their influence.

Evidence of a power play made by forces aligned with President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev and other players close to Nazarbayev was previously seen in the “breaking of unspoken rules” in Tokayev’s treatment of Nazarbayev’s son-in-law, the oligarch Timur Kulibayev, in 2019. It is also notable that a long time close associate of Nazarbayev, financier Bulat Utemuratov, has been seemingly thrown under the bus as part of the government’s ongoing battle against fugitive banker and self-described dissident Mukhtar Ablyazov.

In May, Nazarbayev’s eldest daughter, Dariga Nazarbayeva, was removed from the position of senate speaker, which placed her as first in line for the presidency in the event of Tokayev being removed from power. The development laid to rest some of the speculation that Dariga was being primed as the “true successor” to Nazarbayev with Tokayev holding a transitory role.

Some observers believe that a close look at the list of members of parliament reflects the level of influence various members of the elite might still have in Kazakhstan. Dariga’s presence on the ballot for the Majilis vote, for example, could be interpreted as a sign of her ongoing, but not necessarily permanent, influence within the elite, despite her aforementioned demotion in May.

As Nur Otan is still controlled by Nazarbayev, it allows the ex-president to continue wielding influence over the balance of power. Moreover, it allows Nazarbayev, who also exercises power via the Security Council, to keep Tokayev in check, an important reality given that many analysts believe that Tokayev’s actions have demonstrated attempts by Tokayev to move away from Nazarbayev. This is at least one perspective on the purpose of the latest Majilis vote.

“In my opinion, Tokayev [is] more interested in a multi-party parliament," Kazakh political analyst at the “Alternativa” think tank, Andrei Chebotarev, told DW in December. Chebotarev added that Nazarbayev would be the “main beneficiary of Nur Otan’s expected victory at the election”.

This idea of a hidden power struggle may be a stretch. After all, Nazarbayev did not seem to offer much support to his old ally Utemuratov.

Tokayev likely still weak

Tokayev is Nazarbayev’s handpicked successor but does not enjoy the free reign over the country that was held by his predecessor. Nazarbayev still largely maintains great influence over the levers of power thanks to his special status as lifetime “Leader of the Nation” and his control of the national security council.

The Majilis vote could mainly be seen to serve as a stress test—whether intentionally or not—of Kazakh citizens’ willingness to challenge the ruling regime like they did in 2019. The results show, however, that the collective will to fight on may have dissipated even if living conditions have deteriorated amid the coronavirus pandemic. That’s striking as inadequate living conditions were a key factor that motivated many during the demonstrations of two years ago.

Features

Indian bank deposits to grow steadily in FY26 amid liquidity boost

Deposit growth at Indian banks is projected to remain adequate in FY2025-26, supported by an improved liquidity environment and regulatory measures that are expected to sustain credit expansion of 11–12%

What Central Asia wants out of the upcoming Washington summit

Clarity on critical minerals and a lot else.

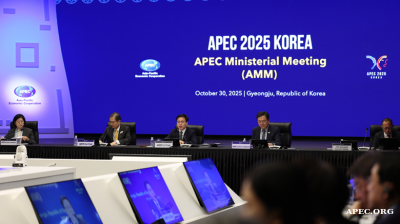

Global leaders gather in Gyeongju to shape APEC cooperation

Global leaders are arriving in Gyeongju, the cultural hub of North Gyeongsang Province, as South Korea hosts the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation summit. Delegates from 21 member economies are expected to discuss trade, technology and security.

Project Matador marks new South Korea-US nuclear collaboration

Fermi America, a private energy developer in the United States, is moving ahead with what could become one of the most significant privately financed clean energy projects globally.