Total Czech beer exports are continuing to decline, according to data from the Czech Association of Brewers. Czech beer exports dropped by 4.3% in 2023 to 5.7mn hectolitres, pulling the total down to near the levels of 2018 and outpacing the decline in domestic beer consumption.

This comes as the global beer market is largely stagnant, with consumption growing slowly but still expected to remain under pre COVID-19 levels through 2027, according to Statista data.

Yet despite the export decrease, more than one out of every four beers brewed in the country were still shipped abroad, making beer exports an essential market for Czech brewers of all sizes. This proportion outstrips Germany’s 17%, but is still behind the levels of The Netherlands (55%) or Belgium (70%). The exports still primarily go to neighbouring countries, with EU countries taking in about 75% of the total.

Liquid history

Czech beer exports are certainly not new, with the first recorded transactions taking place in the Middle Ages. More recently, Plzeňský Prazdroj’s first exports were in 1856 – just 14 years after the Plzen brewer came up with its renowned clear golden lager.

Bohemia as a cradle of beer culture region has given the world the famous Saaz hops, one of the first schools for brewing, and, of course the pilsner type of beer.

For decades, the export leaders were Plzeňský Prazdroj (now part of the Japanese Asahi) and the state-owned Budvar, located in Ceske Budejovice (Budweiser in German).

After the collapse of communism, when privatisation in the 1990s opened the doors to foreign investment, the Czech brewing sector also came into the sights of multinational brewers.

They were drawn to Czechia partly because local beer consumption topped the world charts with its per capita consumption, but mainly because of the international name recognition of Czech beers, with analysts citing the precedent of Heineken, which ships beer across the Atlantic, as what could potentially happen to Czech beer.

The British Bass group went for Staropramen, developing the British market for licensed Staropramen. Heineken picked up Krusovice and a handful of local brewers, while South African Brewers (SAB) got the big prize, acquiring Plzeňský Prazdroj and its near half of the total market.

SAB, with their ‘Golden Thread” strategy, aimed to use Pilsner Urquell as their global flagship brand. They knew their African Castle lager was not up for the task – because it lacked the history and image a premium brand demanded.

However, the need for a Czech flagship changed when Asahi took over Plzeňský Prazdroj, as the Japanese brewer already had its own flagship brew. Asahi now has five “hero” brands listed on its website – and they include Pilsner Urquell and Kozel – the first brewed only in the Czech Republic and the second brewed both in the Czech Republic and abroad.

Overall, Czech exports have almost tripled in the 25 years since SAB entered the market. In 1998, exports were 1.8mn hectolitres and Budvar was the leader. By 2019 exports had peaked at 5.3mn hectolitres, and Plzeňský Prazdroj is now the leading exporter.

Deep dive into exports

Last year’s 4.3% drop in exports was not spread evenly between brewers. A look at several leading brewers – Heineken, Plzeňský Prazdroj and Budvar – showed that each are taking a different path to market. A closer look at the data shows that most of the drop is due to changes at just one international brewer – not changing tastes abroad.

Heineken was the big loser when it came to Czech exports, dropping volume by over half. The loss of 265,000 hectolitres knocked the brewer down from fourth to fifth position among Czech exporters. Despite this drop, Heineken’s domestic sales were virtually unchanged, dropping a slight 1.13%. Heineken with its three breweries is still the third largest brewing group in the Czech Republic by volume.

Heineken has not commented on the change. Two theories are that the lost volume came from the Russian market, or the global company simply made a change in its European export portfolio.

On an international level, Heineken came under fire for its slow and inconsistent stepping away from their Russian operations in 2023. Yet data from the Czech Brewers shows that most of the total drop in exports was from direct shipments to EU countries, not those in the “Non-EU” category.

Plzeňský finds the price limits

Plzeňský Prazdroj is the dominant player on the local market – and also the number one export group. Its flagship Pilsner Urquell is the unquestioned Czech “A” brand. But when it comes to exports, the Czech brewers association data shows a volume drop of 7.25% and the company’s own press release a tiny dip of 0.6%.

That’s the difference between real and virtual exports. Both figures are correct because the Association data shows only physical beer exports and Prazdroj’s data also includes 3.3mn hectolitres of licensed production brewed outside the country. While the flagship Pilsner Urquell is brewed only in the Plzen brewery for export, their more mainstream Kozel brand has been used for licensed production. These virtual exports lead actual exports by nearly a 2 to 1 ratio.

While at home Plzeňský Prazdroj is the unquestioned price leader, it has a more competitive market abroad. This has led to reports of Pilsner Urquell being sold for less abroad than at home.

It’s a question of market power and positioning, points out Tomas Maier, economics professor at the Czech University of Life Sciences in Prague. “Plzeňský Prazdroj sells products in Czechia with a higher price, because in Czechia they are the price leader. In Germany, their brands are not important brands, so in Germany the Pilsner Urquell and Kozel brands are cheaper.”

Budvar continues to grow

Best known for its unending court cases over the Budweiser name against the US giant Anheuser-Busch, Budvar cemented its position as the country’s second largest beer exporter – and continues to shore up its local position. The state-owned Budvar made solid gains on the export and local markets, with growth of 4.6% and 3.8% respectively.

Budvar is an unusual company in that it has a nationalistic brand image, is state-owned, managed via the Czech Ministry of Agriculture, and still sells a phenomenal 72% of its brew abroad. The top four export destinations for Budvar are Germany, Poland, Slovakia and the UK.

In addition to its David versus Goliath positioning against the American Budweiser, Budvar has also worked on its craft beer image at home and abroad. With its Partnership Brewing project, it has worked with craft brewers in Great Britain, Germany and Denmark on variations of the “Czech lager” category.

Does beer still need a home?

In the decades since privatisation, the global position of imported products – whether beer or BWM cars – has shifted. Consumers are increasingly happy with brands that are no longer manufactured at just one place on the map. Czech brewers, on the other hand, do like that geographic link, even if multinational brewers downplay it. “Every beer needs a home,” was a favourite statement by former Budvar CEO Jiri Bocek.

Budvar has long trumpeted its local origins in the fight for the Budweiser name. This also means that production is tied to local ingredients such as water, malt and hops. They have also positioned themselves as the special champions of the Czech beer style among craft brewers.

Plzeňský Prazdroj has threaded the needle both ways with its premium Pilsner Urquell that is brewed only in Plzen. More recently, it and its parent Asahi have promoted Czech hops with the ProChmel irrigation project. However, volume brands such as Kozel can be brewed abroad.

But, it’s not just Budvar or Prazdroj with a local label. Czech brewers have fought to make geography part of the branding. From 2008, they’ve had the right to put a Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) marker and the “Cesky Pivo” moniker on brews with local ingredients.

Czech beer exports have a future, according to Tomas Maier: “Czech beer means something with high quality, so it is still an excellent export article.”

Features

Minerals for security: can the US break China’s grip on the DRC?

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is offering the United States significant mining rights in exchange for military support.

Southeast Asia welcomes water festivals, but Myanmar’s celebrations damped by earthquake aftermath

Countries across Southeast Asia kicked off annual water festival celebrations on April 13, but in Myanmar, the holiday spirit was muted as the country continues to recover from a powerful earthquake that struck late last month

India eyes deeper trade ties with trusted economies

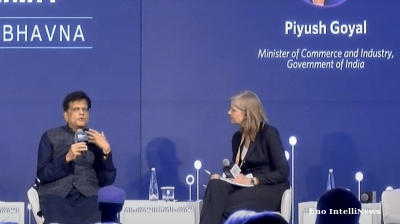

India is poised to significantly reshape the global trade landscape by expanding partnerships with trusted allies such as the US, Indian Commerce and Industry Minister Piyush Goyal said at the Carnegie India Global Technology Summit in New Delhi

PANNIER: Turkmenistan follows the rise and rise of Arkadag’s eldest daughter Oguljahan Atayeva

Rate of ascent appears to make her odds-on for speaker of parliament role.