It’s not only Russian oil and gas that the European Union is working to shun as the bloc attempts to break free of its energy links with the Kremlin. Some essential efforts, for instance, are directed at ending European member states’ nuclear power use of Russian uranium.

Attention turns to Kazakhstan. As of today, Kazakhstan provides more than 41% of the world's uranium supplies, followed by Australia (13%) and Canada (8%). And the Kazakhs boast huge, unexploited uranium resources that could drive up that already major market share. Surely Kazakhstan is the answer? Unfortunately for the EU, things are not so simple.

The reality is that uranium mining is only one facet of the nuclear energy production process. Unprocessed uranium ore cannot be used as nuclear reactor fuel. The ore must be refined to produce a concentrate of the heavy metal, or yellowcake, then converted into uranium hexafluoride gas. This is where Russia shines.

Data up to 2020, shows that only four uranium converter facilities for the production of uranium hexafluoride gas—with one each in Russia, China, France, and Canada—were in commercial operation. In fact, Russia boasts around 40% of the world's uranium conversion infrastructure and provides the global market with around one-third of utilised uranium hexafluoride gas.

The conversion, of course, is indispensable. Only after conversion, can enrichment and the making of nuclear fuel take place.

In 2020, EU utilities bought around 20% of their uranium and 26% of their uranium enrichment services from Russia, while the US percentages (taken from 2021 data) were roughly 14% and 28%, respectively. Replacing such supplies will be no mean feat, but the objective is entirely reachable, and desirable, given how warring Russia, for Europe, no longer has the credentials of a reliable energy supplier.

In the US, there is an emphasis on putting in place urgent funding and efforts to exploit and enrich far more domestic uranium resources, but, given its proximity to Europe, EU eyes are very much fixed on Kazakhstan in the effort at excluding Russia from the nuclear fuel making process.

“We simply cannot rely on a supplier who explicitly threatens us,” European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen said in March, following the late February Russian invasion of Ukraine.

In all, 15 nations meet 75% of the world's uranium demand, with Kazakhstan the leading exporter since 2009, according to the World Nuclear Association. What’s more, Kazakhstan is blessed with large uranium resources close to the surface that can be harvested at low cost by injecting fluids beneath the earth in a method akin to hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking”.

But the European plans to boycott Russian uranium and Russian uranium conversion services face further problems.

Even though Kazakhstan is the world’s biggest player in uranium supply, much of its milled uranium travels through Russian conversion plants before it is exported to global markets.

Still, if the multiple transportation, logistical conversion and—not to forget—political obstacles can be overcome, Kazakhstan, given its uranium riches, would be in the ideal situation to become Europe’s pre-eminent and reliable uranium supplier for decades to come. And that brings us to Kazatomprom.

Largest, low-cost producer

In Kazakhstan, Kazatomprom JSC controls all uranium exploration, mining and other nuclear-related activities, including nuclear material import and export.

As the National Atomic Company of Kazakhstan, Kazatomprom benefits from priority access to all uranium deposits in Kazakhstan, the largest, low-cost uranium producing country in the world.

A nuclear fuel assembly (Credit: Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission, France (public domain)).

Kazatomprom assets include the entire complex of enterprises in the country involved in the front-end of the nuclear fuel cycle, from geological exploration, through to uranium mining the and nuclear fuel production cycle, through to scientific research and the development of patented technologies.

The extensive asset portfolio also comprises of 14 uranium mining assets across 26 deposits in Kazakhstan. The company, it seems, also has the ability to significantly grow its resource base with relatively little capital investment.

The uranium producer stated in its mid-year financial statement that it has the confidence to target 2024 uranium output that will be 2000–3000 tU (tonnes of elemental uranium) over the anticipated 2023 level, thanks to mid-term and long-term contracts.

”Kazatomprom expects to fully participate in the mid- and long-term contracting cycle associated with the anticipated demand growth for nuclear fuel, backed by our now-proven commitment to building long-term value for our stakeholders through continued production and sales discipline,” said Yerzhan Mukanov, Kazatomprom’s chief operations officer and acting CEO.

The main route for exporting Kazakhstan's uranium remains via St Petersburg, Russia. The corporation has plans to use an alternative route that avoids Russian territory and take consignments across the Caspian Sea at least once in the remainder of this year, even though, according to Kazatomprom chief commercial officer Askar Batyrbayev, the St Petersburg option has remained uninterrupted despite economic disruption and uncertainties caused by consequences of the war in Ukraine.

The cost of shipping Kazatomprom product via the Caspian Sea option will be "somewhat higher", Batyrbayev conceded, but added: "I guess we'll be using the Caspian route a little more frequently than we did before."

The wisdom of having alternative export routes to those that run through Russia has been demonstrated this year by major difficulties Kazakhstan has encountered getting crude oil to world markets via its main oil export route, the CPC pipeline that runs to the Russian port of Novorossijsk on the Black Sea—there are suspicions that the Russians, looking to manipulate the markets and show Kazakhstan who’s boss, have been making up excuses to deny Kazakh oil unhindered entry to the export terminus at the port.

Kazatomprom has forged major strategic links with Japan and China as well as Russia. It once held a significant stake in international rival Westinghouse, but sold it in 2017. Canada's Cameco and France's Orano are, meanwhile, involved in Kazatomprom's fuel cycle, uranium mining and other activities.

A competitive advantage of Kazatomprom stems from its exclusive use of the in-situ recovery (ISR) mining method, also called in-situ leaching (ISL). In ISR, minerals such as copper and uranium are recovered through boreholes drilled into a deposit, in situ. In situ leaching works by artificially dissolving minerals occurring naturally in a solid state.

ISR is said to offer an unmatched structural cost advantage, production flexibility and inherent environmental and safety benefits.

The company is also supported by a sales structure that is situated close to the nuclear electricity markets that have the highest growth rates in the world.

The international discussion surrounding the greater need for energy security not linked to unpredictable regimes has been a key factor contributing to the improved uranium market conditions seen of late. There is now a bullish outlook for the nuclear power sector.

Several countries, including some that had given up on nuclear plans or were dedicated to phasing out nuclear energy, are re-evaluating nuclear in tandem with their renewable energy strategy. Kazakhstan itself is pushing forward with a Project to have its first nuclear power station up and running within around 10 years.

‘Obama-Nazarbayev fuel bank’

Any nuclear industry representative headed for Oskemen in East Kazakhstan might be on their way to Kazatomprom’s Ulba Metallurgical Plant or perhaps to the International Atomic Energy Agency Low-Enriched Uranium Fuel Bank located at the plant.

IAEA Low-Enriched Uranium Fuel Bank, at Kazatomprom's Ulba Metallurgical Plant in Oskemen, East Kazakhstan (Credit: NAC Kazatomprom JSC, cc-by-sa 4.0).

The fuel bank was established in 2017 after close cooperation between the then US Obama administration and the then Kazakh presidency of Nursultan Nazarbayev. It serves a global initiative to maintain a secured supply of nuclear fuel for International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) member governments that would be available in the event of disruption to standard supplies of low-enriched uranium (LEU).

A nation devoid of nuclear weapons (the US spent towards a quarter of a billion dollars helping Kazakhstan eliminate its weapons of mass destruction and related infrastructure after the fall of the Soviet Union), accessible to IAEA inspectors, was sought for the fuel bank. It has the capacity to provide 90 tonnes of LEU for the production of nuclear fuel assemblies.

Officials say Kazakhstan holds itself to high standards when it comes to making the most of the chances offered by peaceful nuclear energy to establish a new high-tech industry, dominate the world market for nuclear fuel, and advance its own internal scientific and technological capacity. That’s why Astana wishes to boost cooperation in this area with nations that possess cutting-edge nuclear cycle technologies and practical experience with those.

The successful realisation of the fuel bank project goes down as an international marketing “win” for Kazakhstan when it comes to establishing nuclear investment and political alliances that will potentially allow the country to upgrade its role as a supplier of raw materials to the world's atomic energy industry, while also sourcing top technologies for expansions into nuclear power production and uranium refining.

Russia has long used its nuclear power prowess in cementing ties with fellow emerging markets that have no nuclear power tradition of their own. Moscow’s ambitions to sell nuclear power technology and nuclear plant building to most of Europe appear mostly over, however, given the ruptures caused by its decision to go to war in Ukraine (though there are exceptions where Russian nuclear suppliers are still welcome in Europe, such as Hungary), but Russia still has plenty of potential clients looking east and south.

In recent years, Russia’s Rosatom has completed the construction of six nuclear power reactors in India, Iran and China. It has nine reactors under construction in Turkey, Belarus, India, Bangladesh and China. The company also confirmed to bne IntelliNews that it has 19 more “firmly planned” nuclear projects and an additional 14 “proposed” projects, almost all of which are in emerging markets. One project is known to be in Uzbekistan. Since the start of the Ukraine war there have been some rumours that the Uzbek investment might not happen, though Tashkent has denied any such decision has been made.

Like gas pipelines, nuclear power stations offer Russia a way of binding countries to economic and, to varying extents, geopolitical relationships. Whether Russia goes on to play a main or key role in constructing Kazakhstan’s first nuclear power plant will say a lot about the post-Ukraine war shape of Moscow’s relationship with Central Asia’s largest economy. Nuclear power stations can come with 60-year-long maintenance deals and uranium supply contracts. One does not enter into such deals lightly.

Russia has long used energy as the sweetener in generating trade arrangements with export markets. Where uranium is concerned, much of what it achieved has gone sour. No-one can blame Kazakhstan for sensing opportunities.

Features

Minerals for security: can the US break China’s grip on the DRC?

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is offering the United States significant mining rights in exchange for military support.

Southeast Asia welcomes water festivals, but Myanmar’s celebrations damped by earthquake aftermath

Countries across Southeast Asia kicked off annual water festival celebrations on April 13, but in Myanmar, the holiday spirit was muted as the country continues to recover from a powerful earthquake that struck late last month

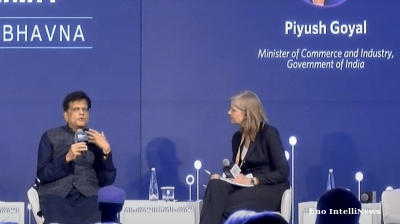

India eyes deeper trade ties with trusted economies

India is poised to significantly reshape the global trade landscape by expanding partnerships with trusted allies such as the US, Indian Commerce and Industry Minister Piyush Goyal said at the Carnegie India Global Technology Summit in New Delhi

PANNIER: Turkmenistan follows the rise and rise of Arkadag’s eldest daughter Oguljahan Atayeva

Rate of ascent appears to make her odds-on for speaker of parliament role.

_1744669887.png)