Russia’s oil and gas revenues surged in the first three months of this year by 79%, but Reuters calculated they will double in April compared to the same month a year earlier, the newswire reported on April 24.

Reuters calculates Russia’s total revenue at RUB1.292 trillion ($14bn), up from RUB648bn ($7bn) in April 2023. That is slightly down from the RUB1.308 trillion ($14.1bn) generated in March.

The results of the first three months saw Russia’s budget deficit halved, affected a poor result in February. Russia's budget deficit fell from RUB1.5 trillion in February against the full-year forecast of RUB1.6 trillion, but narrowed to RUB607bn for the first three months of the year, or 0.3% of gross domestic product (GDP), supported by a surge in oil prices. Oil and gas revenues in the first three months of this year surged 79% year on year and make up about a third of Russia’s tax take.

Ministry of Finance (MinFin)’s forecast for the full 2024 deficit is also half last year’s deficit of 2023 of RUB3.2 trillion, or 1.9% of GDP.

For 2024 as a whole, the government has budgeted for federal revenue of RUB11.5 trillion from oil and gas sales, up 30% from 2023 and reversing that year's 24% decline owing to weaker oil prices and sanctions-hit gas exports.

|

Russian budget RUB bn |

|||

|

3M24 |

3M23 |

Change% y/y |

|

|

Revenues |

8,719 |

5,679 |

53.5 |

|

Oil & gas rev |

2,928 |

1,635 |

79.1 |

|

Non-oil & gas |

5,791 |

4,044 |

43.3 |

|

VAT |

3,356 |

2,693 |

24.6 |

|

Expenditures |

9,326 |

7,765 |

20.1 |

|

Deficit cash |

-607 |

-2,086 |

|

|

Deficit%GDP |

0.3 |

-1.2 |

|

|

source: MinFin |

|||

Reuters' calculations are based on data from industry sources and official statistics on oil and gas production, refining and supplies on domestic and international markets.

As bne IntelliNews reported, one year on from Russia’s disastrous start to 2023, the Russian budget has improved remarkably.

Reuters’ upbeat assessment is partly due to a low base effect, after oil and gas revenues fell by 49% y/y in January last year as the twin oil and oil product sanctions came into force on December 5, 2022 and February 5, 2023 respectively.

At the same time, Russia posted a very large RUB3.2 trillion deficit at the end of 2022 after 11 months of surpluses, and started 2023 with a record breaking RUB1.7 trillion deficit in January 2023 – almost the entire allotment for the full year – and actually exceeded the full-year deficit forecast in March 2023.

However, the situation rapidly reversed last spring and all those results recovered as the year wore on. The MinFin tinkered with the tax system to take account of the new realities and oil tax dollars began to flow again in around March. Oil revenues recovered completely in the second half of the year. (chart)

By December 2023, the budget was on course to come in under 1% of GDP when many analysts were predicting it would finished 2023 at 3-6% of GDP. However, traditional heavy spending in December saw the final full-year deficit of 1.9% of GDP, or RUB3.4 trillion. December usually accounts for a fifth of all spending in that month alone, as the chart shows.

The modest cumulative deficit percentage in 2023 was helped by the unexpected strong economic growth of 3.6% for the full year after the economy got a Keynesian boost from the heavy state military spending.

This year that strong economic growth is expected to continue. The Central Bank of Russia (CBR) forecasting a modest 2.2% growth in 2024 in its April macroeconomic survey, but the International Monetary Fund (IMF) just upgraded its Russian economic outlook from 1.1% to 3.2% in 2024, making Russia the fastest growing large economy in the world this year. And Russian Finance Minister Anton Siluanov also increased his growth forecast to 3.6% – the same as last year.

The military Keynesian effect appears to be very strong. And it is being helped by a growing consumer boom. As the table shows, while most commentators focus on Russia’s dependency on oil and gas revenues, they only account for about a third of the tax take. The other two thirds is from non-oil and gas revenues, which was up a healthy 43% in the first three months of this year. More than half of the non-oil revenues are from VAT, which was up by nearly a quarter.

Inflation is running high at 7.7% in March, which has forced the CBR to hike the prime rate to a crushing 16%. But the acute labour shortage caused by the war sent nominal wages up by 14.1% in 2023 and they are predicted to increase by 10.4% this year, while inflation is anticipated to fall to 5.2%, according to the CBR’s survey. That means real wage growth in Russia are growing strongly and fuelling a consumer boom. Real wages were up a whopping 7.8% last year, despite the high inflation, and the CBR says they will climb by at least 3.2% this year.

All that consumption is driving the healthy VAT collections that may end the year some three times higher than oil and gas receipts, according to MinFin’s budget assumptions for this year.

After the imposition of extreme sanctions at the start of the war in Ukraine, economist cut their estimates of Russia’s growth potential from 1%-1.5% pre-war to 0.3%-0.5%. However, thanks to the supercharging of the economy as the Kremlin switches tactics from hoarding money to build up $600bn of CBR reserves and is now spending freely with heavy investments to militarise the economy, some economists now estimate Russia’s economic growth potential has risen to 3.5%.

German Defence Minister Boris Pistorius said that Russia is already producing more weapons and ammunition than it needs for conducting an aggressive war against Ukraine on April 25.

With the increased spending on armaments and the streamlining of the military economy, "a significant portion or part of what is produced no longer goes to the front line, but ends up in warehouses".

Siluanov estimates that the budget deficit will fall from last year’s 1.9% of GDP to 0.8% this year and that the budget will be balanced in 2025 – and this assuming the war is still going on.

Putinomics

The Kremlin has fundamentally changed its economic strategy. Since Russian President Vladimir Putin began to rearm and modernise the military in around 2012, as bne IntelliNews reported in a cover story Cold War II at the time, Russia has been hoarding money to make itself sanctions proof and has built a Fiscal Fortress.

At the same time, Russia has been reducing its external debt to the point where debt it can pay off almost its entire debt worth 14% of GDP tomorrow in cash. (chart)

However, the big change is that the Kremlin has started to leverage its economy for the first time since Putin took over by increasing its borrowing from the domestic markets, albeit still conservatively.

The two core principles of “Putinomics” have been: build up massive reserves that topped $600bn pre-war, or nearly two years’ worth of import cover, where most economists say three months is sufficient; and keep debt ridiculously low, in the low teens at most.

Most Western economies have debt-to-GDP ratios well over the 60% “safe level” set by the Maastricht treaty – the US debt is now over 123% and has started to worry the IMF, according to comments made at the most recent spring meeting.

All that changed dramatically after the war started. Russia began to run budget deficits for the first time in two decades and to spend heavily. Increasingly, funding the state’s fixed investment is from issuing Russian Finance Ministry’s OFZ treasury bills bonds to “friendly investors” or tapping the giant RUB19 trillion pool of liquidity in the domestic banking sector.

In December Siluanov announced a dramatic scaling up of borrowing plans in 2024 to raise RUB4.1 trillion from domestic borrowing – more than last year and a bit less than double the pre-war level of domestic borrowing – and the outstanding volume of OFZ has been growing steadily to the current circa RUB20 trillion outstanding. (chart)

Sanctions failing

Putinomics appears to be working as Russia’s economy looks increasingly robust. The Reuters’ forecast show that the Kremlin is successfully undermining Western sanctions targeting Moscow's oil and gas industries.

As bne IntelliNews has reported, oil sanctions are largely a spent cannon and the technology sanctions have also largely failed, as Russia has imported more equipment and electronics in 2023 than it did pre-war. However, the US has made some progress since December with its new regime of smart sanctions that have driven “friendly” banks from China, Turkey and other countries from the market, have selectively targeted very specialised equipment in things like the LNG sector, and the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) has effectively removed over 40 oil tankers from Russia’s shadow fleet with the threat of secondary sanctions.

Western leaders are looking at ways to restrict how much money the Kremlin can generate, much of which goes towards funding Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

The EU intends to crack down on Russia’s shadow fleet in the upcoming fourteenth sanctions package. EU Trade Commissioner Valdis Dombrovskis said earlier in April that the 14th round of sanctions against Russia should be adopted in the spring.

G7 countries are struggling to reverse this success. After two years and the increasingly obvious failure of sanctions to restrict the Russian economy, the emphasis has gone from targeting products with flawed sanctions due to the exemptions and calve-out ridders in order to shield EU companies, in particular that remain dependent on these supplies, to tightening the rules to make the existing sanctions more effective.

Not a single barrel of Russian crude oil has been sold below the oil price cap of $60 since that sanction was imposed at the start of 2023, but the more recent smart sanctions seem to be having more of an effect.

“We need to tighten the regime and force the Russian oil trade back inside the regulated regime,” says Benjamin Hilgenstock, a senior economist with the Kyiv School of Economics (KSE).

The European bloc has already adopted 13 packages in response to Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, aiming to undermine Moscow's economic output and the ability to sustain the war. Earlier this month, EU Executive Vice President Valdis Dombrovskis said that a fourteenth sanctions package is in the works and will likely include measures aimed at Russia's sanctions circumvention, and pay special attention to the targeting the shadow fleet.

Features

Minerals for security: can the US break China’s grip on the DRC?

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is offering the United States significant mining rights in exchange for military support.

Southeast Asia welcomes water festivals, but Myanmar’s celebrations damped by earthquake aftermath

Countries across Southeast Asia kicked off annual water festival celebrations on April 13, but in Myanmar, the holiday spirit was muted as the country continues to recover from a powerful earthquake that struck late last month

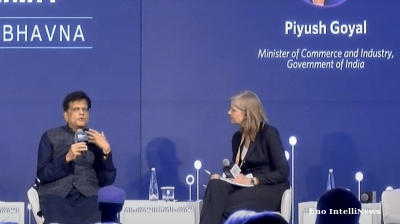

India eyes deeper trade ties with trusted economies

India is poised to significantly reshape the global trade landscape by expanding partnerships with trusted allies such as the US, Indian Commerce and Industry Minister Piyush Goyal said at the Carnegie India Global Technology Summit in New Delhi

Farm to front line: Ukraine's wartime agriculture sector

Despite the twin pressures of war and drought, Ukraine’s agricultural sector continues to be a driving force behind the country’s economy, with experts confident of continued growth and investment.

_1744669887.png)