Russia’s oil and gas reserves will last for another 59 and 103 years respectively, says natural resources minister

There has been some talk of Russia having passed “peak oil” in the last two years after output fell from an all-time high of 11.2mn barrels per day to 10.4mn bpd in April thanks to the OPEC+ production cuts deal. Experts say that for technical reasons some of the oilfields that have been idled will not be easy to bring back into production and might have to be written off.

Not so, says Russia’s Natural Resources Minister Alexander Kozlov, who claimed last week that Russia has enough extractable oil still in the ground to maintain production for another 59 years and gas reserves that can be exploited for another 103 years.

“Availability of all oil reserves with existing production stands at 59 years given the current production level, and for natural gas it is 103 years,” Kozlov said as cited by RBC on May 11. “But we understand that this is only a general balance. There are fields that are being unlocked, while there are fields that are yet to reach full load. Anyway, we have to improve geological exploration, including exploration in remote areas. We have the goal of loading the Northern Sea Route [NSR], hydrocarbons will become its basis.”

Most of Russia’s oil production is concentrated, and has been since Soviet times, in west Siberia, but east Siberia, that has a very similar geography and is believe to hold significant unexploited reserves, remains underdeveloped.

More recently Russia has also begun to explore and exploit the Arctic region that is also thought to hold even more reserves and is becoming increasingly accessible thanks to the ice melt due to global warming.

Russia is also developing the so-called NSR, a shipping channel across the top of Russia that significantly shortens the transport links between Europe with Asia and is building a fleet of nuclear powered icebreakers to traverse it.

However, there are still restrictions on accessing this oil and gas. While the pipeline infrastructure in Western Siberia is well developed that in Eastern Siberia and the Arctic still needs to be built. Exploiting the fields has also been made more difficult by US sanctions on advanced oil extraction technology exports to Russia where equivalent technology does not exist.

And the global warming that is making more fields accessible is also threatening the existing pipeline network as Russia’s permafrost is melting, which could see the existing pipelines sink into a quagmire if the year-round rock-hard ground turns into mud.

“It will be difficult to maintain production costs of hard-to-recover oil,” Kozlov said. “The price of the end product exerts pressure on the industry, while the foreign partners do not allow the Russian oil industry to use some technologies. Still, the government helps the companies by taking on some costs, including the cost of geological exploration, so that the companies spend more on production.”

Kozlov’s estimates are an upgrade from previous estimates that put the reserves of oil at closer to 57 years, according to Kozlov’s predecessor Sergey Donskoy in a 2017 estimate. The expanded gas estimates are based on exploration of the Arctic region, which contains 72% of the country’s natural gas deposits and 25% of its oil.

Kozlov conceded that more geological surveys are needed to firm up the estimates, particularly in more remote areas.

Features

Southeast Asia welcomes water festivals, but Myanmar’s celebrations damped by earthquake aftermath

Countries across Southeast Asia kicked off annual water festival celebrations on April 13, but in Myanmar, the holiday spirit was muted as the country continues to recover from a powerful earthquake that struck late last month

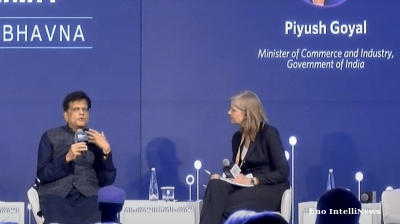

India eyes deeper trade ties with trusted economies

India is poised to significantly reshape the global trade landscape by expanding partnerships with trusted allies such as the US, Indian Commerce and Industry Minister Piyush Goyal said at the Carnegie India Global Technology Summit in New Delhi

Farm to front line: Ukraine's wartime agriculture sector

Despite the twin pressures of war and drought, Ukraine’s agricultural sector continues to be a driving force behind the country’s economy, with experts confident of continued growth and investment.

Western Balkans countries struggle to reverse demographic decline

Governments turn to short-term fixes and immigration push to tackle deepening demographic crisis but shy away from deeper reforms, says OSW report.