In the more than 30 years that the Central Asian states have been independent there have dozens of crackdowns on perceived opponents of their governments, but none reached the level of the repression the Tajik administration is currently meting out to the Pamiri peoples of the eastern Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast (GBAO).

Most of the influential local figures in GBAO have been either arrested or killed since mid-May when government forces initiated a so-called anti-terrorism operation in response to peaceful protests in the regional capital Khorog.

And the crackdown is continuing.

GBAO is different from the rest of Tajikistan and that is the reason for the unprecedented repressive campaign still underway there.

The region accounts for more than 40% of the territory of Tajikistan, but nearly all of it is mountainous, with some peaks reaching altitudes of more than 7,000 metres. Of the 10mn citizens of Tajikistan, only around 250,000 live in GBAO and most of them are Pamiris who are ethnically, culturally and linguistically distinct from Tajiks.

Most Tajiks are Sunni Muslims, but Pamiris are Shiites of the Ismaili sect, followers of the Aga Khan, the 49th imam in the unbroken line that started with Ali.

The territory of modern-day GBAO has always been a remote area. Before the arrival of Russians at the end of the 19th century, few outsiders ever made their way into the mountain fastness of the region. People have been living there for thousands of years. The ruins of the Yamchun and Khakha fortresses in GBAO date back to the 3rd century BC.

Only one road connects GBAO with the Tajik capital Dushanbe and that road is often closed by snow and avalanches. There is a small airport at Khorog, but unpredictable mountain weather often prevents planes from travelling there for weeks at a time.

Tajik President Emomali Rahmon (Credit: Indian Prime Minister's Office (GODL-India)).

Tajik President Emomali Rahmon, in power since 1992, has gradually consolidated his grip over Tajikistan in the years since the 1992-1997 Tajik civil war, but Tajik authorities have only ever had a tenuous hold over GBAO and that was only possible by working with influential local figures, who came to be known as “informal leaders”.

The protests that happened in May could not happen anywhere else in Tajikistan. The government has been firmly in control of the rest of Tajikistan for years and any attempt at a public demonstration of dissatisfaction is quickly neutralised.

Khorog on May 16 (Credit: Screengrab).

But in GBAO protests have happened several times since the end of the civil war and the violence in May, while the worst seen since the days of the confict, was not the first incident of unrest in the 25 years since the Tajik peace accord was signed.

Most of GBAO was opposition territory during the civil war. The Pamiri group Lali Badakhshan, the Ruby of Badakhshan, was part of an interesting coalition of Islamic and democratic groups that formed the United Tajik Opposition (UTO) and fought against government forces. The rugged terrain of GBAO made the region ideal for UTO bases.

Rahmon’s government has never forgotten the role that GBAO and its people played during the civil war.

The Aga Khan Foundation plays a big role in development for the Pamiri people, who are ethnically, culturally and linguistically distinct from Tajiks (Credit: AmanovDmitry, cc-by-sa 3.0).

But unemployment remains high in GBAO, something which has fuelled the illegal trafficking of many items, from narcotics to precious and semi-precious stones.

Tensions became high in GBAO from November 25, 2021, when 29-year-old GBAO resident Gulbuddin Ziyobekov was killed by security forces. Months earlier Ziyobekov had beaten and humiliated a local security official who had lecherous designs on a local woman. Police said Ziyobekov offered armed resistance in November when they came to detain him, but many in the Khorog area thought Ziyobekov was hunted down and murdered.

Ziyobekov’s body was brought to the Khorog administration building and a protest involving several thousand people started. There was also a protest outside the Tajik Embassy in Moscow and briefly a small protest outside the UN office in Dushanbe.

Two more people were killed in Khorog before the protest ended. The internet connection to the region was cut and remained so until late March when it was partially restored.

Government officials negotiated with local leaders, as they had done several times in the past, and a truce was reached, and the government promised to investigate the causes of the violence.

Local activists formed a group called Commission 44 to work with state investigators, but by January, members of Commission 44 were already critical of the state investigation. Commission 44 spokesman Khujamri Pirmamadov said state investigators were only interested in finding protesters, not the people responsible for killing Ziyobekov or those who ordered troops to fire on the protesters who assembled in Khorog the day he was killed.

Tajik authorities were also working on eliminating criticism from outside Tajikistan about the November violence in Khorog.

Amriddin Alovatshoyev (Credit: screengrab).

From Russia, Mixed Martial Arts fighter and GBAO native Chorshanbe Chorshanbiyev and GBAO local leader Amriddin Alovatshoyev posted criticisms of the government’s November actions in Khorog. Chorshanbiyev was then detained in Moscow in December for a speeding violation and deported to Tajikistan, where he was taken into custody, tried on spurious charges of calling for the violent overthrow of the Tajik government and, on May 13, sentenced to eight and a half years in prison.

Alovatshoyev disappeared in the Russian city of Beograd in January and reappeared in Tajikistan in February. Tajik state television aired footage of Alovatshoyev confessing to unspecified crimes on February 12. Alovatshoyev’s friends and relatives said the confession was made under duress On April 29, at a trial that lasted only several hours, Alovatshoyev was convicted of hostage-taking and other crimes and sentenced to 18 years in prison.

On May 14, local activists told officials about plans to hold a rally on May 16 to demand changes in the GBAO leadership and the release of all those still held in connection with the November unrest.

When people started to gather on May 16 and make their way to the Khorog city centre they were met with tear gas and rubber bullets. Soon after, troops started using live ammunition in Khorog and in Rushan district to the west, where unarmed residents had blocked the road to prevent reinforcements from reaching Khorog.

The incident in Rushan provided the pretext for starting the “anti-terrorism” operation and using armoured vehicles, helicopters, drones and snipers.

During this operation in GBAO, several informal leaders were killed, including Mamadbokir Mamadbokirov, Zoir Rajabov and Khursand Mazarov.

Ulfathonim Mamadshoyeva (Credit: Facebook).

Journalist Ulfathonim Mamadshoyeva, a native of GBAO who had covered Tajik politics going back to the civil war days, was arrested in May along with her former husband Kholbash Kholbashov. Both were shown on television confessing to organising the violence in GBAO. Details of their cases were declared secret and their lawyers were made to sign a non-disclosure agreement.

In August the state prosecutor called for Mamadshoyeva to be imprisoned for 25 years and Kholbashov for life for organising the violence in GBAO.

Khujamri Pirnazarov and Shaftolu Bekdavlatov (Credit: Social media).

On June 29, two members of Commission 44, Khujamri Pirnazarov and Shaftolu Bekdavlatov, were sentenced to 18 years in prison for organising an unsanctioned meeting. At the start of July, GBAO poet and camera operator Muyassar Sadonshoyev was sentenced to 11 years in prison and Khorog resident Iftihor Saidbekov to 10 years for cooperating with Commission 44.

Local Khorog cleric Muzaffar Davlatmirov was summoned by police for questioning on July 26. Davlatmirov had recently offered Friday prayers for some of the slain informal leaders. On August 3, it was reported that Davlatmirov was convicted of publicly calling on people to carry out extremist acts and sentenced to five years in prison.

Authorities resurrected the case of the killing of General Abdullo Nazarov in July 2012. Nazarov was a former UTO member and at the time of his death was the chairman of the Directorate of Tajikistan’s State Committee for National Security in GBAO. There were suspicions he was connected to narcotics trafficking and that was the reason he was stabbed to death. His murder sparked violence in GBAO that left at least 42 people dead. Two people were convicted of the killing in 2013.

On August 5, a GBAO court sentenced three people, all of whom were related to influential local leaders, to life imprisonment for involvement in Nazarov’s murder.

As of August 18, there were some 90 members of Commission 44 or GBAO civil activists in custody. Among them are Manuchehr Kholiknazarov, head of the Association of Pamir Lawyers, and attorney Faromuz Irgashev, two of only four registered lawyers for all of GBAO.

Several more GBAO activists from Russia have this year been detained and sent back to Tajikistan, including the Vazirbekov brothers who posted criticisms of the government’s security operation in GBAO. Both have Russian citizenship. The two flew from Yekaterinburg to Moscow on July 29 and vanished at Moscow’s Domodedevo Airport, reappearing in Tajikistan shortly after where they were shown in a video saying they had returned voluntarily.

Maksud Guyosov (Credit: Social media).

Another GBAO activist and blogger, Maksud Guyosov, was detained in Moscow on August 17.

Prince Aga Khan lV at a reception with Sharofat Mamadambarova, his former consul in Tajikistan (Credit: public domain).

On May 18, the Aga Khan released a statement calling on Pamiris to “remain calm, abide by the laws of the land, and reject any form of violence.

In late July there were reports that the government was looking to seize the schools the Aga Khan Development Fund (AKDN) has built and funded in GBAO and there was a surprise audit of the microfinance bank that the AKDN supported.

In August, the Khorog city park that was built by and belonged to the AKDN was confiscated and given to the state.

The president of the Ismaili Shiite Council of Tajikistan and former consul of the Aga Khan, Sharofat Mamadambarova, was questioned by Tajikistan’s security service on August 13 and 14.

Human Rights Watch, the European Union, the International Commission of Jurists, and others have called for the Tajik authorities to cease their campaign against the Pamiris, but to no avail.

A culture that has existed for centuries is now on the verge of extinction as the Tajik authorities purge Pamiri leaders and cut off the region from outside help.

Features

Minerals for security: can the US break China’s grip on the DRC?

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is offering the United States significant mining rights in exchange for military support.

Southeast Asia welcomes water festivals, but Myanmar’s celebrations damped by earthquake aftermath

Countries across Southeast Asia kicked off annual water festival celebrations on April 13, but in Myanmar, the holiday spirit was muted as the country continues to recover from a powerful earthquake that struck late last month

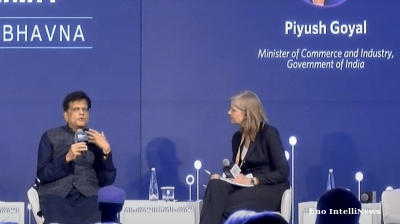

India eyes deeper trade ties with trusted economies

India is poised to significantly reshape the global trade landscape by expanding partnerships with trusted allies such as the US, Indian Commerce and Industry Minister Piyush Goyal said at the Carnegie India Global Technology Summit in New Delhi

PANNIER: Turkmenistan follows the rise and rise of Arkadag’s eldest daughter Oguljahan Atayeva

Rate of ascent appears to make her odds-on for speaker of parliament role.

_1744669887.png)