The world’s leaders meet in Munich this St Valentine’s day, and ending the war in Ukraine will be top of the agenda. Retired lieutenant general and US President Donald Trump’s special envoy to Ukraine Keith Kellogg will be the star guest; he is in the process of putting together a peace plan.

All the major actors in the conflict have softened their positions in the run-up the widely expected start of ceasefire negotiations. And as Kellogg has got into the weeds of the challenge he has backed away from his original suggestion of simply cutting off all aid to Ukraine if its president, Volodymyr Zelenskiy, refuses to come to the negotiating table, and flooding Ukraine with weapons if Russian President Vladimir Putin refuses to attend.

Trump has also become more realistic, extending his original boast that he would end the war in the “first 24 hours” of his term to calling for a deal to be cut in the first 100 days.

Kellogg’s goal at the Munich Security Conference (MSC) has also been diluted; originally it was reported that he would announce the details of the US peace plan at the conference. Now he is expected to consult with his European allies and report back to Trump, who will announce the plan himself, presumably on February 24, the third anniversary of the start of the war.

A lot of work needs to be done between now and then, as there are many thorny problems to resolve, but what exactly is on the table? And how much leverage do the Western allies have over Putin to bring about a lasting and “just” peace deal?

Land

The question of land will be one of the most difficult of all the discussions. Zelenskiy has held out for the return of all Ukraine’s occupied land, whereas Putin has repeatedly said that Kyiv will have to acknowledge the “realities on the ground”, which is widely interpreted to mean he wants to hold on to all the territory, some 20% of Ukraine, that the Armed Forces of Russia (AFR) have occupied since the start of the campaign.

Returning Crimea to Ukraine is clearly off the table. Even during the failed Istanbul peace deal in April 2022 it was agreed by both sides that the issue of sovereignty over Crimea would be kicked down the road for future governments to resolve. It also appears that Russia is not prepared to even discuss returning the “Novorossiya” land bridge that connects the Russian border at Rostov-on-Don with Crimea.

However, there is some room for compromise on territory. In leaked comments from the Kremlin, reported by Reuters at the end of last year, top Kremlin officials said there was “limited wiggle room” for land swaps concerning the four regions annexed by Russia in 2022 and land occupied by the AFR near Kharkiv.

Zelenskiy backed away from his maximalist position that all Russian troops have to leave Ukraine and return to the 1991 borders on February 11, suggesting that he is ready to swap Kyiv-held land in Russia's Kursk region captured during the Kursk incursion in August last year for Ukrainian territories.

"We will swap one territory for another," Zelenskiy said in an interview with The Guardian newspaper, without naming which territories he was talking about. "I don't know, we will see. But all our territories are important, there is no priority," he added.

But the ball is in play and the Kremlin came back the next day rejecting the idea of swaps completely. Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov said Russian forces would simply drive Ukrainian troops out of Kursk.

"This is impossible. Russia has never and will never discuss the topic of exchanging its territory," Peskov told reporters.

Peacekeepers

Another touchy subject is that of peacekeepers. The working model for most of the Western protagonists is that a ceasefire will be agreed but that Bankova (Ukraine’s equivalent of the Kremlin) will not get much land back and Russia will remain in control of most of the land it now occupies. A demilitarised zone (DMZ) will be then established that will be policed by Western troops.

This scenario was first suggested as part of the 12-point Chinese peace plan suggested on the first anniversary of the war and has since been championed by French President Emmanuel Macron.

However, the chances of this working are low. The Kremlin has said it is categorically against any Nato troops being stationed in Ukraine. Moreover, most of Ukraine’s Western allies remain very nervous about putting their forces in front of the AFR and others have questioned whether they even have the resources to do it.

The US won't send troops to Ukraine, US Defence Secretary Pete Hegseth said during a press conference on February 11. The US plans to review the deployment of its troops around the world, he explained, but has already decided it won’t send them to Ukraine. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz has also ruled out sending troops, while France and Britain remain vague on the proposal.

"The idea that establishing security guarantees for Ukraine and a ceasefire line along the current front line is all that’s needed is the West’s wishful thinking. We need to be preparing for a much longer and extraordinarily complex process that will take many months," senior German diplomat and former chairman of the Munich Security Conference Wolfgang Ischinger wrote in an opinion piece for Politico this week.

"Estimates of the number of troops required to effectively secure a 1,000-kilometre contact line vary from 50,000 to 200,000... Realistically, could Europe politically or militarily manage this, while the Bundeswehr is struggling to deploy a brigade [of 4,000 men] to Lithuania? Doubts can, therefore, be expressed as to whether Europe would even be capable of credibly securing a ceasefire with a large numbers of troops," Ischinger said.

The idea of the DMZ and peacekeepers appears to be a halfway measure where Nato allies step up to help improve Ukraine’s security but stop short of actually giving Kyiv Nato’s Article 5 collective defence guarantees.

That is unacceptable to Bankova. Zelenskiy has made it crystal clear that the key element of any ceasefire deal has to include genuine security guarantees for Ukraine by the Western community. A key part of the mooted negotiations with Russia actually starts with Zelenskiy’s negotiations with the Western leaders at the MCS, where he needs to persuade them to provide these guarantees, a deal that he is unlikely to close.

Minerals

The Western powers have all thrown themselves behind Ukraine, but the MSC meetings will be crucial for the outcome of the Russian negotiations, as despite the arms and billions of dollars in financial aid, Ukraine has still not secured the West’s full backing. Zelenskiy has repeatedly pleaded for accelerated Nato membership and been ignored. He has repeatedly pleaded for security deals and been ignored. What has been given instead is a string of “security assurances”, not guarantees. Even UK Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer, who was in Kyiv last month to sign off on the grandiose sounding “100-year partnership” between Kyiv and London, dodged the question when if asked if the deal included security guarantees. “Britian will do its part,” was all he would admit to.

Bankova got off to a rocky start in the first weeks of Trump’s presidency thanks to missing money, delayed arms deliveries and demand for mining deals dominating the agenda. However, Zelenskiy scored a major victory by dangling Ukraine’s considerable mineral resources under the US president’s nose, and he has taken the bait.

Ukraine has several trillion dollars’ worth of strategically important rare earth metals and other minerals, and Bankova is hoping to use the prospect of mining deals to make Washington commit to ensuring Ukraine’s security so US companies can safely exploit them.

Trump says that Ukraine has agreed to give the US access to $500bn of rare earth metals in exchange for weapons, the New York Post reported this week

"They have extremely valuable land in terms of rare earth minerals, oil and gas, etc. I want our money to be safe because we spend hundreds of billions in Ukraine. I told them: We have to get something. We can't keep paying this money," Trump said in an interview with Fox News.

Former British Prime Minister Boris Johnson believes that Trump is right to demand compensation for the US' enormous support, not only in the form of a rare earth metals deal but by unlocking the $300bn in frozen Russian assets. This money could be used to compensate for the damages caused by Russia to Ukraine, "provided that a significant portion of the funds returns to the US," he said this month.

But here too, Zelenskiy has also been clear that Ukraine will not give away the family silver for US money and arms alone. He wants joint ventures and investment, but most importantly, he has made it clear that any mining concession deals will be linked to security deals.

"We have mineral resources, but that does not mean that we are handing them over to anyone – even our strategic partners. It's about partnership. Invest your money. Bring in investments. Let's develop [the resources] together, let's generate revenue. Most importantly, this is about the security of the Western world and the European continent. These burglars – Russia and its allies – won't get their hands on everything," he said in an interview with Reuters.

Cold War missile deals

Once this preparatory work is done, there still remains the formidable task of dealing with the Kremlin, which has been playing hard ball from the beginning. Russia’s economy is cooling and the pain of running a war economy is making itself felt, but analysts say that Russia’s economy more robust than it appears and the Kremlin has enough money in reserve to continue to fight for at least two more years – and probably a lot longer. Putin doesn’t need to do a deal. But given the AFR advances have slowed to a crawl, despite the recent progress around the key logistics hub of Pokrovsk, many analysts believe he is ready to draw a line under the so-called “special military operation” and declare victory.

On the face of it, the West has little leverage over the Kremlin, but in reality there are two areas where fruitful talks can be held: security and sanctions relief.

Putin is obsessed with Russia’s security and began this war to ensure by conquest that Ukraine can never join Nato, which remains his top priority. But in addition to this, the Kremlin is equally keen to put back in place all the Cold War arms deal for the same reasons. Indeed, the start of serious tensions between Moscow and Washington can be dated back to George W Bush’s decision to unilaterally withdraw from the ABM treaty (Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty) – a key Cold War security deal.

Putin kicked off his relations with Biden by renewing the START missile treaty in January 2021 only a week after Biden had taken office. It was a landmark deal; the first of all the Cold War security deals to be renewed.

The Russian side was ebullient at the renewal of the START III deal and immediately suggested starting talks on renewing the INF treaty (Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty). But the champagne buzz of the START treaty success quickly wore off as relations rapidly deteriorated.

Offering to restart the talks to reactive these Cold War treaties would be pushing at an open door and is high on the Kremlin’s wish list. It’s a real bargaining chip that can be played in the upcoming talks.

While most of the Western reporting on the conflict circles around arms and money, or Nato and EU membership deals, the Russian side has been calling for arms control talks but garners little attention. Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov, who oversees US relations and arms control, and brokered the no-Nato for Ukraine diplomatic talks with the US in January 2022 before the war, said last week that the outlook for Russia-US talks on nuclear strategic stability did not look promising.

In January, Trump made some nebulous comments that he wanted to “work towards cutting nuclear arms,” but he has said nothing specific on the topic – comments that the Kremlin publicly welcomed. Trump also said that Putin told him he wanted to restart nuclear arms cuts talks as soon as possible, but until the two men meet there will be little progress on the initiative.

While the Kremlin is pushing for two-way Russo-US talks on ending the conflict in Ukraine, the US is asking for three-way arms talks that will include China. Moscow wants five-way arms talks that also include both Britain and France, as nuclear powers.

And the time is ripe for these talks, as the START III is due to expire on February 5, next year. It was significant that after renewing the deal with Biden, when the war started Russia “suspended” the deal, but pointedly did not withdraw, leaving the door open to resuscitating the agreement should tension ease. But with no active negotiations to extend or replace it, the treaty remains the last major nuclear arms control agreement between the world’s two largest nuclear powers.

If the START III is restarted then there is a long list of treaties that the Kremlin would like to revive and that gives the West ample leverage over the Kremlin to win numerous concessions, on Ukraine and more.

|

Main Cold War-era arms control treaties |

||||

|

Abbreviation |

Name |

Year Signed |

Description |

Status |

|

NPT |

Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons |

1968 |

Limits nuclear weapons spread; nuclear states commit to disarmament, non-nuclear states agree not to develop them. |

Active (Indefinitely extended in 1995) |

|

SALT I |

Strategic Arms Limitation Talks I |

1972 |

Capped ICBMs and SLBMs at 1972 levels to prevent an arms race. |

Expired (Replaced by later treaties) |

|

ABM Treaty |

Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty |

1972 |

Limited missile defence systems to prevent an arms race. |

Abandoned (US withdrew in 2002) |

|

SALT II |

Strategic Arms Limitation Talks II |

1979 |

Further limits on ICBMs, SLBMs and strategic bombers. |

Never ratified (Both sides adhered informally) |

|

INF Treaty |

Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty |

1987 |

Eliminated ground-launched ballistic and cruise missiles with ranges 500-5,500 km. |

Abandoned (US withdrew in 2019) |

|

START I |

Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty I |

1991 |

Reduced nuclear warheads and launchers significantly. |

Expired (Replaced by SORT and New START) |

|

START II |

Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty II |

1993 |

Banned multiple warheads (MIRVs) on ICBMs. |

Never entered into force (Russia withdrew in 2002) |

|

SORT |

Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty |

2002 |

Further reductions in US-Russia nuclear arsenals. |

Replaced (By New START in 2011) |

|

New START |

New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty |

2010 |

Limits US and Russian strategic nuclear warheads to 1,550 each. |

Active (Extended until 2026) |

|

Source: bne IntelliNews |

||||

Sanctions relief

Rolling back some of the thousands of sanctions on Russia is another strong leverage point Western diplomates have at their disposal and Ischinger for one thinks that it will be a necessary part of getting any concessions from Putin. The Kremlin has been lobbying hard against the sanctions regime since the first sanction were imposed on Russia in 2014 following the annexation of Crimea, but almost none of the sanctions have been repealed.

This conversation will be made easier as Europe in particular wakes up to the twin ugly truths that sanctions have not worked and they have backfired in a boomerang effect that is now doing more damage to the West than it is to Russia.

As reported by bne IntelliNews, oil sanctions have been a spent cannon and the technology sanctions have also largely failed; Russian imports of technology were down only 2% y/y in 2024 in value terms as partners in the so-called friendly countries have happily facilitated the transshipment of technology. A study by the EU last year found that intermediary trading companies have introduced up to 40 steps in a daisy chain of shell companies to hide the identity of the ultimate beneficiary of these exports, making them impossible to track. The sanctions regime is a game of whack-a-mole that the West is not winning.

There are a number of sanctions that are completely ineffective that can be easily dropped without making much material difference to the regime, which is having an effect and ultimately will contribute to the Russian stagflation that is widely anticipated by many economists in the coming years.

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban called again for sanctions on Russian energy to be lifted on February 12, as the countries of Central Europe remain dependent on the import of Russian oil and gas.

But others in Europe remain implacable Russian foes, led by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and EU foreign policy chief and Estonian Prime Minister Kaja Kallas, who are no mood for compromise and would like to see Russia’s economy destroyed.

There is a choice between sticking to absolute or relative sanctions. As bne IntelliNews argued elsewhere, it is not necessary to completely ban the import of Russian fossil fuels if the goal is limited to breaking Europe’s dependency on cheap Russian energy. It is only necessary to reduce those imports to the point where Russian gas can be replaced by something like US LNG imports, or around 15% of the energy mix – a level that has already been achieved. But for players like von der Leyen, the goal is to totally end any reliance on Russia's raw materials or energy and see the Russian state shrivel.

The US sanctions on imports of Russian uranium is another example. Uranium is the new gas, as Russia remains the leading global producer of enriched uranium. The US has banned imports, but as it makes a fraction of what it needs to run its own fleet of nuclear power plants (NPPs) it has introduced a system of exemptions in parallel that run until 2028, when it hopes to become self-sufficient in yellow cake uranium production.

Thanks to the boomerang effect of sanctions, relieving many of the restrictions would benefit Europe far more than they would Russia, by lowering costs and shortening supply lines that would help the EU improve its competitiveness.

The alternative is to greatly increase sanctions and tighten the more effective ones on Russia’s shadow fleet, or the banking sanctions.

Trump’s special envoy Kellogg rated Russia's pain resulting from current sanctions at "only a three" on a ten-point scale last week. “You can’t get out of this war just by killing,” he said. He added that Russia is prepared for a war of attrition, so the pressure cannot be simply military. "You have to apply economic, diplomatic and military pressure..." he explained. But he also added both sides, Kellogg again noted, will “have to make concessions.”

Sanctions relief is not a given, as since December last year, when the US introduced the so-called strangulation sanctions that target specific products and companies, the US has had a lot more success at inflicting more than a “three” on Russia. In addition, the US financial sanctions introduced last year appear to be working much better than the Biden administration’s harshest yet oil sanctions imposed in December. They have also proved to be surprisingly effective, disrupting Russia's oil deliveries to partners like India.

Trump has threatened to impose extreme duties on Russia if Putin proves to be unwilling to negotiate, but analysts point out that with only some $3bn of mutual trade, this is largely an empty threat. However, scaling up the financial and oil sanctions is an option. The question remains if Russia can find a workaround. And as long as it has help from its partners in the BRICS+ it seems likely that it will be able to continue to avoid them. But the bottom line is that Putin is not afraid of more sanctions and will only be determined to find new dodges, so the threat of stepping up sanctions is not a leverage point in the upcoming talks.

Features

Minerals for security: can the US break China’s grip on the DRC?

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is offering the United States significant mining rights in exchange for military support.

Southeast Asia welcomes water festivals, but Myanmar’s celebrations damped by earthquake aftermath

Countries across Southeast Asia kicked off annual water festival celebrations on April 13, but in Myanmar, the holiday spirit was muted as the country continues to recover from a powerful earthquake that struck late last month

India eyes deeper trade ties with trusted economies

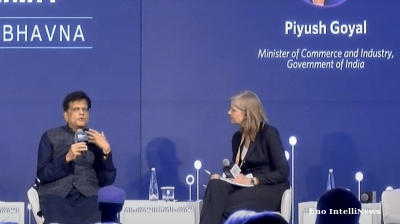

India is poised to significantly reshape the global trade landscape by expanding partnerships with trusted allies such as the US, Indian Commerce and Industry Minister Piyush Goyal said at the Carnegie India Global Technology Summit in New Delhi

PANNIER: Turkmenistan follows the rise and rise of Arkadag’s eldest daughter Oguljahan Atayeva

Rate of ascent appears to make her odds-on for speaker of parliament role.

_1744669887.png)